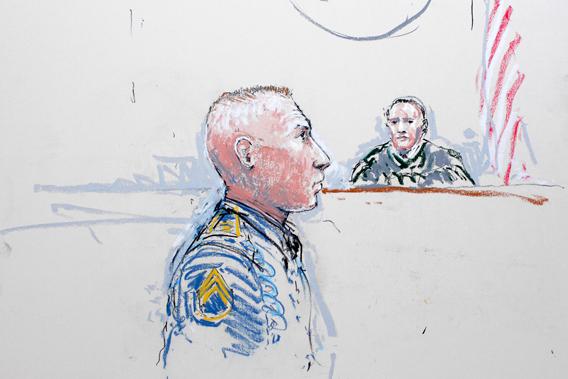

U.S. Staff Sgt. Robert Bales, who was charged with killing 16 innocent Afghan civilians in March 2012, pleaded guilty to premeditated murder in a military court on Wednesday. Why was Bales charged with murder rather than a war crime?

Because the U.S. military has jurisdiction over him. By deliberately killing unarmed civilians, Robert Bales broke a variety of laws. He violated Common Article Three of the Geneva Conventions, which protects “[p]ersons taking no active part in the hostilities,” as well as the War Crimes Act of 1996, a U.S. federal statute. He also violated the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which includes a provision for premeditated murder and applies to all U.S. service members serving anywhere in the world. Bales could have been prosecuted under any of those laws, but most military crimes are dealt with under the UCMJ, for a couple of reasons. First, soldiers serving abroad are under the command of military leaders, and the laws of war put the burden on those commanders to maintain discipline within the ranks. International law and international tribunals typically come into play only when those mechanisms fail. In addition, and perhaps more importantly, the UCMJ is a venerable legal regime. It has extensive safeguards for the defendant’s due process and a reliable appellate system. Although international criminal tribunals are growing in reputation, many observers favor the U.S. military justice system for its time-tested reliability.

International tribunals grab headlines, but the overwhelming majority of war crimes are dealt with under domestic laws like the UCMJ. After World War II, German courts and military commissions set up by the allies dealt with more than 20,000 war criminals, compared to a few dozen high-ranking officials tried at Nuremberg. Perhaps the most famous convicted U.S. war criminal, William Calley, was prosecuted under the UCMJ for his role in the 1968 My Lai massacre. The charge was premeditated murder, as was the case for Robert Bales.

Bales would likely have been tried for war crimes only if he had left the military prior to being charged. That’s what happened to Private First Class Steven Green, who raped and murdered a 14-year-old Iraqi girl in 2006. Green’s co-conspirators were all prosecuted under the UCMJ. Federal civilian prosecutors charged Green with violating the War Crimes Act, not because his behavior was more heinous than the others, but because he was discharged before his involvement in the crime became known, placing him beyond the reach of the military justice system.

Most legal scholars favor domestic trial and punishment because the penalties are tailored to the sense of justice of local people. In many countries, the death penalty is considered the only adequate punishment for murdering innocent civilians. When Bales was spared death, for example, an enraged family member of one of his victims vowed to take revenge. But at least execution was a possibility for Bales. The International Criminal Court is prohibited from considering the death penalty at all, so its punishment may leave some victims and their families feeling that justice was not served.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.

Explainer thanks Michael A. Newton of Vanderbilt Law School, author of Enemy of the State: The Trial and Execution of Saddam Hussein.