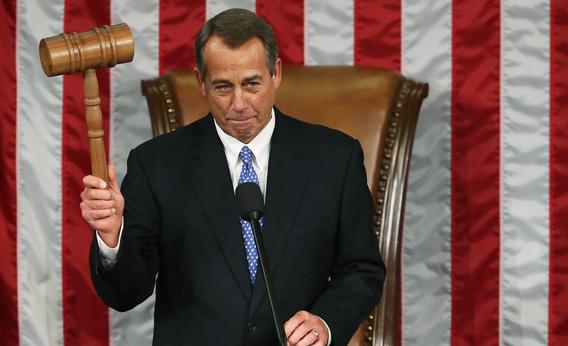

John Boehner was narrowly re-elected as speaker of the House of Representatives on Thursday. Dissident Republicans cast votes for former Secretary of State Colin Powell and Tea Party favorite Allen West, who was voted out of Congress in November. Do you have to be a member of Congress to be Speaker?

Probably. The Constitution states only that “The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers.” Many journalists, as well as the clerk of the House of Representatives, take this to mean that an outsider can be elected speaker. Even the Explainer once repeated this popular bit of constitutional mythology. Unfortunately, it probably isn’t true. The drafters of the Constitution likely took for granted that the speaker had to be a member of Congress. In his 1801 Manual of Parliamentary Practice, Thomas Jefferson likened the election of the leader of the Senate—and, by implication, the speaker of the House—to the British Parliament’s tradition of physically dragging the elected speaker of the House of Commons to the chair. That comparison is revealing, because the speaker of the House of Commons is elected from its membership. In addition, state legislatures always drew speakers from their own memberships, even though the state constitutions in place at the time the federal Constitution was drafted did not explicitly require it. Perhaps the clearest indication of the Framers’ intent comes from longstanding practice: Every speaker of the House has been a member of Congress. To the Explainer’s knowledge, no one from the founding generation ever cast a vote for a non-member. (The modern habit of voting for non-members is merely an act of protest, in any event.)

The Constitution lists explicit requirements for other offices. The president, for example, must be a natural born citizen, 35 or older, and a U.S. resident for at least 14 years. To serve in the House, you have to be at least 25 years old, a citizen for at least seven years, and live in the state you represent. The lack of explicit requirements for speaker implies to some interpreters that the framers deliberately opened the speaker’s post to anyone—an infant, a foreigner, or even a jar of jelly beans can hold the office. The other indications of the Framers’ intent, however, likely outweigh the Constitution’s vagueness on this point. Unfortunately, since the courts can’t decide the issue unless the House elects a non-member, this constitutional myth persists.

Although he has beaten Colin Powell’s unwitting challenge, John Boenher shouldn’t revel in his place in the line of succession. According to some legal scholars, he can’t ascend to the presidency. If the president and vice president are both incapacitated, the Constitution requires Congress to declare “what Officer shall then act as President.” The current federal succession statute, which provides that the speaker assumes the presidency under those circumstances, is arguably unconstitutional. In some contexts, “officer” refers to any government official, but the Constitution sometimes refers only to members of the executive branch as “officers.” There are some persuasive reasons to think the Framers would have considered the speaker ineligible for the presidency. For one thing, the speaker plays a role in impeachment proceedings, creating a conflict of interest. In addition, it’s impermissible to serve simultaneously in the legislative and executive branches. If the speaker had to temporarily assume the presidency—for example, if the president and vice president were simultaneously injured or missing—he or she would have to resign the legislative post. Once the president’s incapacity passed, the speaker would be out of a job.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.

Explainer thanks Vikram David Amar of the University of California-Davis; Michael Gerhardt of the University of North Carolina; Daniel Hulsebosch of New York University; Jeffrey A. Jenkins of the University of Virginia; and Ronald M. Peters, Jr. of the University of Oklahoma.