BOSTON—We assembled in Boston’s Moakley Courthouse this morning for a proceeding so stark it felt more like ancient Greek drama than like a Tuesday in 2015. It’s not often that I’m party to a ritual in which a man’s life hangs in the balance.

“It is impossible for me to overstate the importance of the decision before you,” said Judge George O’Toole to the jury as the sentencing phase of United States v. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev began. Once both sides have had their say, these jurors—having already pronounced Tsarnaev guilty on all counts—will face the most binary of choices: Kill the man? Or let him live?

There was little unexpected in prosecutor Nadine Pellegrini’s opening statement. She displayed pictures of the four dead victims, repeatedly calling them “beautiful” and noting that none would ever see their 30th birthdays. She described the grief their families had felt every day since they’d been murdered. She ticked off a list of aggravating factors that might convince the jurors that Tsarnaev deserves to die—among them, the planned and premeditated nature of the bombing, the “heinous, cruel, and depraved” method used to kill, the excruciating physical pain the victims would have endured in their final moments, and the vulnerability and innocence embodied by 8-year-old Martin Richard.

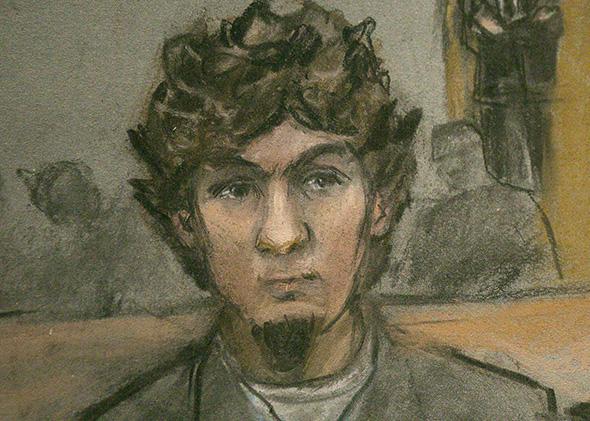

Pellegrini did have one surprise up her sleeve. As she drew to her conclusion, she informed the jury that on July 10, 2013, about three months after the bombing, Tsarnaev had been left alone in a room with a camera (it appeared to be a holding cell) here inside the courthouse. “He had one last message to send,” she said tartly, as she unveiled a big poster. It was an enlarged photo of Tsarnaev—wearing orange prison scrubs and scowling furiously—as he flipped his middle finger directly at a ceiling camera in the cell.

We don’t know if he’d just been denied lunch, or if a guard had just elbowed him in the stomach and thrown him against a wall. But without any context, this was an ugly portrait of the defendant. It sat before the jury as Pellegrini gave her final assessment of him. Tsarnaev, she asserted, was “unconcerned, unrepentant, and unchanged.” He was “without remorse.”

Defense attorney Judy Clarke declined to make her opening statement Tuesday. She’ll wait until the prosecution’s rested, then start fresh, creating her own portrait of her client. She will no doubt attempt to paint Tsarnaev as a patsy of his older brother, Tamerlan. As a regular teen who fell under the influence of a domineering family member. She’d begun to present evidence to this effect during the guilt phase of the trial. But one thing she did not—or could not—present was evidence that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev has felt any of the remorse that the prosecution says he is devoid of.

This is crucial, I feel, to Tsarnaev’s fate. I could see the jurors forgiving him for becoming Tamerlan’s dupe. But not if they think he still can’t admit the error of his ways and would do it all over again. If the jurors believe Dzhokhar Tsarnaev has shown no remorse, they will be hard-pressed to show him any mercy.

Where does the truth lie? Has Tsarnaev changed his mind about what he did? We just don’t know. We can’t know unless he testifies as much, or someone else does on his behalf. We can see, however, his body language in the courtroom. And though it’s risky to read too deeply into slouches and tics, Tsarnaev certainly hasn’t made much effort to appear chastened or regretful before the jury. The closed-circuit cameras that were broadcasting from the courtroom to the media room Tuesday were not high-resolution enough that I can 100 percent swear by this, but: I’m pretty sure that after Pellegrini showed that photo of him flipping the bird, Tsarnaev smirked.

Before this trial began, during jury selection, I’d have bet good money that Tsarnaev would escape capital punishment. Judy Clarke is known as one of the best lawyers in the world when it comes to securing evildoers life without parole instead of state-imposed death. And she needs just a single juror to find, within him or herself, a shred of sympathy for Tsarnaev. In order to execute, the jury is required to be unanimous.

Now, though? After this same jury convicted Tsarnaev on all 99 questions at issue in the guilt phase—even though some of them were far from no-brainers? After seeing that scowling photo and watching Tsarnaev’s jaunty posture these past several weeks? I’m not so sure.

Nor am I sure what I would do in the jury’s shoes. Of course, we’ll wait to see what sort of defense gets presented on his behalf. It’s still possible, if improbable, that he’ll speak for himself. But if I imagine that the trial were ending right now and I were asked to make a ruling on his life … I’d be torn. I am opposed to capital punishment on the grounds that I simply don’t trust the state to apply it fairly, competently, and without racial bias. But in this specific case, where the killer has admitted his guilt and the crime is so abhorrent? It’s less clear-cut to me.

Whenever people learn I’m covering Tsarnaev’s trial—whether it’s around the table at a Passover Seder or out at a bar after pickup basketball—the question always comes up. Some feel the harsher punishment is to chuck him in a box for the next 70 years. (Not for nothing: a box the New York Times calls “a cleaner version of hell,” and one that seems specially designed to drive its inhabitants insane.) Others, including people I might not have expected, have been more implacably vengeful in an Old Testament sort of way. “I don’t want him eating food,” said one friend. “I don’t want him breathing air. I don’t want him moving around in his body.”

We do know what Martin Richard’s parents think. Bill and Denise Richard, who watched a son die and a daughter lose a leg, wrote an open letter to the Justice Department suggesting a plea in which Tsarnaev would be spared but would spend life in prison and would waive all appeals. Basically, they want him to disappear as soon as possible.

It’s easy to believe that at least a few of the jurors have been made aware of this letter. It ran on the front page of the Boston Globe on Friday while court was not in session. Will it affect the way they treat Tsarnaev?

This letter is one of the many reasons that this trial should never have been held in Boston. Another? The Boston Marathon—full of tributes to the heroes and remembrances of the victims from 2013—was run just yesterday. The finish line was a not-very-long walk from the courthouse door. People walking the streets still had on their official warmup jackets, and the marathon signage was everywhere you looked.

The judge asked jurors not to watch the race, or read about it, or talk about it. Did they obey this order? And did they shield their eyes from the Richards’ letter? Have they been fully insulated from the rapt, furious attention of the city around them? I wouldn’t bet my life on it.