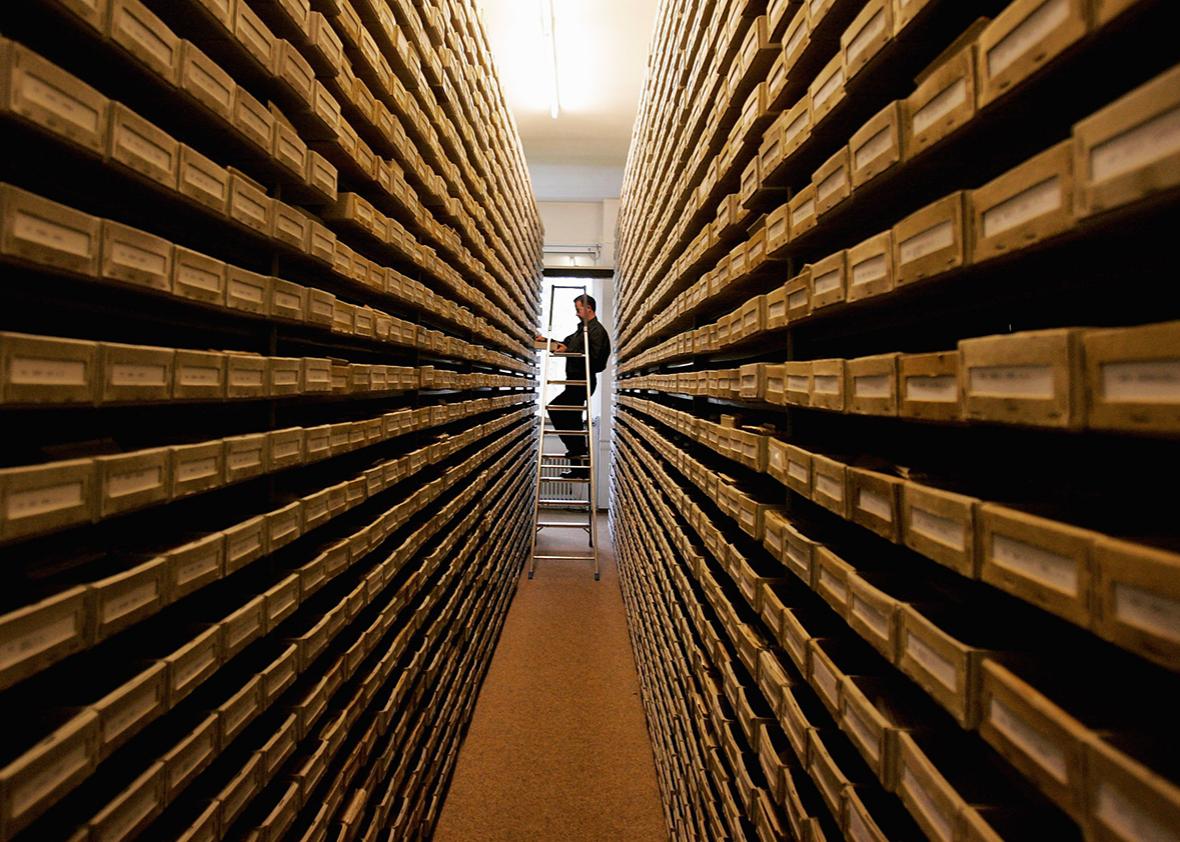

BAD AROLSEN, Germany—Udo Jost, a bearded, portly, unkempt man with strong smoker’s breath, gestures behind him toward a plate-glass window protecting a sea of library-card files. “What you see here is the main key to the International Tracing Service,” he says, speaking in German and pausing for translation, though he speaks English nearly fluently. “This is the Central Names Index—CNI—which covers three rooms and includes 50 million references for 17.5 million victims.”

Jost flips open an encyclopedia-heavy tome that explains an arcane alphabetic-phonetic formula developed in 1945 for researching Nazi victims’ names: In World War II prison camps, names changed from Cyrillic spellings to Germanic, Germanic to Francophone, Francophone to Polish, depending on who wrote down a prisoner’s details upon arrival in a work, concentration, or annihilation camp. In practical terms, that means there were 848 ways to spell the name Abramowitz, 156 versions of Schwartz. “ITS was not structured like an archive,” Jost continues. “The task was searching for victims and clarifying their fate. That’s why the documents could not be structured according to geographic or national criteria. Families searching for relatives generally did not know to which place their loved one had been deported.”

Jost has his patter down; he has begun to morph from chief archivist into tour guide. It’s a transition he never anticipated.

The International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen, Germany, was, until late 2007, the largest unopened Holocaust archive in the world. For decades, historians have begged to get inside these doors, the source of years of diplomatic tension between the United States—prodded by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum—and our European allies. Toward the end of the last century and the beginning of this one, it became the locus of hopes of survivors and researchers from all over the world, partly because no one really knew what they would find there. ITS holds some 50 million records. Sheltered in several buildings—once SS barracks—across a wide campus that recalls a New England liberal-arts college, the archives are located in a small farm village with a large palace, home to the fairy-tale-sounding character Prince Wittekind of Waldeck. (His godfather, staying with the period theme, was Heinrich Himmler.) By mandate, the archives were closed to research and outsiders beginning in 1955. That’s when the myths began.

