West of China, north of Afghanistan, south of Russia, and firmly in the middle of nowhere for most Americans until Friday, lies a small, beautiful country called Kyrgyzstan. This land is so seemingly remote and consonant-heavy that our own secretary of state recently referred to a nonexistent, composite Central Asian entity called “Kyrzakhstan.” Kyrgyzstan hosts a major American military base essential for the Afghan war, but those are just details.

The gaffe capped a long history of jokes and satire that have come to define the fragile new states of post-Soviet Central Asia in many Western minds, if those minds had any room for Central Asia at all. No one captured the zeitgeist better than Gary Shteyngart in his novel Absurdistan, a wild romp through a fictional, though at times all too real, land of tin-pot dictators, bizarre ethnic divisions, greedy foreigners, and other strange characters.

To the list of characters to emerge from Central Asia onto the American psyche we now must add the Tsarnaev brothers, the sadly nonfictional ethnic Chechens who spent parts of their childhoods in Kyrgyzstan before eventually reaching Boston to set off bombs at the crowded marathon finish line. A rebellious people, long at odds with Russian colonizers, the Chechens were exiled en masse to Central Asia in 1944. The descendants of those exiles formed tight-knit diasporas across the region and watched from afar as their ancestral homeland, still part of the Russian Federation, got bulldozed in a separatist war in the 1990s, to be later rebuilt into a police statelet under Ramzan Kadyrov, a thuggish, Instagram-loving young vassal installed by Moscow.

We may never know whether the generational history of banishment, exile, and immigration, of watching their ancestral land get butchered in a dumb war, could have somehow contributed to the sickness brewing in the minds of the Tsarnaev brothers. Just like we’ll never know what could compel Adam Lanza, a born-and-bred American kid who never knew banishment, exile, or immigration and who never watched anything dear to him destroyed in a dumb war wake up from suburban slumber one day and commit mass murder of children with a semi-automatic weapon.

But our minds need a narrative to stitch the world whole, if not to explain things then to at least line them up in a row so that we can pretend that such sequencing can give us clues to causes and effects. And the Tsarnaevs’ family meanderings, before ending so bloodily in America, took place against a particularly rich backdrop of some of the most unsettled and unsettling places of Caucasus and Central Asia.

During World War II, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin relied on tendentious evidence amplified by his own paranoia to accuse some ethnic groups in the Soviet Union of collaborating with the Nazis. He punished the imagined or exaggerated crime of treason with the very real crime of de-facto genocide by uprooting entire peoples from their homelands and sending them off to Siberia and Central Asia. Chechens, Ingush, ethnic Germans, and Meskhetian Turks were the biggest casualties of these mass deportations that took place in typhoid-infested trains where many of the exiles died. Those who survived had to start over in the freezing, inhospitable Central Asian steppes with little more than the clothes on their backs.

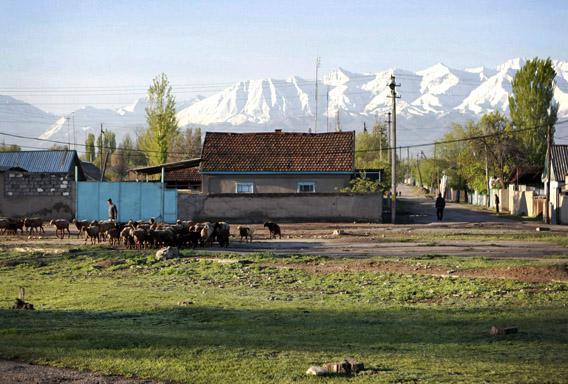

In Kyrgyzstan these days, you cannot walk very far without bumping into the descendants of those deportees. In Osh, in southern Kyrgyzstan, I met an ethnically German Russian Orthodox priest, whose great-grandmother got deported to neighboring Kazakhstan, her ethnicity proof enough of high treason. In a village outside the capital Bishkek, I met a Turkish farmer who answered my stupid question of how he got to Kyrgyzstan with a single word: “Stalin.” Central Asia’s Chechens have similar stories, welded to a single winter night at the tail end of World War II, the night they or their ancestors were rounded up and loaded onto trains.

In Central Asia, the Chechen diaspora produced some noteworthy characters. Among the most famous Kyrgyz Chechens is Makhmud Esambayev, a legendary Soviet ballet dancer and choreographer. Another big-name Central Asian Chechen is Dzhokhar Dudayev, a former president of Chechnya whom the Russians assassinated by a missile homing in on his satellite-phone signal. The surviving Tsarnaev brother shares his first name. Just a week before the Boston brothers forever stole the mantle of being the most infamous Kyrgyz Chechens, another notorious Chechen dominated the country’s headlines. Aziz Batukayev, a feared mafia boss with the exalted title “thief within the code,” negotiated a highly suspicious early release from Kyrgyz prison that must have been greased by more than goodwill. He headed straight to the airport, where a chartered aircraft was waiting to whisk him to Chechnya.

During the first decade of its independence from Moscow, Kyrgyzstan was sometimes referred to, improbably, as the Switzerland of the East, because of its flirtation with democracy and a market economy, both an anathema to the wider authoritarian neighborhood. The Tsarnaev family left Kyrgyzstan in 2002, before the country embarked on its unlikely experiment. By 2005, the Switzerland-of-the-East president had become thoroughly corrupt, and in March of that year, an Arab Spring–style revolution chased him out of office. The person who took his place promised democratic renewal, but his excesses quickly surpassed those of the previous regime. Government opponents began to suffer suspicious deaths, falling out of windows or getting strangled. In 2010, five years after their first revolution, the Kyrgyz people stormed the presidential palace again, forcing the president to flee the country. A small civil war followed.

By then the Tsarnaevs were already living in America. Following the Boston bombings, countries that had anything to do with them quickly disowned the brothers. Ramzan Kadyrov, the thuggish Chechen despot, said the pair grew up in America and the roots of their evil should be sought there. He’s not wrong. Kyrgyzstan’s intelligence service, noting that the brothers departed the country aged 15 and 8, said it considers it “inappropriate to connect them to Kyrgyzstan.” Even the Czech Republic’s ambassador to the United States, whose country’s connection to Chechnya is purely orthographic, felt compelled to note that the Czech Republic and Chechnya are “two very different entities.”

And so the itinerant brothers found their final shelter in America, perhaps the only place where they could have truly felt at home, and we are left to wonder why they didn’t.

Read more on Slate about the Boston Marathon bombing.