This article is excerpted from William J. Dobson’s book, The Dictator’s Learning Curve: Inside the Global Battle for Democracy.

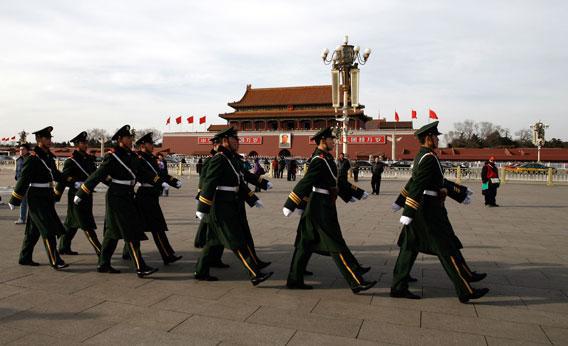

Today is June 4, the 23rd anniversary of the Chinese government’s brutal massacre of its own citizens in Tiananmen Square. That means, like all the June 4s since 1989, that today Chinese security forces are on high alert, watchful for anyone who would attempt to use this day as an opportunity to make a political statement or remind people of the night Chinese soldiers fired on fleeing students in the streets near Tiananmen. But, as special a day as June 4 may be for those Chinese who remember what happened, it is not the only day the regime sits on edge.

The longer the Chinese Communist Party stays in power, the more politically sensitive anniversaries the regime accumulates. The calendar has become littered with dates that remind people of the regime’s crimes or serve as potential flash points. A quick rundown of the Chinese political calendar would include March 10 (the anniversary of the 1959 Tibetan Uprising), May 4 (anniversary of the 1919 May 4 Movement), June 4 (the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre), July 5 (the 2009 suppression of Muslims in Xinjiang), July 22 (the 1999 crackdown on the Falun Gong movement), and Oct. 1 (the 1949 founding of the People’s Republic). Any of these dates are times when the regime must be on the lookout for those who might try to rally people against the Communist Party. Indeed, the fear was great enough in 2009—when many of these dates had important anniversaries—that the party reportedly established a special high-level task force called the 6521 Group. (The numbers 6521 referred to the 60th anniversary of the People’s Republic, the 50th anniversary of the Tibetan Uprising, the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre, and the 10th anniversary of the Falun Gong crackdown.)

Last year, in February, I was in China when the regime appeared to be fretting that a new challenge to its authority might be amassing. A group, identifying itself only as the “organizers of China Jasmine Rallies,” had posted a message on Boxun, a Chinese-language news site based in the United States. No one knew who had issued the call. It read, “We call upon each Chinese person who has a dream for China to bravely come out to take an afternoon stroll at two o’clock on Sundays to look around. Each person who joins will make clear to the Chinese ruling party that if it does not fight corruption, if the government does not accept their supervision, the Chinese people will not have the patience to wait any longer.” The calls for a “Jasmine Revolution”—borrowing the name from the revolution in Tunisia a month earlier—quickly spread to other web sites and on the Chinese equivalent of Twitter. The group behind the message identified specific locations in Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and more than a dozen other major cities around the country where people were to come out for a “stroll.” People were asked to assemble at 2 p.m.

The designated spot in Beijing was a two-story McDonald’s in Wangfujing, an upscale shopping area not far from the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square. On the second Sunday of protests, a friend and I arrived at the McDonald’s more than an hour before the appointed time. If you did not already know that the revolutions in the Middle East had frayed the nerves of the country’s leadership, visiting Wangfujing that afternoon made it abundantly clear. Police and security officers were everywhere. Hundreds of blue-uniformed police officers had been deployed to just one block. Some were patrolling up and down the street; others stood on the sidewalk or in doorways, staring at each and every person as they walked past. Security volunteers, wearing red armbands, supplemented their numbers. And, adding to the show of force, plainclothes officers mixed among the people; the number of undercover police was overwhelming. At moments, in the crowds, almost every third person seemed to have an earpiece and wire coming out from under his shirt.

We ducked into the McDonald’s. Like on any day, the fast-food restaurant was busy and filled with customers. Ten or twenty years ago, as a foreigner traveling in China, you grew accustomed to having Chinese gawk at you for no other reason than you were foreign. That is seldom the case today, especially in cosmopolitan places like Beijing. But on this particular day, as soon as we walked inside, most of the patrons stared at us across their trays of food. A fair number of them had crew cuts and earpieces, too.

