If elected, Mitt Romney “would arguably be the most actively religious President in American history,” according to a profile in the latest New Yorker. Who’s been our most religious president?

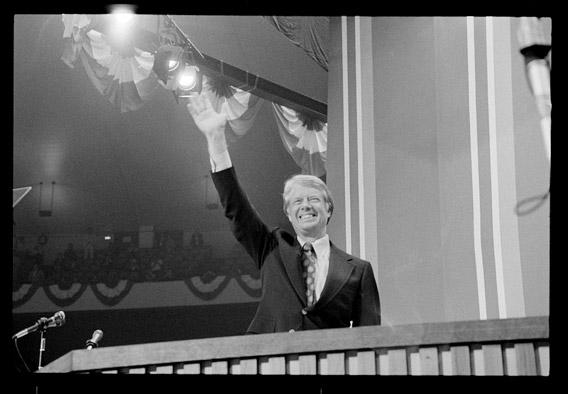

Jimmy Carter, probably. It’s impossible to know the contents of a man’s heart, but historians who study the religious lives of the presidents point again and again to the words and deeds of James Earl Carter Jr. The Georgia Baptist set a new standard during his 1976 presidential campaign when he described himself as “born again,” and he was frank about his religious beliefs throughout his presidency. While in office, Carter attended church wherever he went, even while on the road, and continued to teach Sunday school when at home. He prayed daily and read the Bible, and when he wasn’t reading the Bible he read theologians like Reinhold Niebuhr. Like Romney, he also knocked on doors as a missionary, addressing potential converts by saying, “I’m Jimmy Carter, a peanut farmer. Do you accept Jesus Christ as your personal savior?” Since his presidency he has continued his Christian mission on annual trips for Habitat for Humanity, and when he accepted the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize, he spoke of Jesus Christ as “the Prince of Peace.” His Secret Service codename was “The Deacon.”

Library of Congress.

Prior to Jimmy Carter, the most God-fearing U.S. president may have been James Garfield. Garfield is the only president who was actually a clergyman. At a young age Garfield became a minister for the Disciples of Christ, where he was lauded for his skill as a preacher, and he learned Greek—the original language of the New Testament. Though it was not his full-time job, he continued to preach and minister for years until his presidency. When he left his position to become president, he said, “I resign the highest office in the land to become President of the United States.” However, as Garfield only got to be president for six months before his death (he was assassinated by a religious zealot), there wasn’t much time for him to demonstrate divine pursuits while in office.

Other presidents who number among the most devout are the Methodist William McKinley, the Presbyterian Woodrow Wilson, and Unitarian John Quincy Adams. All of these men were fervent believers who attended church, prayed, and read the Bible regularly. Adams worshiped at three different churches (Unitarian, Presbyterian, and Episcopal) and would attend service even in heavy snow. He was also vice president of the American Bible Society and wrote religious poetry. During an 1846 debate over the Oregon territory (when he returned to Congress after his presidency), he cited the Book of Genesis. Abraham Lincoln is sometimes named among our most religious presidents, and indeed he had deep struggles with questions of religion. However, he did not widely profess his private believes and is known to have doubted the divinity of Jesus. Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama have been among the presidents to use the most religious rhetoric in their speeches, though this is partly due to the precedent set by Carter.

Bonus Explainer: Who was the least religious president? James Monroe or Ulysses S. Grant, perhaps—it’s difficult to say. There is little surviving evidence of Monroe’s religious beliefs, but what evidence there is suggests that from his 20s onward, Monroe wasn’t very religious and attended church infrequently. Grant seems to have refused to ever profess his faith, even when a bishop of his wife’s Methodist denomination pressed him on his deathbed. While Thomas Jefferson was called an atheist—he rejected the virgin birth, called the Book of Revelation the “ravings of a maniac,” and described the Trinity as a “hocus-pocus phantasm”—in his private life he was still a religious man who went to church and prayed.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.

Explainer thanks Darrin Grinder and Steve Shaw, authors of The Presidents & Their Faith; David L. Holmes, author of The Faiths of the Postwar Presidents; and Gary Scott Smith, author of Faith and the Presidency.*

Correction, Sept. 25, 2012: This article originally misidentified the author of the recent book The Faiths of the Postwar Presidents. The book’s author is David L. Holmes.