The vote-counting process in the 19th century was complex, unstandardized, and vulnerable to corruption. Counting practices varied from precinct to precinct, and a lot of alcohol was involved.

In the early part of the century, some Americans voted in public, using a method called viva voce (or “by voice”). This was a holdover from a Colonial practice, in which property owners (the only voters of the time) attended meetings and voted by a show of hands. In the 19th-century viva voce system, people went to local polling places and swore an oath that they were voting in good faith. Then, out loud and in front of anyone who cared to cluster around observing, the voter told the election judges his choices. The counting took place by hand; judges entered voter choices in poll books, keeping running totals of numbers of votes for each candidate. There were no paper ballots to tally.

In other locations, 19th-century voters used paper ballots issued by parties—a practice that became increasingly common as the century went on. Voters brought their own ballots to the polls, and although they could write their choices on pieces of paper, parties found that providing printed ballots with the names of their candidates was a convenience that nudged voters toward voting “straight ticket.” Parties printed their tickets on colored paper, and the ballots went into glass boxes, so that anyone observing a vote could clearly see which party a voter had chosen. The atmosphere at the polls was raucous, and party members lobbied for voters’ favor right up to the moment when they arrived at the ballot box.

As voters arrived at polling stations, election judges noted their names in poll books. At the end of the day, the tally of names was supposed to match up with the number of ballots collected. But in many locations, outnumbered judges, facing crowds of rowdy would-be voters, some of whom were illiterate and couldn’t spell their names, let the record-keeping slip. In some precincts in bigger cities, officials emptied ballot boxes at hourly intervals and checked numbers of ballots against the number of names on the books, which allowed for some small degree of quality control.

After the polls closed, the officials retired to a back room wherever the voting had taken place (often a saloon or tavern) to count ballots and cross-check them with the poll books. These judges, who were supposed to be impartial, were in many places appointed by police, who in turn were appointed by city officials—so local partisan politics inevitably crept into the counting process. In Southern towns during Reconstruction or Northern cities under the sway of political machines such as Tammany Hall, officials could “lose” ballots or write down incorrect numbers, and there were few checks against these practices.

The accuracy of the count may also have been affected by the officials’ tendency to extend Election Day partying into the night. Charles Albert Murdock, who lived in San Francisco in the 1860s and served as a poll judge, recalled in his memoir: “One served as an election officer at the risk of sanity if not of life. In the ‘fighting Seventh’ ward I once counted ballots for thirty-six consecutive hours, and as I remember conditions I was the only officer who finished sober.”

Until the end of the 19th century, the corruption inherent in both voting and ballot-counting was generally accepted as part of the game. But during the election of 1876, when Republican Rutherford B. Hayes faced Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, disputes over ballot counts in three Southern states—Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina—delayed the results of the presidential race. Because Republican officials were in the majority on the panels that certified votes, they called for recounts and quickly declared that the states had actually gone for Hayes. Democrats contested the decision, going so far as to install alternate governors and state administrations rather than accept the legitimacy of the panels’ decisions. These recounts triggered a crisis on the federal level as Congress debated who held final authority to certify returns, and a president-elect wasn’t chosen for months. (Hayes won, but the vote-counting controversy was not without cost: The Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from Southern states, effectively ending Reconstruction.)

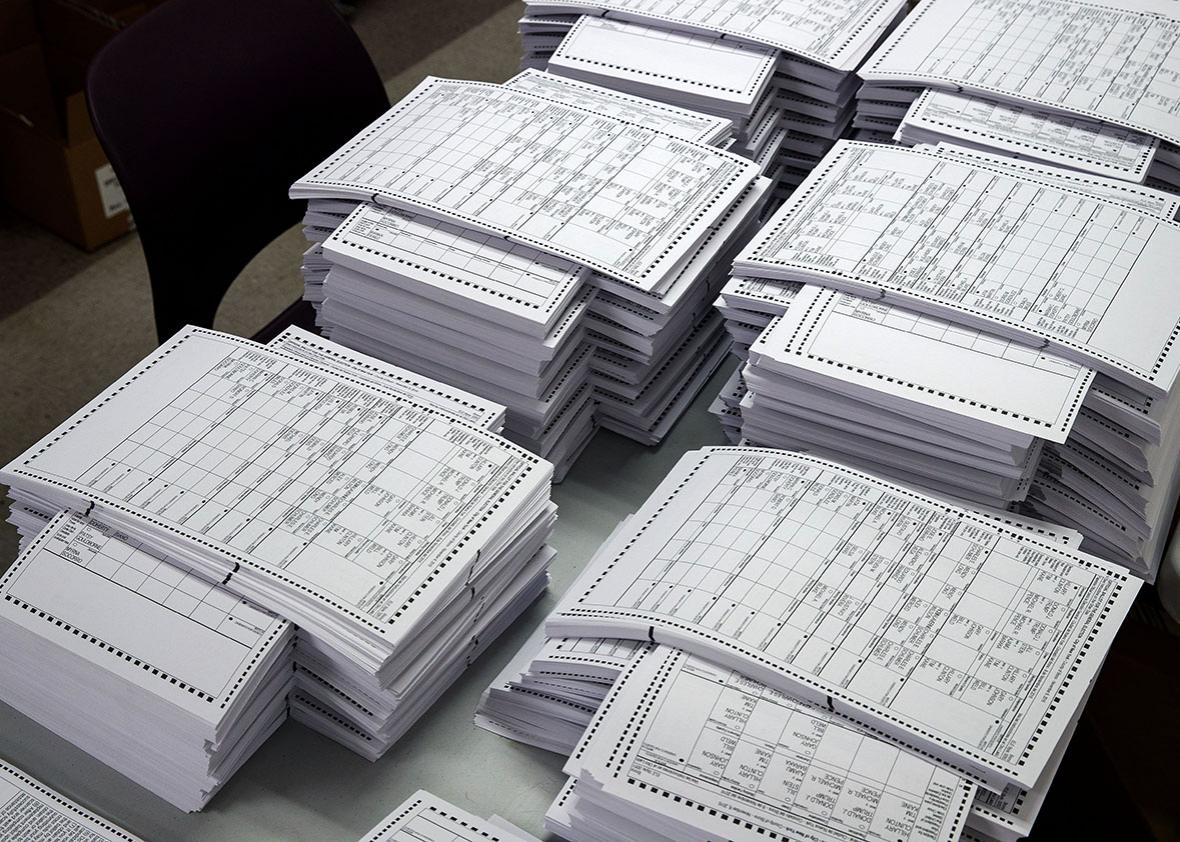

In response to the 1876 fiasco and to the influence of urban political machines, reformers called for the overhaul of the chaotic ballot system and succeeded in getting the so-called Australian ballot adopted in some forward-thinking states. In this system, the government printed a standardized ballot, which retains the secrecy of the voter’s choices while streamlining the counting process. There was still potential for corruption, however, since officials counting votes could willfully misinterpret voters’ checkmarks or stack tally teams with partisan allies willing to disqualify votes for the opposing candidate.

Mechanical lever voting machines, invented and adopted in the late 19th century, were supposed to circumvent the problems inherent in the hand-counted ballot, giving voters more secrecy while simplifying the counting process. The era of electronic vote-counting, which began in the middle of the 20th century, sped up election returns and regularized records, while bringing with it a new set of uncertainties—as anyone who followed the news in the fall of 2000 will recall.

Thanks to Jon Grinspan, curator of political history at the Smithsonian and author of The Virgin Vote: How Young Americans Made Democracy Social, Politics Personal, and Voting Popular in the Nineteenth Century, for his help.