We took our burgers and fries to the second-floor to kill some time. After we had been sitting for a few minutes, two bulky, stern-looking men sat at the table next to us. They weren’t wearing uniforms or earpieces, but they were clearly with the Public Security Bureau, as it is called in China. Their boots were military-issue and they ate their burgers in silence.

We remained as long as we could, but after finishing our meals it became awkward to sit next to the security officers. Plus, it was getting close to 2 p.m., so we decided to return to the street. As we approached the stairs, I noticed five thuggish-looking guys at a table at the top of the landing, staring out across the restaurant, expressionless. Halfway down the stairs, I stopped and looked back up. One of the men had pulled out a small video camera and was taping us exiting the restaurant. He saw me catch him filming and smiled.

Back outside, the number of people milling about was growing. It was impossible to say whether the people walking up and down the street had come for the protest or were simply Sunday shoppers. That was the brilliance of the tactic the organizers had chosen. In places as politically restrictive as China, people going to the streets with banners or bullhorns to challenge the ruling regime do not last long. A frontal attack on the Chinese Communist Party is almost never tolerated; such protestors are hauled away to be imprisoned, “re-educated,” or never heard from again. In contrast, the call for people to “go for a stroll” struck the balance of putting the regime on edge without asking people to take an unnecessary risk. Indeed, it is a tactic with some history. In 1980, members of Poland’s Solidarity movement learned that the Communist regime intended to fire on them when they went on a planned strike in the Gdansk shipyards. So rather than begin with a ploy that might provoke the police and snuff out the burgeoning movement, they took the less confrontational approach of strolling in large numbers in public places. As in Poland, Chinese authorities were being put in the awkward position of trying to prevent a demonstration that wasn’t even happening.

The afternoon took on a surreal quality as more and more people turned up, walking slowly in a loop on the block or two near the McDonald’s. It is hard to characterize the crowd as a whole. The people were neither predominantly young nor old; no one stood out. Some were stylishly dressed; others looked like everyday Beijingers. By far, the regime’s police officers and security personnel were the largest group there. The second largest contingent was probably the throng of foreign journalists who had shown up, curious to see if anything would happen. But the sidewalks began to clog as the crowds of Chinese steadily grew. Many, even most, of these people may have been unaware of the call for a Middle East-inspired protest. Just as likely, they were curious about why so many police officers had been deployed to this high-end shopping district, and as people stopped to stare, it had the effect of making more people do the same.

By 2:30 p.m., the Chinese authorities began to demonstrate their expertise in crowd-control techniques. Ahead of the day’s event, the authorities had narrowed the public space in front of the McDonald’s by erecting wooden barricades that read “Street Repair.” (Of course, there was no construction evident.) No one was allowed to stop and gape for long. Police kept people moving, channeling the crowd in one direction, and then redirecting it in another. A large sanitation vehicle began to spray the street with high-pressure jets of water; it circled back and forth, cleaning the same street corner again and again, preventing anyone from lingering. Police officers with German shepherds and Rottweilers ensured that people stayed on the sidewalks. Roads leading to the intersection were roped off, preventing more crowds from joining us. An exit from a mall near the McDonald’s was closed. I kept making loops up and down the block: down one side, then across the street, and up the other. I would see the same people again and again, as the security officers moved us as if in some elaborate, choreographed ballet. Similar scenes reportedly occurred in Shanghai and other cities, where the police presence was equally impressive. In Urumqi, the capital of restive Xinjiang province, almost no citizens were allowed near the protest site.

