Much has been made about the many firsts Jorge Mario Bergoglio represents as the new pope: the first South American pope, the first Jesuit pope. He’s also the first pope with only one lung (that we know of). Pope Francis had one of his lungs removed as a teenager because of an infection. How much more difficult is life with only one lung? About one-quarter more difficult. One might suspect that losing one of two lungs would cut respiratory capacity in half, but it doesn’t, because the human body has significant reserves. The surviving lung soon expands to compensate for its missing mate, and regular exercise speeds the process. Otherwise-healthy post-pneumonectomy patients possess about 70 to 80 percent of their pre-surgical respiratory function. Although strenuous exercise becomes more difficult, especially at high altitude, and climbing stairs might trigger shortness of breath slightly more quickly, that deficit is hardly noticeable during ordinary activities. One-lunged runners have even completed marathons. There’s little reason to believe that Pope Francis is less physically capable of fulfilling the papal duties than two-lunged cardinals. Because he lost his lung to infection, his remaining lung is probably fine. He’s a rare case in the modern world, though. Antibiotics and public health programs have virtually eliminated pneumonia-triggered lung removal, and lung cancer now causes the overwhelming majority of pneumonectomies. Smoking has compromised the surviving lung in most of these patients. Today’s pneumonectomy survivors are typically in poor health for this reason, and they face significant risk from respiratory illnesses that would pose little danger to someone with two healthy lungs. Pneumonectomy patients sometimes have a visible lopsidedness. The nerve serving the diaphragm is often damaged in surgery, causing the patient’s chest to rise and fall unevenly. More importantly, when a lung is removed, something has to fill the space. The chests collapses slightly; the heart, liver, and remaining lung drift toward the void; and fluid fills the remainder of the cavity. Eventually, that fluid gelatinizes into a proteinaceous goo. As a result of all this movement, the spine can curve 15 to 30 degrees toward the lungless side, which is often noticeable to an observer standing behind the post-pneumonectomy patient. (The effect is much more visible on bare skin, so don’t expect to see the papal scoliosis anytime soon.) The drifting of organs into a lung-shaped void can occasionally cause health problems. The airway to the surviving lung can become impinged as it drapes over the spine, forcing surgeons to move everything back into place. They sometimes have to stuff foreign material, such as breast implants, into the chest to maintain proper anatomical geometry. Before the rise of breast enhancement, surgeons resorted to whatever was available, including sterilized pingpong balls. If you’re going to lose a lung, it’s slightly better to lose the left one. It’s only responsible for 45 percent of total capacity, because it shares chest space with the heart. It also has only two lobes, compared with three on the right. So left pneumonectomy patients have somewhat more remaining capacity than those who lose the right lung. In addition, organ drift after removal of the right lung is more likely to cause obstructed breathing, which can appear decades after the surgery. Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer Explainer thanks Stephen D. Cassivi of the Mayo Clinic, Scott Kopec of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, and Jonathan B. Orens of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Unus Pulmo

What’s life like for a one-lunged pope?

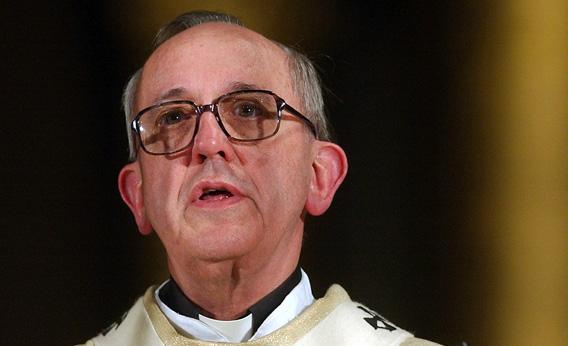

Photo by Natacha Pisarenko/AP

Advertisement