“Nobody knew exactly what was inside,” Volkhard Knigge, director of the Buchenwald concentration camp memorial told me in the summer of 2006, after the international commission controlling the archives finally set a timetable to open ITS at a meeting in Luxembourg. “It became … a place of imaginations, of fantasies.” We spoke by phone, I in Madrid, Spain, and he in Weimar, Germany. “Nobody knows exactly whether we will find—[for example] documents about decision making on the part of perpetrators or administrations of the crimes of the Holocaust. This archive became a kind of black box, and it invited people to create ideas about why nobody had access.” Some thought the mystery was Germany’s fault, he told me; others believed that the administrators were keeping “files hidden to let survivors die so that they cannot prove their right for financial compensation.” Because it was a European rather than a German archive, some claimed that other nations had something to hide—perhaps proof of collaboration. Still others voiced concern that European privacy laws—stricter in many cases than those in the United States—would be violated if the files were opened.

What, exactly, was in the ITS collections was always a bit unclear. The basic facts were these: As the Allies crossed Europe, liberating concentration and labor camps, cities and towns, they collected documents left behind by the fleeing Nazis, and, over time, these collections were deposited—sometimes haphazardly, sometimes methodically—in Arolsen. Biographical cards from displaced persons camps ended up here, as did millions of files on forced labor, concentration camp inmates, Nuremberg, Nazi activity, and gruesome medical experiments—along with correspondence between Nazi officers, files on the dead, transport lists, sick lists, crime lists, and so on. The material covers political prisoners from across Europe, deported Jews, the millions of forced laborers from across Europe, and displaced persons—Jews who had survived the ghettos and camps as well as Eastern Europeans in flight from the Red Army. There are also post- and prewar photos and “personal effects”—rings, watches, photos—taken from prisoners. There are reams of postwar documents that follow the paths survivors took after the war

Efforts to trace the lost were run by a succession of international aid organizations including the U.N. Relief and Rehabilitation Administration and the International Refugee Organization. By the end of the war, the files at Arolsen were regularly used to answer queries regarding the millions of Europeans wandering the continent as well as about the millions of dead. Requests came in from every country touched by the war and, of course, from Jews. In 1948, the archives at Bad Arolsen became known as the International Tracing Service; seven years later, the management of the files was taken over by the International Committee of the Red Cross under what became known as the Bonn Accords.

The Bonn Accords mandated that the ICRC—considered an impartial institution—would control the files in Arolsen and that West Germany would be responsible for funding its operation. The holdings there were only to be used to trace survivors and victims—and to help families seeking restitution from the West German government. To alter that decree, 11 countries—Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, and the United States—would have to agree unanimously to open the doors. Israeli officials from Yad Vashem, the Israeli Holocaust memorial center, slipped in before the deadline to microfilm deportation lists from several concentration camps, but after that, the files were specifically designated to serve only those seeking family information or postwar victimization compensation. Under West Germany’s indemnity laws, victims had the right to pursue economic grievances against the German government for everything from being forced to wear the yellow star to death in a concentration camp. To obtain compensation, they had to somehow provide evidence of their experience—and a documentation file from ITS could do just that.

In the 1960s, ITS puttered along. But eventually the archive began to falter at its only task—tracing victims. Some say the biggest problems began with the arrival of Charles-Claude Biedermann, a Red Cross official appointed to take over ITS in 1985, who ruled the barracks at Arolsen like a fiefdom. He hired only local farm kids—who, for the most part, didn’t speak foreign languages—to staff the more than 300 stations inside the archives; they became (and remain) curiously specific experts in parceled areas of research—deportations to the extermination camps, say, or displaced persons. Biedermann encouraged those who worked in “general documents” not to speak to those who worked in “concentration camp archives,” the “displaced persons files,” or the “TD files”—tracing and documentation—and vice versa. Almost nothing was digitized.

In 1989, when the Iron Curtain fell, hundreds of thousands of new demands for information came pouring in, and a backlog of around 500,000 requests piled up. The wait for information began to stretch out over years; victims were dying before they found the information they sought on themselves—to receive long-overdue restitution payments—or their loved ones. Some survivors had never discovered the fate of siblings, parents, or spouses. Angry families and survivor organizations agitated for the archives to be opened to public scrutiny.

In 2001, representatives of the U. S. Holocaust Memorial Museum requested access to the files. They were denied. And then they began an intensive campaign to get inside—and to bring the files to Washington.

Three years later, after I wrote a story on three slave-labor camps in the heart of Paris for the Jerusalem Report, I was invited to an “on background” meeting with a handful of officials at USHMM. Could I write about the archives? they wondered. Perhaps it would put pressure on the 11 governments to change the Bonn Accords and open the archives to researchers and modernization in time for survivors to see their files. Magazines hesitated to commit to an in-depth piece on an archive that I wasn’t allowed to see.

And yet like many without access to Bad Arolsen, I couldn’t forget the archives.

Half the academics I spoke to were reverential about what they believed was hidden at Bad Arolsen; the other half thought the myths were just that—trumped-up stories and rumors. Those obsessed with the archives were just as fascinating as the archives themselves: What exactly were people hoping to find?

After the commission’s 2006 meeting in Luxembourg, it took two more years for the archives to open their doors. In the meantime, I began to petition the USHMM to allow me to accompany them to Bad Arolsen along with the first group of scholars selected to start research there—a trip eventually slated for the summer of 2008.

I had another, more personal, reason to travel to Bad Arolsen.

After we packed up my grandparents’ house in northwest Massachusetts upon my grandmother’s death, I came across a box of letters marked “Patients’ Correspondence.” My grandfather had been a family physician in the United States after he fled Nazi-occupied Vienna. But inside the box I discovered not only letters from his patients in New York and Massachusetts but dozens upon dozens of letters from family and friends in Vienna, Berlin, Lyon, and Shanghai—all begging my grandfather, who had safely made it out, to cast the lifeline back and bring them over as well. About 50 of the collection were love letters. They were not from my grandmother. Written by a woman named Valerie Scheftel, the letters were baldly needy: She was desperately in love with my grandfather, and she was trapped in Berlin.