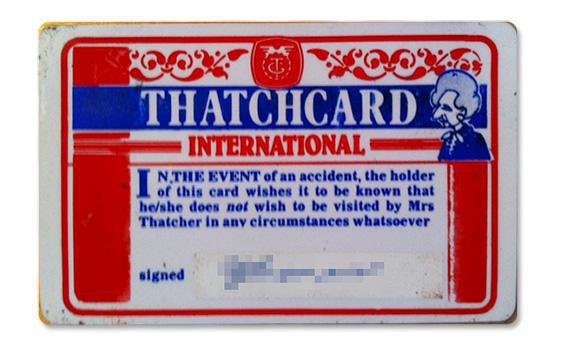

I was a card-carrying member of a Thatcher-hating society. No, really, here’s my card.

Provided by June Thomas

I don’t remember where I got it—a Marxism Today conference, perhaps (kids, that’s what we did for fun in the late 1970s)—but I have a strong recollection of the mood of those times. It felt like Britain was falling apart. Every week there seemed to be an IRA terrorist attack or a transportation disaster—a devastating fire in a train station, the sinking of a pleasure boat in the Thames. Whatever the cause, as soon as the surviving victims were bandaged up and rendered presentable, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher would show up at the hospital for a photo op. This filled Brits like me with a combination of rage and terror. Thus the Thatchcard: “In the event of an accident, the holder of this card wishes it to be known that he/she does not wish to be visited by Mrs. Thatcher in any circumstances whatsoever.”

I know how churlish that may sound now. I carried around a ridiculous piece of plastic announcing that if one of the leaders of the free world took the time to visit my sickbed, I wished her turned away. (To my shame, I’m pretty sure that at the time I didn’t even carry an organ donor card, which the Thatchcard was modeled on.) In my defense, in that era Britain was suffused with such intense Thatcher-hatred that the enmity Obama truthers express for the president seems like a love affair by comparison.

I’d spent my elementary school years yelling “Thatcher, Thatcher, milk snatcher,” because I was one of the kids deprived when, as education secretary, she abolished free school milk. Until that policy went into effect, I’d spent every morning complaining bitterly about having to drink those odd little bottles of curdling room-temperature milk—at least that’s how it was served in my school—but that didn’t stop me from protesting the reform. And from the time I was in high school until I left Britain not long after I graduated from university, a sure-fire way—usually the only way—to perk up a protest was to start the chant to which Britons of a certain age have a Pavlovian response: “Maggie, Maggie, Maggie!, Out, out, out!”

Check out Elvis Costello’s performance of “Tramp the Dirt Down,” a song in which he tells Thatcher: “I’d like to live/ Long enough to savor/ That when they finally put you in the ground/ I’ll stand on your grave and tramp the dirt down.”

Why was Thatcher such a hated figure? Yes, it was about her policies—privatization, the selling off of public housing, her wars against Argentina in the Falklands and against the miners and the working class in Britain—but there was something else at work. On some level she was hated because she was a woman. Between men who hated themselves for responding to Thatcher’s stern, dominatrix-like scolding (watch “You turn if you want to; the lady’s not for turning” and tell me you don’t get chills) and women who wondered why our breakthrough female politician had to be a woman like her (though we surely knew that only an Iron Lady could have smashed the mold of British politics), the fact that Thatcher was female complicated things. Even her name was a hostage to ideology: Those on the left always used a condescending diminutive—Maggie Thatcher—while her devotees on the right used the honorific Mrs. Thatcher.

But in the typical British way, I have always believed that it was her slippery position in Britain’s rigid class system that ramped up the levels of loathing. She grew up the daughter of a Midlands grocer in what the Guardian’s Michael White called “the respectable working class.” Although she famously learned to speak in a posh accent as she climbed the political ladder, she grew up in a house without an indoor bathroom. Although throwing in her lot with the Conservative Party made her a traitor to her own class, the Tories apparently celebrated their colleague’s upward mobility—they did, after all, make her their leader, even if she was never quite “one of them.” (In 1983, she reverted to the dialect of her youth when she called a member of the opposition Labour Party “frit”—frightened—at the prospect of an election. In the words of the BBC, this was “a rare loss of composure from Mrs Thatcher.” The slip apparently haunted her.)

These days, with the passing of time, the fading of memory, and the spirit of de mortuis nil nisi bonum, I feel guilty about all that hate. This morning when I heard the news, after decades of dutifully shifting the darned thing from wallet to wallet, I finally retired the Thatchcard.