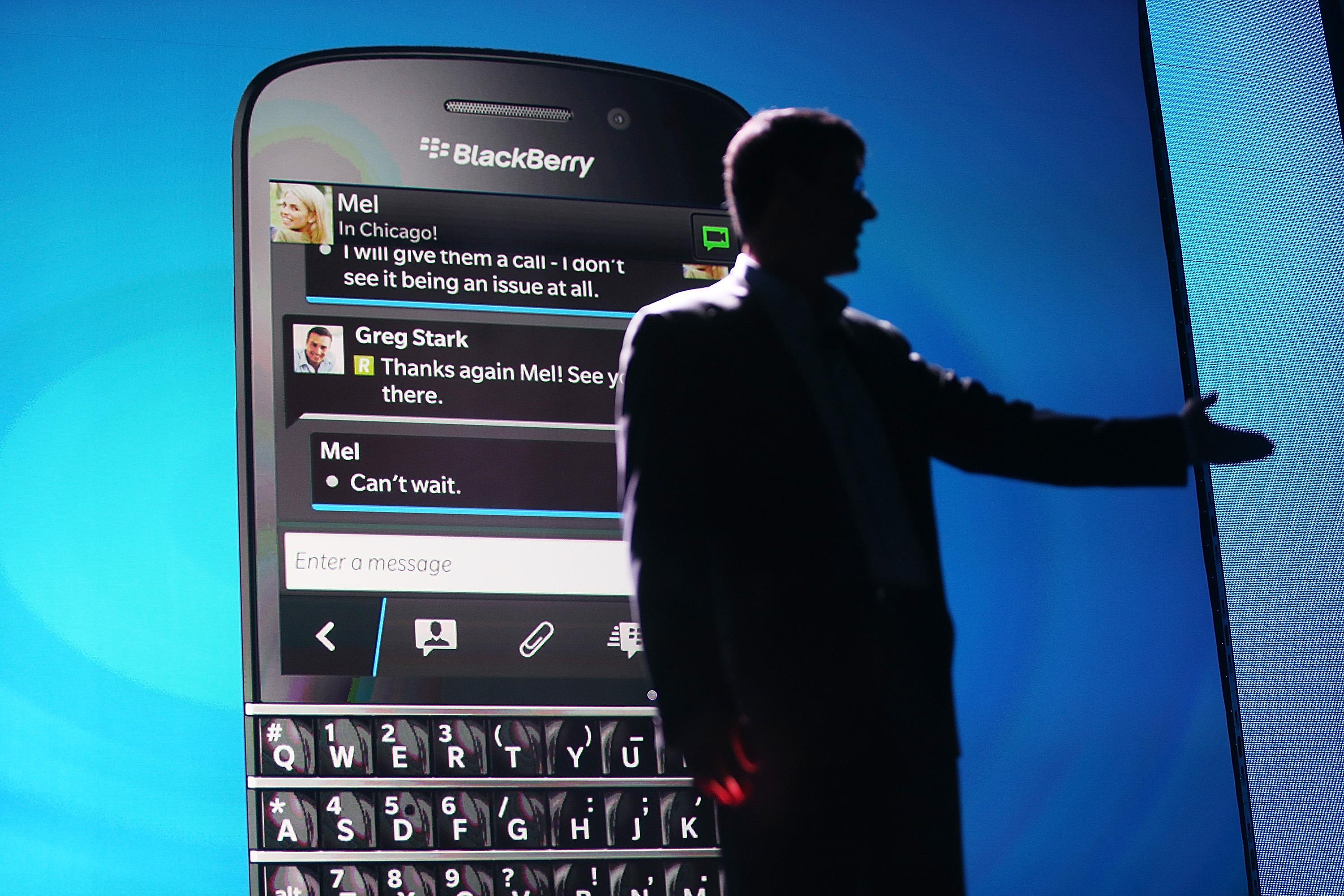

Research in Motion, the maker of the BlackBerry smartphone, changed its corporate name to BlackBerry on Wednesday. Do name changes save struggling companies?

Not usually. Most studies show that a name change has either little effect on a business’s long-term prospects or a mildly negative impact. A study of U.K. corporations, for example, showed that name-changers underperform compared with the overall stock market by almost 10 percent over the three years following the switch. That’s on average. Subdividing the data makes the future look even bleaker for BlackBerry, because the companies that tend to profit from name changes are fledgling businesses. When a new company changes names, it’s usually to broaden its product offerings or market reach. (A young company called Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo changed to Sony in 1958 so that Western consumers would have an easier time pronouncing the brand name.) When an established company changes names, it’s usually to break out of a slump—and it rarely works. Research in Motion/BlackBerry has seen its stock price drop 90 percent since its 2008 high. Corporations with falling stock prices prior to a name change perform even worse in the three years afterward, in part because the move smacks of desperation to investors. Shareholders don’t seem overly impressed with Research in Motion’s new moniker at this point. Although companies, on average, get a minor 4 percent bump in the days immediately following a name change, BlackBerry’s stock is down 12 percent after Wednesday’s announcement.

Changing names is quite expensive for a big company. Nissan originally sold cars in the United States under the name Datsun to protect the Nissan brand in case the new venture failed. Changing the name back to Nissan in the mid-1980s cost the company between $30 million and $100 million. In an interesting twist, Nissan is now spending millions to relaunch the Datsun brand. Navistar (formerly International Harvester), Unisys (the successor to Burroughs and Sperry), and UAL (United Airlines, briefly called Allegis) also spent tens of millions of dollars on advertising, headquarter redesigns, marketing consultants, and signage to reflect name changes.

These short-term expenses are nothing compared with the risk of naming a corporation after a single product or brand. If some calamity befalls its flagship, the corporation finds it difficult to escape the taint. When BP and Amoco merged in 1998, the company spent hundreds of millions of dollars erasing the Amoco name from 9,000 stations across the United States and remodeling them to reflect the BP brand. However, after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill soiled the Gulf of Mexico and BP’s reputation, investors urged the company to revert U.S. stations to the Amoco name.

There have been plenty of successful name changes. Some of the world’s largest corporations have rebranded themselves. In addition to Sony, Nike (Blue Ribbon Sports), Exxon (Standard Oil Company of New Jersey), and Olympus (Takachiho Seisakusho) all began with different names. But these success stories are simply highly salient exceptions rather than the rule.

The Explainer has one hot tip for investors: Companies can get a major bump by changing their names to take advantage of market hysteria. A pair of studies in 2001 and 2005 showed that companies that added “.com” to their names during the bubble of the late 1990s received a massive stock spike of 74 percent in the days after the announcement. Companies that dropped “.com” after the bubble burst earned a nearly equivalent 64 percent surge.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.