A small group of colonies manages to break away from a large empire in the closing years of the 18th century. The resulting state would probably be not much more than the Chile of the Northeast—a long littoral ribbon between the mountains and the ocean—if it were not for the imperial rivalries that allow for the rapid growth of the new republic’s influence. When one of the rival empires gets into serious financial trouble, it sells the new republic enough territory to double its size, at a bargain basement price. This new territory, rich in all aspects, also gives access to a vast internal basin of navigable rivers. On exploration, this system eventually gives place to the coast of another ocean, and to lands that contain vast reserves of such desirable minerals as gold. Another immense tract of this, today known as Alaska, is almost casually sold to the envoy of the new republic, along with tremendous deposits of what will one day be known as “oil.” …

So yes, I suppose you could say that the United States had some kind of luck, or force, or destiny, on its side. There were certainly those, even among its most secular founding fathers, who felt that more than ordinary realpolitik was involved. Thomas Paine for example was taken by the idea of a new Garden of Eden and a fresh start, and it was his words that were later to be quoted by Ronald Reagan when he said that he thought humanity had found the power to begin the world over again.

Of course, with any Eden there must be a serpent and an original sin. In the American case at least, Thomas Paine knew quite clearly what it was. The vile stain of slavery was present at every point, just as the awful profitability of cotton, and the easy availability of unpaid human labor from the African trade, corrupted the ideals of the new republic from the very first. In the end, the reckoning for this historic crime led to a war in which much of the ill-gotten wealth was squandered. On the other hand, that same civil war led to the triumph of capitalism and the expansionist state, with the new republic soon becoming an empire in all but name in the Philippines, Cuba, Haiti, and Puerto Rico.

Along the way, it was inevitable that politicians like Albert Beveridge would proclaim the idea of “manifest destiny” and the natural right of Americans to a dominant role in the world. It is the self-confidence involved in this idea—or rather the loss of it—that some people think should be the subject of the current presidential campaign. A candidate can expect to be ambushed and asked to affirm or deny the special position of the United States as an exemplary city on a hill, “shining” as a beacon to the less fortunate. On a slightly lower element of the scale, people answering polls have recently been asked whether they agree with this statement: “Our people are not perfect but our culture is superior to others.” The most recent polling on the latter point shows less than half of Americans in favor of the slightly tepid proposition, though it’s not obvious whether the perfection or the superiority is being voted on the most.

Especially to the extent that it starts to look like a loyalty oath, I think that the underlying question here should be dismissed as rash or stupid or both. Is the United States “chosen by God and commissioned by history to be a model to the world”? Anybody claiming to have the answer to that question—as George W. Bush once seemed to do—would be a fool. For a start, what would be his sources of information? And how good a historian would he be? In the long view, very few of the survivors of the Roman Empire would have predicted that the inhabitants of the frozen and backward British Isles would be among the next builders of a global system, but so it proved. And there was no question that the British or English, especially the Protestant fundamentalist ones, believed that they had God on their side. In fact, I know of no European state that doesn’t have some kind of national myth to the same effect. The problem, as everybody knows, is that not all these myths can be simultaneously right.

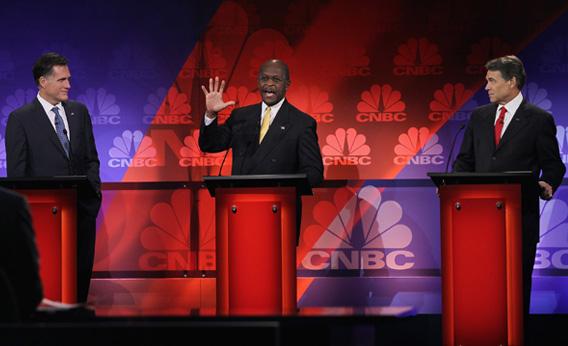

Long-term ideas of “destiny” are not easily assimilated to shorter-term glooms about the loss of American power and prestige. It’s a strange fact, but in the present political season it is the American right that seems to harbor the most skepticism about American power. I personally find this odd: Yet again the United States has managed to get itself largely on the right side of a massive historical shift—the Arab Spring—which it had not “read” very well the first time round. And yet, most of the remarks made by seekers of the Republican nomination have been sour or grudging.

I remember Bernard-Henri Levy saying, in the early stages of the Iraq war that he opposed, that America had been essentially in the right about combating fascism and Nazism, and essentially right about opposing and outlasting the various forms of Communism, and that all else was pretty much commentary or, as one might say, merde de taureau. Something of the sort seems to apply in the present case, both in recent developments in Burma and Vietnam as well as in Libya and Syria. The crowds have a tendency to be glad that there is an American superpower, if only to balance the cynical powers of Moscow and Beijing. Perhaps if it were not for President Obama being in the White House, our right wing would be quicker to see and appreciate this point.

The ancients taught us to fear “hubris,” and the Bible teaches the sin of pride. I am always amazed that American conservatives are not more suspicious of self-proclaimed historical uniqueness. But proclaim it they do, as if trying to reassure themselves against the blasts of what looks like a very bad season.