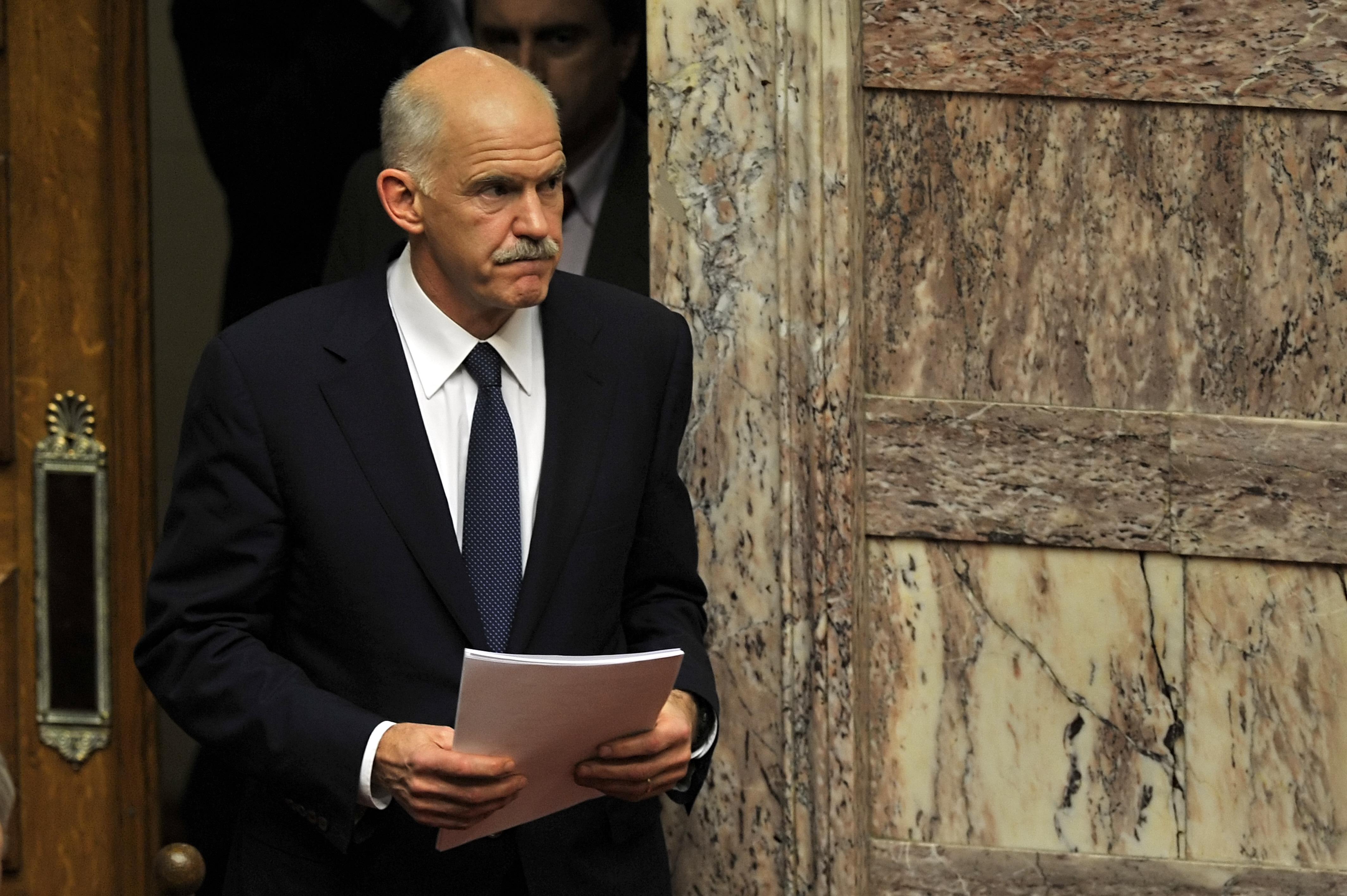

Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou is under fire for his decision to put a proposed $178-billion European bailout package to a referendum. Several prominent economists think Greece should simply drop the euro and return to its old currency, the drachma, in a move that would likely require a withdrawal from the European Union. How would a country go about quitting the E.U.?

First, the Prime Minister would send a letter of intent to the European Council. From there, the council bigwigs—the heads of each member state, plus a couple of E.U. executives—would have a lot of negotiating to do, since the details of how a withdrawal might work were left vague in the 2009 Treaty of Lisbon. They would consider, for example, whether the free trade and travel that exists within the European Union would still apply to citizens of a dropout state. The arrangement could be akin to the status of Switzerland, which doesn’t belong to the E.U. but enjoys many of the reciprocal benefits. The European Central Bank would also have to figure out how to refund the Greek contribution to its reserve capital—a total of 146 million euros. At the end of all this negotiating, a majority of council members would have to agree to the final settlement. (Greece wouldn’t get a vote.) If the negotiations failed, Greece could simply walk away from the E.U. two years after its initial notification, whether the other members liked it or not, and let the lawyers sort out the details.

It may be possible for the Greeks to withdraw from the euro but stay in the E.U., although the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (PDF) does not provide for this outcome. In fact, Article 140 of the treaty discusses members “irrevocably” replacing their old money with the euro. Some observers suggest that Greece might drop out of the E.U. temporarily, re-establish the drachma, and then rejoin the union (provided the rest of Europe would take them back).

If Greece did withdraw, it would seek to ease its debt burden by switching all of its obligations from euros to drachma. Then the Greeks could devalue their own currency, which would in turn limit their debts. This would create a new round of legal wrangling, however, as lenders fought to keep their payments denominated in stable and strong euros.

There’s very little precedent to resolve this potential dispute over currencies. Countries have changed over in the past, in accordance with the contract law principal of lex monetae. When Ecuador dropped the sucre in 2000, for example, it was able to change over its debts to U.S. dollars, their new currency. The Greece situation would be different, however, because, unlike the sucre, the euro would still exist. And the legal battle wouldn’t be limited to Greek sovereign debt. Every business in Greece that is a party to contracts with other eurozone members would also want to convert their obligations to drachma. Unless all of this were negotiated as part of a withdrawal from the E.U., the resulting situation would be incredibly messy.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.

Explainer thanks Michael Waibel of the University of Cambridge.