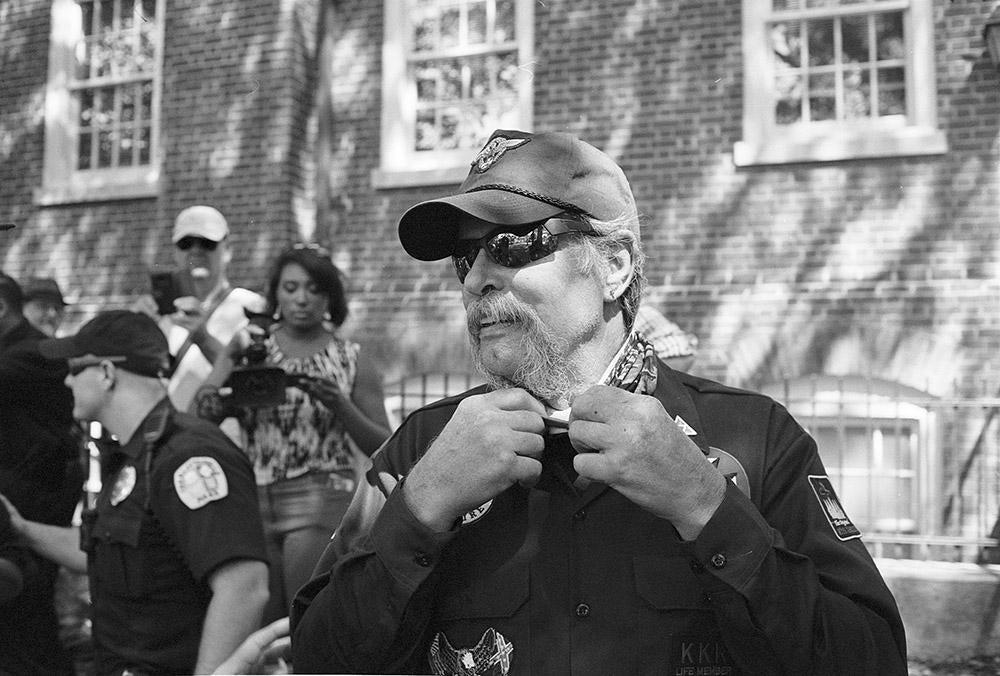

On July 8, 2017, the Ku Klux Klan came to Charlottesville, Virginia, to protest the removal of two statues commemorating Confederate generals: one of Robert E. Lee, the other of Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

Jamelle Bouie

The rally wasn’t a surprise. This chapter of the Klan, the Loyal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, had obtained permits for their protest in the spring. Soon after, locals began organizing events to coincide—from concerts meant to keep people from the circus to a direct counterprotest. As the day of the Klan rally approached, city leaders encouraged residents to stay away. That plea fell on deaf ears.

Jamelle Bouie

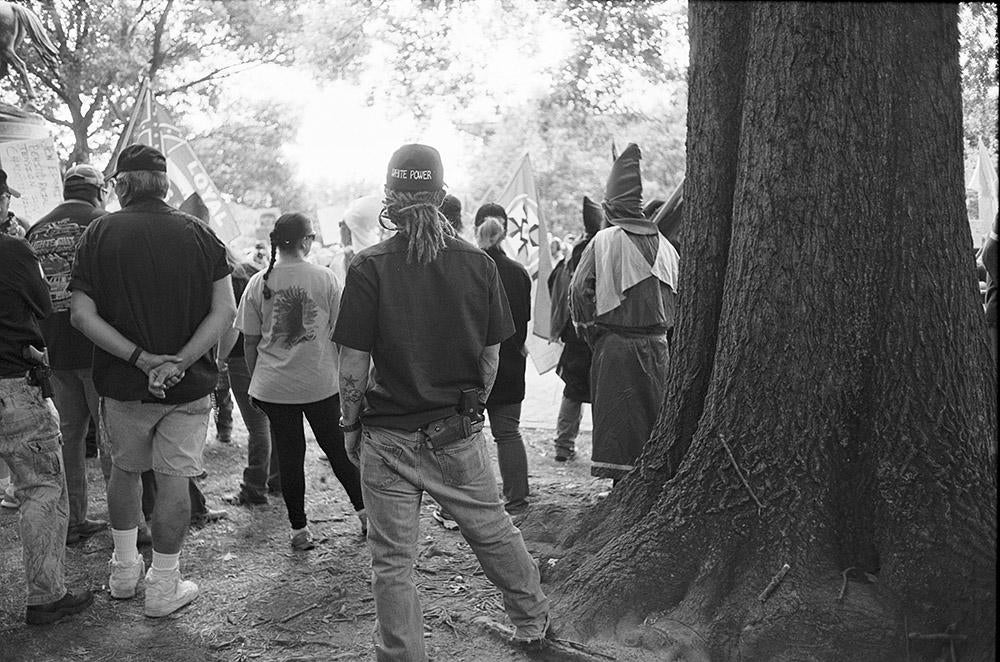

Around 50 Klansmen came to Charlottesville, but more than 1,000 people gathered in response, yelling anti-Klan slogans and otherwise taunting or mocking the assembled white supremacists. Those protesters ranged from clergy to college students, from Black Lives Matter activists to the local chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America. Some Klansmen were armed, and local and state police were there to keep the peace. But if anyone was in danger, it was the Klan members, not the protesters.

Jamelle Bouie

The Loyal White Knights had come to Charlottesville to stand up for “white rights.” But what they actually did was demonstrate their irrelevance and show the extent to which this incarnation of the KKK is a far cry from its larger, more dangerous predecessors.

But while the Klan is a faded image of itself, white supremacy is still a potent ideology. In August, another group of white supremacists—led by white nationalist Richard Spencer and his local allies—will descend on Charlottesville to hold another protest. Unlike the Loyal White Knights, they won’t have hoods and costumes; they’ll wear suits and khakis. They’ll smile for the cameras and explain their positions in media-friendly language. They will look normal—they might even be confident. After all, in the last year, their movement has been on the upswing, fueled by a larger politics of white grievance that swept a demagogue into office.

The Klan, as represented by the men and women who came to Charlottesville, is easy to oppose. They are the archetype of racism, the specter that almost every American can condemn. The real challenge is the less visible bigotry, the genteel racism that cloaks itself in respectability and speaks in code, offering itself as just another “perspective.” Charlottesville will likely mobilize against Spencer and his group, but the racism he represents will remain, a part of this community and most others across the United States. How does one respond to that? What does one do about that?

Jamelle Bouie

Jamelle Bouie

Jamelle Bouie

Jamelle Bouie

Jamelle Bouie

Jamelle Bouie

Jamelle Bouie

Jamelle Bouie

Jamelle Bouie

*Update, Sept. 13, 2017: This caption has been update to remove the name given by the subject because his identity could not be independently verified.