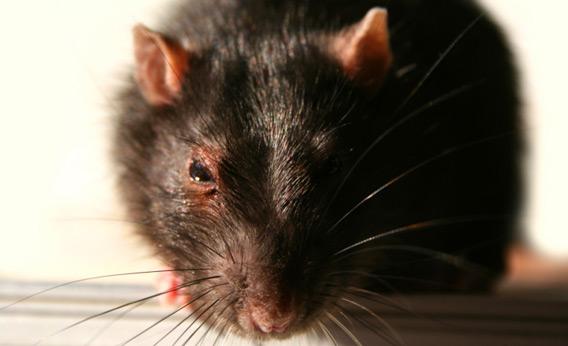

New York City police officers called attendees of the Brooklyn’s West Indian Day Parade “savages” and “animals” in a series of Facebook posts full of complaints about being assigned to the event. Some members of the online group warned others to watch their words, which could get them in trouble with “rats” from Internal Affairs, the New York Times reported on Monday. When did people start calling snitches “rats”?

In the first half of the 19th century. We’ve been denigrating each other for behaving like rats since the 16th century or before, but the usage of rat to mean informer is more recent. Perhaps the first appearance of the word as a reference to a tattletale comes from Thomas Moore’s 1819 satire The Fudge Family in Paris, in which the father Phil Fudge praises the “peaching Rat … false enough to shirk [his] friends” (to peach here means to snitch). By 1859 John Camden Hotten’s Slang Dictionary would define a rat as “a sneak, an informer, a turncoat,” and by the 1950s this meaning of rat was firmly entrenched in pop culture. In one LIFE magazine story from 1958, a gang member named Gus turns to a gang member named Rat and says, “Cause you a rat, is all. All you guys in the Fifth is rats. You ratted on us.”

It’s unclear exactly why people started to use rat in this way, but there are some possible explanations. Rat, as an epithet, has long referred to many different kinds of dishonorable people. Before calling someone a “rat” meant calling them an informant, it signified a drunkard, a cheating husband, or a pirate. It could also be used to label a deserter, in a reference to the animals’ legendary tendency to flee collapsing houses and sinking ships. This was especially true in politics: Jeremy Bentham, discussing what he saw as Silas’ defection from the Apostles of Jesus, wrote that “In the language of the modern party, Silas was a rat.”

Rat has since taken on even more meanings. Around the time that rat could first be employed in place of tattletale, it was also used by unions, especially in the U.S. printing industry, to describe those who refused to strike with the union. Americans started to “not give a rat’s ass” in the 1950s. In other cultures, rats conjure up similar associations. For example, in Spanish, a selfish miser can be called a rata, and to skip school is “hacerse la rata.” However, in some cultures, rats are thought to be more noble animals. In Hinduism, the god Ganesha is commonly accompanied by a rat, and the rats of the Karni Mata temple are considered sacred. Rats are also eaten in restaurants in many parts of Asia.

Of course rats aren’t the only double-crossers in the animal kingdom. Stool pigeon originally referred to a pigeon attached to a stool as a lure, but soon the phrase was used to describe people hired by casinos and other gamblers as decoys (such as to make the odds seem a little sweeter than they were). By the 1840s, the term was interchangeable with police informant, and by the 1920s, it had been shortened to stoolie. In the late 19th century, canary was used to refer to a female vocalist, but it soon became a common underworld term for those who would “sing” to the police. When it comes to moles, spy novelist John le Carré is often credited with inventing the term, but mole was used to refer to undercover agents as early as 1922. Still, le Carré does seem to have made it popular, both for the general public and among real-life spies as well. As stated in le Carré’s spy novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, “a mole is a deep-penetration agent so called because he burrows deep into the fabric of Western imperialism.”

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.

Explainer thanks Ben Zimmer of the Visual Thesaurus and Jesse Sheidlower of the Oxford English Dictionary.