BOSTON—Survivors of the Boston Marathon bombing gathered in the Moakley Courthouse on Wednesday morning, transforming the hallways into a forest of prostheses. Their friends and families were here to offer emotional, and sometimes physical, support. The attorneys had come, and the judge, and the media scrum. And of course the defendant, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, had been dragged here in chains.

Yet it wasn’t clear, in a certain sense, precisely what we’d come here for. Yes, this was the day of Tsarnaev’s sentencing, and a separate day of sentencing for a guilty defendant can serve an important purpose. Victims can make statements they hope will sway the judge to throw the book at their aggressor. The defendant might try to persuade the court, through a show of remorse, to exercise mercy and reduce his time in jail.

But there was almost nothing left to be decided here. In a federal death penalty trial, it’s the jurors, not the judge, who determine the defendant’s fate. And the jurors in this case had already condemned Tsarnaev to die. At the court today Judge George O’Toole had some technical business to attend to—for instance, he issued sentences for the non-capital crimes Tsarnaev had been convicted of. But given that Tsarnaev faces the death penalty, the exercise with regard to these lesser offenses was moot.

So what were we looking to achieve on this day? Was it mere formality? Or were we after something more? What sort of closure did we hope to find?

In part, this was a day to ensure that victims’ voices were heard. Many survivors who had not testified during the trial now came before the court. They spoke of lost limbs, broken bones, impaired hearing. Months of surgeries, ongoing pain, derailed careers, strained marriages. Flinching at sudden noises. Waking from nightmares, screaming. Each had lived, and was still living, a tragedy, and it was proper to let them unspool their burdens to us before this proceeding came to an end.

Some spoke bitterly about the things they would never regain. Some instead chose to emphasize the beauty they’d discovered ever since this ugliness had engulfed them—the selfless help they’d received, the communities that had grown out of the trauma. One man expressed his wish that the people of the world could come together in this aftermath and find a way to coexist.

Jennifer Rogers, sister of slain MIT police officer Sean Collier, used part of her statement to air her frustration with the press. She described her “first media assault,” which came shortly after she’d gone to the hospital where Collier was brought after he was shot. “She was young looking and blended in quite well,” Rogers said of the reporter she encountered. “And I saw how our grief would be treated: as a salacious story. Soon after, the press was on the porch of a neighbor’s house trying to get pictures of us crying. I’ve had to call the police because this was a regular occurrence. … The media know my phone number and email, and they stalk us on Facebook.”

But many of the victims—and especially the ones who’d lost the most—turned their sights on Tsarnaev. Patricia Campbell, whose daughter Krystle died on Boylston Street, trembled and cried as she looked at Tsarnaev and said, “I feel your parents brought you here for a reason, for a better life. And intellectually you’re pretty bright. You could have helped your brother get help. I know life is hard but the choices you made are despicable.” She then broke down, losing control. “I don’t know what happened! … I don’t know what to say to you!”

Krystle’s friend Karen McWatters, who lost her leg in the bombing, said Tsarnaev “can’t possibly have had a soul to do such a horrible thing.” She shook her head at the legal effort to portray Tsarnaev’s brother Tamerlan as the real perpetrator. “What a cowardly defense,” she complained.

Again and again, the victims wondered if Tsarnaev felt remorse. And if he did, they asked, why hadn’t he shown it? Over and over, they mentioned his demeanor during the trial.

Jennifer Rogers described the way he walked into the courtroom surrounded by marshals each morning, “his head held high with a swagger in his step like he was entering a party with his entourage.”

“Everyone has watched you basically gawk at the horrific footage with little to no remorse,” said amputee Rebekah Gregory, addressing Tsarnaev directly. She noted she’d seen him “fiddling with your pencil and cracking jokes with your attorney.”

“The first time I saw you in this courtroom you were smirking at all the victims,” said Ed Fucarile, whose son Marc lost his right leg. “You don’t seem to be smirking today.”

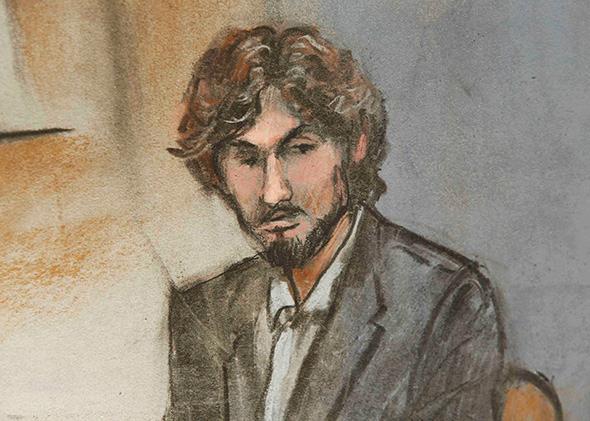

When I wrote about Tsarnaev’s slouchy, fidgety bearing earlier in the trial, Susan Bandes, a professor at the DePaul University College of Law, emailed me a study she’d done on defendants’ body language. “There’s no clear way to communicate remorse,” she argued in her email. She may have a point. But certainly, if Tsarnaev wanted to convey how seriously he was taking these proceedings over the last few months, he could have sat up straighter. He could have shaved, and trimmed his indulgent mop of hair. He could have put on a tie. Even today, as victims spoke directly at him, some of them mentioning their frustration that he didn’t look at witnesses as they spoke, Tsarnaev continued to stare at the wall or at his knees.

And remorse seemed to be the only thing the victims wanted from him. They expressed a deep, profound need for him to see the error of his ways. Bill Richard, father of 8-year-old Martin, who was killed by the bomb Tsarnaev carefully placed a few feet behind him, noted that he and his wife had opposed the death penalty for Tsarnaev. “We’d preferred he have a lifetime to reconcile with himself what he did that day,” said Richard, “but he will have less than that. Until the day he asks for reconciliation this all hangs on him. And on the day he meets his maker may he understand what he has done and may justice and peace be found.”

Other victims, one after another, pleaded with Tsarnaev to think about what he’d done, to apologize. But he remained a cypher. It seemed we’d never know whether Tsarnaev felt any contrition whatsoever.

And then, to the amazement of many who’d been following the trial, defense attorney Judy Clarke announced that her client would speak. Tsarnaev rose to his feet. He talked softly, and calmly, almost politely. He praised Allah and Muhammad, and he noted that this is the month of Ramadan—a month of “mercy” and “reconciliation” and a month “during which hearts change.”

“You told me how horrendous it was, this thing I put you through,” he said of the witnesses who’d taken the stand. “I wish that four more people had a chance to get up there but I took them from you.” And then it came. An apology. “I am sorry for the lives I’ve taken, for the suffering I’ve caused you, and for the damage that I’ve done.”

It was, at last, the remorse everyone had begged him to express. But somehow it didn’t sound like remorse. It sounded more like a stone-faced military general, speaking from the podium after a battle victory, allowing that he felt some mild regret regarding the collateral damage that was necessitated by the greater mission of the war.

His speech was anticlimactic. I don’t know what we were expecting, all of us brought together today to train our full focus on a young man who has displayed no shred of humanity. Tsarnaev never said that he wished he hadn’t detonated that bomb. Nor had he taken the stand during the trial to explain his actions—that would have meant facing a withering cross-examination. Instead, he spoke in this controlled, protected setting, where no one could interrupt him or ask him questions or in any way invade his walled-off mind.