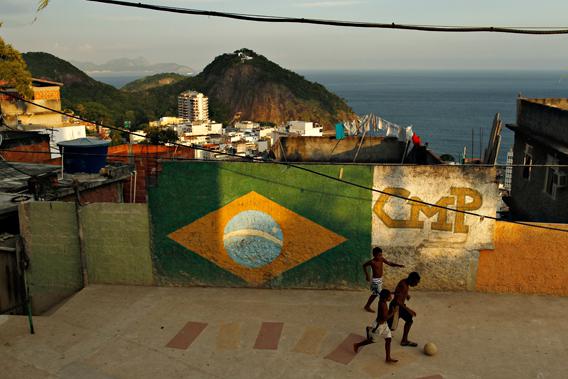

RIO DE JANEIRO—In the sunshine, this is a city of bright colors, fast movement, soaring vistas. But in the rain—and it can rain very hard indeed—the colors fade to grey, the traffic slows to a halt, and the vistas disappear into the fog. In the favelas, the tin-roofed slums that cover the hills just behind the famous beaches, the steep walkways turn slippery and slick.

Which is why it was so surprising, on a recent rainy day, to climb up into the favela that spreads out behind Copacabana and come upon Bar do David, a famous favela eatery, as well as David himself. We didn’t exactly get dry while chatting with David and eating his seafood croquettes, but we did hear about the multiple awards he has won for “favela cuisine” and read the reviews framed on the walls. He’s been in business three years, he said. “And if I’d been here four years, I would have won an Oscar by now.” Next door, the news blared from a large flat-screen TV.

The economics of favela life are complex, not to say mysterious: Then next day, I met an articulate teenager with a fifth-grade education and brand-new sneakers. But then, of all the nations misleadingly known as “developing” economies, Brazil might be the one that most emphatically defies stereotypes and expectations. Once, the world imagined that international trade meant that people in poorer countries would provide “hands for Western brains,” as the writer Adrian Wooldridge put it. Instead, Brazil is one of several “developing” countries that have become innovators in their own right, producing not only entrepreneurial businesses such as Bar do David but also multinational companies such as the plane manufacturer Embraer or Natura, which makes a fortune out of organic perfumes and cosmetics. The country is an international leader in the production of biofuels and the use of ethanol in cars; Brazilians tweet more than any other nationality except Americans.

Past Brazilian governments have also been social innovators, creating, for example, the much-copied bolsa familia, a program that, among other things, offers very poor families benefits in exchange for keeping their children in school. And all of this takes place in a country where power changes hands regularly, and relatively peacefully, after democratic elections conducted under the watchful eye of a free press.

There are, of course, many things that nobody likes about Brazil: red tape on a Dickensian scale (re-read Bleak House for a primer on the workings of court systems in badly managed capitalist societies), corruption, nepotism, and inequality. But there are also plenty of things worth admiring in this innovative democracy. A group of Egyptians recently asked to come and learn how Brazilians ended their military dictatorship. And Brazil’s anti-poverty programs are being studied in South Africa—a fact that surprises Brazilians. This seems odd: The adherents of Islamic fundamentalism aren’t shy about promoting their beliefs. Nor are Russian, Chinese, or Venezuelan authoritarians. Americans famously try to encourage democracy, sometimes even with good results. So why doesn’t Brazil?

When I asked that question in Rio, I got some odd answers. “We like being nonaligned, even though there isn’t anything to be non-aligned from anymore,” one person told me. “Brazil wants to be first in the Third World, not last in the first world,” said another. Brazilians, I was told, don’t want to be thought of as a “Western democracy” or as a rich country; they don’t want to be allied in any sense to the United States or Europe; and they don’t like the fact that the world is dominated by American values and institutions. Asked whether the Brazilians preferred a world dominated by Chinese values and institutions, a foreign policy scholar shook her head in horror. No, no, of course not, she said, before agreeing that maybe the Brazilian worldview wasn’t entirely consistent. Perhaps the hostility toward Western democratic clubs is understandable, given that Brazil’s current political leadership descends mostly from the anti-American left. But as I passed armies of headphoned, lycra-clad joggers on the beach, it struck me as weirdly out of date.

It’s also self-defeating. As an old joke has it, Brazil has been the “country of the future” for at least a century. But perhaps Brazil’s failure to “arrive” as a new power on the world scene comes from Brazilians’ failure to recognize their potential to inspire others. There are worse paths to follow than that of the “Brazilian model,” despite its flaws, just as there are worse places to live than Rio’s favelas. If only Brazilians knew it.