The regime’s heavy-handed response revealed its own worries that the protests ripping through authoritarian regimes in North Africa and the Middle East could somehow find their way to China. There was no hint of revolution in the air in February 2011, but China’s leaders intended to take no chances. Even before the first Sunday stroll, dozens of dissidents and human rights lawyers were rounded up and pre-emptively detained. Some were held under house arrest; others simply disappeared for weeks. Chinese President Hu Jintao called together provincial, ministerial, and top military leaders for a special study session at the Central Party School in Beijing on how the regime should tailor its tools for “social management.” All the members of the Politburo Standing Committee—the nine most powerful men in China—attended Hu’s speech at the meeting, which underlined the importance of tightening the regime’s control of information. The Chinese characters for jasmine had already been blocked from the Internet. Peoples’ ability to send text messages to multiple recipients was suspended. Boxun, the Chinese-language website, came under attack and was temporarily shutdown. In a more conciliatory gesture, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao held a Sunday morning Internet chat in which he pledged to sideline corrupt officials, rein in mounting inflation, and ensure that the fruit of China’s economic growth was more evenly distributed.

But when an authoritarian regime is rattled and insecure, it has a tendency to extend its ordinary prohibitions even further. In early 2011, China was no different. The organizers behind the anonymous protests had been shrewd to latch onto the “Jasmine Revolution” label. The name obviously linked their effort to the Tunisian revolution, where the rebellions against Arab autocrats had begun. But the jasmine flower has deep resonance and symbolism in Chinese culture as well. The white flower appears frequently in Chinese paintings dating back hundreds of years. Almost immediately, renditions of “Mo Li Hua,” a popular ode to the jasmine flower from the 18th century, were deleted from websites. These included videos of Hu and his predecessor, former Chinese President Jiang Zemin, belting out the tune. (The folk song is so popular it was played during the medal ceremonies at the 2008 Beijing Olympics and at the opening ceremony of the 2010 Shanghai Expo.) Authorities followed by imposing a ban on jasmines on Beijing florists and in the city’s flower markets. Vendors were told to report people showing interest in buying the now controversial flower. In such a politically charged environment, the mere mention of “jasmines” became something to be avoided. In my meetings with party officials, no one would even say the word, preferring to refer to “that flower.”

Outside China, the People’s Republic is perceived as an economic powerhouse. And rightly so: The Chinese government’s economic performance since beginning reforms in 1978 is nothing short of spectacular. For 30 years, China has averaged more than 9 percent growth. At that pace, the Chinese economy has doubled in size every eight years. In 2010, it surpassed Japan as the world’s second-largest economy, a position Japan had held for much of the last four decades. Most economists expect China to surpass the United States as the world’s largest economy in the next 15 to 20 years. When Deng Xiaoping first launched the country’s reform era, China’s economy was less than 8 percent the size of the U.S. economy.

The significance of this extraordinary growth has been greatest for the people of China themselves. More than 300 million Chinese citizens—essentially the population of the United States—have risen from absolute poverty in this time. Today, China has a vibrant middle-class that makes its home in new urban boomtowns. The country can also boast a burgeoning class of wealthy and superrich elites. In 2010, the value of IPOs on Chinese stock markets was more than three times greater than those in New York. China has more than 800,000 millionaires and 65 billionaires, second only to the United States. In the summer of 2011, as the Standard & Poor’s rating agency was downgrading the creditworthiness of the U.S. government, the Communist country’s leaders—after a fair amount of gloating—expressed their faith in American capitalism. After all, as the largest foreign lender to the United States, China wants to protect its investment. (At the time, the U.S. government owed each Chinese citizen roughly $900—and rising.) To be sure, the Chinese economy has no shortage of risks and frailties, including rising inflation, a housing bubble, and institutionalized corruption. Nevertheless, for a country of 1.3 billion people, the Chinese Communist Party has led the most astonishing economic achievement of not just our generation, but any generation.

Yet, for all the superlatives and accomplishments, China hardly behaves like a confident power. Its image as a modern economic colossus obscures an equally true picture of an insecure regime constantly tamping down the forces it believes could lead to its destruction. Indeed, it is fair to say that no regime thinks more about its own demise than the Chinese Communist Party. China’s leaders, judging by their actions, policies, and statements, are fixated on the weaknesses that run through their political system. It is an insecurity that manifests itself in ways that can in one instance be trivial and in another terrifying. Internationally, a representative of China is now one of the most important people in the room, whether the setting is the G20, the World Bank, or Davos. But domestically it is a regime that mobilizes thousands of police because someone writes on a foreign website that Chinese citizens should “go for a stroll.”

Thus, today, two statements are true. The Chinese Communist Party is the largest, wealthiest, and most powerful political organization in the world. And it is also afraid of a flower.