The Kennedys are back in the headlines today—this time it’s RFK Jr. That three-initial formulation, common to the Kennedy family since the 1960s, has lately appeared in headlines about French politician Dominique Strauss Kahn (DSK), Osama Bin Laden (OBL), and even LeBron James (often referred to as LBJ, though his middle name is Raymone). When did we start referring to famous people by three initials?

When we elected a president named FDR. His full name, of course, was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, but that was a mouthful. And referring to Roosevelts by their initials was a family tradition, probably because many in the clan shared first names. (There were multiple generations of James Roosevelts, for instance.) FDR’s mother, Sara Delano Roosevelt, sometimes went by SDR. And Franklin’s distant cousin, Theodore Roosevelt, may have been the first president to go by his initials in headlines, though in his case there were only two. “TR” seems to have caught on in his days as New York police commissioner in the 1890s mainly because the tabloids found “Roosevelt” unwieldy—to his friends, he remained “Theodore.” H.L. Mencken noted that some British prime ministers from around TR’s time also went by two initials in the press, including Campbell Bannerman (“CB”) and Lloyd George (“LG”).

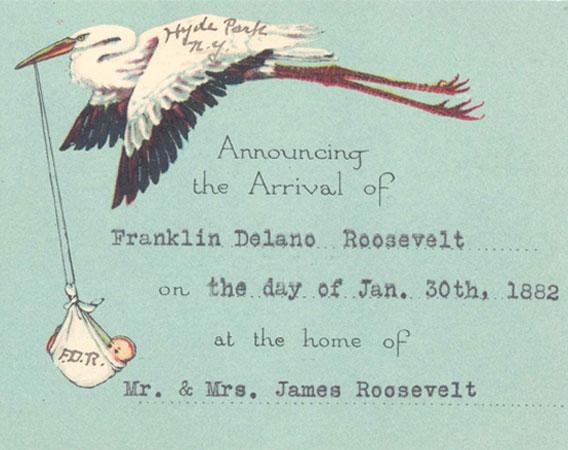

As for Franklin, the nickname was stamped on him from birth: A card announcing his arrival in the world on Jan. 30, 1882, depicted a stork carrying a bundle inscribed, “F.D.R.” Young Franklin apparently fancied the appellation, signing “FDR” on a letter he sent to a friend as early as age 9. Newspapers no doubt found the abbreviation especially handy, given that there had already been a President Roosevelt. (“FDR” appeared in the New York Times from the first year of his presidency.) Many of his New Deal programs were similarly stamped with three-letter initialisms (WPA, TVA, SSA, etc.). That may have been a coincidence, or it may have reflected a cultural trend, as companies such as IBM, RCA, NBC, and CBS had risen to prominence in the previous decade. (Three-letter abbreviations of business titles, such as CEO and CFO, came along much later.)

Given FDR’s popularity and longevity in office, it’s no surprise that subsequent Democratic presidents followed his example in nomenclature. Like FDR, John F. Kennedy wasn’t his family’s first prominent politician. His father, Joseph Kennedy, had served under FDR as chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

But perhaps the most enthusiastic—and calculating—adopter of the convention was JFK’s successor, Lyndon Baines Johnson. As a congressman, long before he became Kennedy’s vice president, he reportedly instructed an assistant always to refer to him by his initials: “FDR–LBJ, FDR–LBJ. Do you get it? What I want is for them to start thinking of me in terms of initials.” He didn’t stop there. His wife was conveniently nicknamed Lady Bird Johnson, and the couple gave their daughters (Lynda Bird and Luci Baines) names with the same initials. Even the family dog was Little Beagle Johnson.

By then the naming trend had spread to other public figures, including Martin Luther King Jr. (it’s possible “King” was too generic for abbreviation-seeking headline-writers), but it sputtered out among presidents with Richard Nixon. He titled his autobiography RN, but the press generally seemed content to use his full surname.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.

Explainer thanks H.W. Brands of the University of Texas at Austin, Bob Clark of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, Mark Liberman of the University of Pennsylvania, and Ben Zimmer of Visual Thesaurus.