It took the jury about 14½ hours to decide it wanted to kill Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. I take longer than that to pick out a pair of pants when I’m shopping online.

Still, it’s more time than it took a jury to sentence Timothy McVeigh to death—and he committed perhaps the most analogous federal crime in recent memory. The two cases both offered clean scenarios: no doubt about who did it, no doubt that the offense was horrific. If you believe in capital punishment as a valid form of justice, these would seem like pretty good moments to impose it.

I did find some of the jury’s reasoning, as recorded on the verdict form, baffling. Only three out of 12 jurors agreed with the defense team’s contention that Tsarnaev would not have committed any of his crimes if not for the influence of his older brother, Tamerlan Tsarnaev. That’s nuts. Tamerlan was clearly in the driver’s seat, in my view. Without Tamerlan, I think Dzhokhar is three bong hits deep and playing Xbox this afternoon. Likewise, only five jurors agreed that Tamerlan had become radicalized first and then encouraged his younger brother. Again, I’m not sure what trial the rest were watching—to me, the evidence was clear that, however radical Dzhokhar eventually became, Tamerlan was the one who arrived there first.

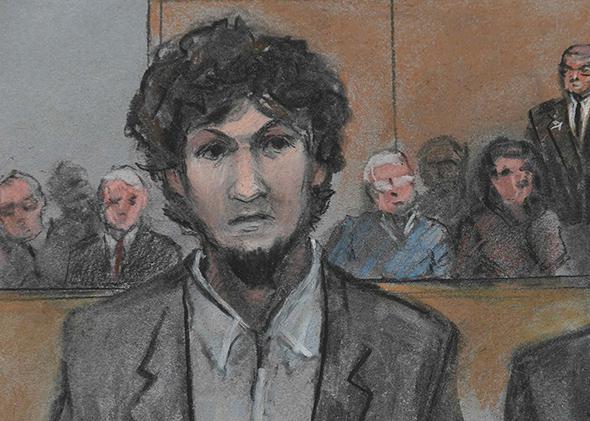

On the all-important question of remorse, the jury was clear: They agreed with the government’s contention that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev had shown none. Was it his defiant manifesto inside that dry-docked boat? Was it the middle finger he was caught flipping by the security camera in a courthouse holding cell? Was it his slouching and fidgeting, his inscrutable expression, as he listened to victims describe the devastation that he’d wrought? Unless and until jurors speak to the media, we won’t know.

Defense attorney Judy Clarke’s stellar record has taken a ding here. She spared Ted Kaczynski, Susan Smith, and Jared Loughner from execution, but couldn’t do the same for Tsarnaev. At least, not yet. No doubt, we’ll get years of appeals in this case before Tsarnaev is killed. If he’s ever killed at all.

The most obvious grounds for reversal: the grounds of the courthouse. Or rather where they’re located, walking distance from the finish line of the marathon. The defense team fought hard to move this trial to another city. Judge George O’Toole—stubbornly, in my view—refused to let the case leave, arguing he could seat an unbiased jury. This even though the crime had been waged in many ways against the city itself, had riveted everyone in Massachusetts for the better part of a week, and had shut all of Boston down for an entire day as citizens were ordered to shelter in place during the manhunt.

Today, thanking the jurors for their service, O’Toole told them they’d acted “on behalf of a community seriously aggrieved.” Whoa, hold on a second. I thought they’d rendered a verdict on behalf of the victims and their families or, more technically, on behalf of the United States government. The very notion that they were acting on behalf of all of eastern Massachusetts would have been, reassuringly, taken out of play if the trial had been shifted to, say, Washington, D.C. There it would have been heard by a jury feeling no pressure to quench a regional thirst for vengeance.

I don’t quite know where to place Tsarnaev in the taxonomy of monsters. This wasn’t a moment of clinical insanity, like James Holmes in that Aurora, Colorado, movie theater. This wasn’t 17 years of targeted assassination attempts, like the Unabomber. This was a tragically misguided political statement from a 19-year-old idiot. Several months of planning and a week of mayhem from a dorm-room jihadi.

“’t’s morbid, watching a poor devil on trial for his life,” says Miss Maudie in To Kill a Mockingbird, explaining why she declines to go to the courthouse to watch Atticus Finch argue on behalf of Tom Robinson. “Look at all those folks, it’s like a Roman carnival.” And it was, a bit. The similarities between that fictional case and the real one that concluded on Friday end there. But the description still feels apt. Photos of carnage and testimony from weeping victims as we all looked on, gawking: groups of students lining up to observe the proceedings as a form of civic education, throngs of media cracking gallows jokes in the overflow viewing areas. I would say the only indisputably good thing to come out of today is the fact that it’s all over. But it’s not. We’ll reconvene some day, with Tsarnaev’s life still hanging in the balance.