At the end of this year’s historic session, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled on cases including the Arizona immigration law and mandatory life sentences for juveniles. In Thursday’s landmark health care case, growing speculation suggests that Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. will write the opinion. How does a Supreme Court justice write an opinion?

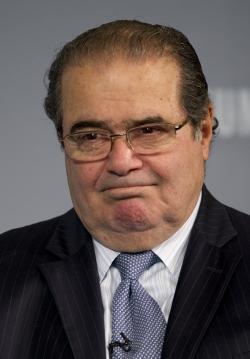

With lots and lots of help from their law clerks. While justices are responsible for the substance of their opinions in each case, their clerks usually do the majority of the writing. These clerks follow a code of secrecy about the process of writing each opinion, but we do know how the process generally works. After oral arguments and the initial vote, the senior justice for the majority opinion chooses a judge (who may be himself or another justice) to be responsible for writing the opinion. Unless this judge is Justice Antonin Scalia, who has often taken on the task of writing opinions himself, the judge will then usually select one of his or her clerks to take the first crack at drafting the opinion. The judge will then discuss with the clerk what the opinion should say and may provide a detailed outline or just a few rough notes. Each justice is allowed to have up to four clerks—bright young law graduates, usually from Ivy League schools and often in their mid-to-late-20s—with the exception of the chief justice, who gets to have five.*

Once the clerk is finished writing the first draft, which may involve painstaking research and working nights and weekends, the justice reads the draft and gives his or her revisions. These may be only a few small edits, or they may amount to a nearly complete rewrite, depending on the justice and the skills of the clerk. Sorcerers’ Apprentices, a 2006 book on the influence of Supreme Court clerks, found that about 30 percent of the opinions issued by the Supreme Court are almost entirely the work of law clerks, with clerks responsible for the majority of the court’s output. This is a relatively recent development: The Supreme Court began to institute clerks only in the 1890s, but by the mid-20th century they were already playing a significant role in drafting opinions.

After the responsible judge is happy with the opinion, it’s sent to the other chambers, traditionally carried by a court messenger. Any judges who voted with the opinion will tell the authoring judge if they have any suggestions or objections to the opinion, and there may be one or more rounds of revisions—implemented with the help of clerks and secretaries—to resolve these disputes. If they don’t like how the opinion turned out, and their objections are not resolvable, some judges will occasionally switch to the dissenting opinion (or write a concurring opinion), which is written at this time and circulates after the majority opinion. Otherwise they will signal that they are ready to join the opinion. Once each of the opinions is written, attorneys on the court’s staff proofread it one last time and check its citations. They also write the syllabus (which is a sort of executive summary or abstract) that goes above the opinion, and this is also sent back to the judges and their clerks for review. The finished opinion goes to press and often comes out very quickly after that, at which time it’s issued in the form of “slip opinions,” which resemble small pamphlets or booklets. These days the slip opinions are also published online.

The fact that these important documents are sometimes ghostwritten by young clerks has not been uncontroversial. Some scholars who study the court suggest that the clerks exert a small but significant influence on the judge’s decisions. In his book Closed Chambers, former clerk Edward Lazarus suggested that some judges function as little more than “editorial Justices.” This would explain why justices tend more and more to choose clerks who share their politics, and a 2008 study found that Democratic clerks make liberal decisions more likely, and vice versa. Clerks also seem to have contributed to a decline in the quality of the court’s writing. However, others have concluded that their influence is “rare and indistinct at best,” and in one survey former clerks tended to agree.

Bonus Explainer: In Monday’s decision on mandatory life sentences for juveniles, Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion apparently confused the name of a prison superintendent with that of a young murderer. How does the Supreme Court handle corrections? Unlike most major news organizations, the Supreme Court doesn’t publicize the changes it makes to its opinions. Instead, most errors that get through the court’s fact-checking are caught when the slip opinions are issued, and the necessary changes are made before the opinion is printed in the official record of the United States Reports (which are the big books you see at law libraries). The United States Reports aren’t published until months later.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.

Explainer thanks Mary-Rose Papandrea of Boston College, Artemus Ward of Northern Illinois University, and David Weiden of Hofstra University.

Correction, June 26, 2012: This article originally misidentified the Supreme Court justices’ clerks as law students. The clerks are graduates of law school, not law students. (Return to the corrected sentence.)