At this morning’s opening statements in the trial of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the alleged Boston Marathon bomber, two things became clear: 1) The prosecution has amassed mountains of evidence implicating Tsaranev—the heft of it certain to be convincing, the grains of it certain to be horrifying. 2) The defense team doesn’t care. For them, this trial will begin only after Dzhokhar is found guilty.

A few minutes before 9 a.m., prosecutor William Weinreb stood alone near the center of the courtroom, staring at the empty jury box. He fiddled with his lectern and microphone. He appeared to be steeling himself to deliver his opening monologue. Soon the jury filed in, the judge offered opening remarks, and then Weinreb began to describe in detail the death, anguish, and destruction wrought by the bombs that exploded near the marathon finish line in April of 2013.

He spoke of surveillance tapes that show Dzhokhar at the scene of the crime, lingering just behind a group of children—among them Martin Richard, an 8-year old boy who was ripped apart by the explosion from Tsarnaev’s backpack bomb. Weinreb talked of other footage, as well: video of Dzhokhar, 20 minutes after the bombs went off, calmly shopping at a Whole Foods grocery store, where he purchased a gallon of milk and then switched his mind and exchanged it for a different gallon of milk. Weinreb quoted from Dzhokhar’s Twitter account in the wake of the bombing (“I’m a stress-free kind of guy”), from text messages he sent to a friend (“I saw the news. Better not text me. LOL”), and from the screed Dzhokhar penciled on the hull of the dry-docked boat that he hid in during the police manhunt (“I ask Allah to make me a shahied to allow me to return to him and be among all the righteous people in the highest levels of heaven”).

Weinreb concluded by showing the jurors photos of the four dead victims. First came pleasant-faced Sean Collier, the MIT police officer whom Dzhokhar and his brother Tamerlan allegedly shot point-blank in the head three times. Then a photo of 29-year-old Krystle Campbell, here looking happy and lounging in a Tom Brady football jersey—as the jury looked at her face, Weinreb told them that “her back was burned red.” Lingzi Lu, the 23-year-old Boston University graduate student, was pictured sipping from a coffee mug as Weinreb mentioned the “perforating holes in her legs.” And finally Martin Richard, the tiny 8-year-old from Dorchester, wearing a green T-shirt and a wide smile. “Martin Richard was only 4 feet 5 inches tall and weighed 80 pounds,” said Weinreb, “so the bomb damaged his entire body.”

Of Dzhokhar, Weinreb said, “He believed that what he had done was something good. Something right. He believed he was in a holy war.”

A little less than an hour after Weinreb began, defense attorney Judy Clarke took the lectern for her response. Her manner was more folksy than Weinreb’s. Where the prosecutor had offered rat-a-tat facts, one gruesome reality after another, Clarke slowed down to speak to the jury as though they were having a coffee together. Like they were discussing a mutual friend who’d made a bad life decision.

“The circumstances that bring us here today are still difficult to grasp,” she said. “We’re going to come face to face with unbearable grief, loss, and pain caused by a series of senseless, horribly misguided acts carried out by two brothers—26-year-old Tamerlan Tsarnaev and”—here she gestured toward the young man sitting a few feet away at the defendant’s table—“his younger brother, 19-year-old Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.”

This was an unconventional opening argument. In her first paragraph, Clarke freely admitted her client’s guilt. “There’s little that we dispute,” she acknowledged of the government’s case. And then came a sentence you’ll very rarely hear from a defense attorney: “It was him.”

But Clarke then shifted gears, anticipating the jury’s confusion. “So you might say,” she posited, voicing the question they were no doubt now asking themselves, “’Why a trial?’”

The unspoken answer: Because this jury will decide whether Dzhokhar lives or dies.

Much earlier this morning, before the jurors were brought in, Judge George O’Toole had issued a ruling on the prosecution’s motion to exclude “mitigation evidence.” This means evidence that doesn’t speak to whether Dzhokhar committed these crimes, but rather evidence that helps to explain why he might have done it. Namely, that he was influenced and controlled by his radicalized older brother, Tamerlan.

The prosecution wants this first phase of the trial to be strictly about determining Dzhokhar’s guilt, which shouldn’t be a challenge. But the defense hopes to begin laying groundwork for the more important second phase, when the jury will decide (presuming they’ve already convicted Dzhokhar) whether to execute the defendant or to lock him up in a prison for life. Clarke’s specialty is to secure the latter fate for her clients no matter how diabolical their crimes. She’s successfully saved the lives of the Unabomber, Jared Loughner, Susan Smith, and Eric Rudolph—a pack of murderers who today sit in prison instead of on death row.*

Judge O’Toole granted the motion to exclude mitigation evidence, with some minor caveats. That didn’t stop Clarke from trying to slip in mitigation, wherever she could. Her strategy is evident: She hopes to humanize Dzhokhar for the jurors. And thus she showed them a photo of a cute, fresh-faced, tween Dzhokhar being bear-hugged by his much larger, more menacing, stubbled older brother. She suggested that while Tamerlan spent his time on the Internet “immersed in death and destruction and carnage in the Middle East,” Dzhokhar spent his time “doing things that teenagers do—Facebook, cars, girls.”

Though Judge O’Toole, sounding quite cranky, halted Clarke midsentence at one point to inform the jury that they will hear only “very limited evidence” regarding Tamerlan’s effect on Dzhokhar, Clarke ignored him and kept plowing along in the same vein. “Dzhokhar became vulnerable to the influence of someone he loved and respected very much,” she said. “He must be held responsible. But he came to his role by a very different path than the one suggested to you by the prosecution. It was a path paved by his brother.”

When opening statements concluded, the government’s presentation of evidence began. And we saw the shape of this first phase of the trial. In truth, both sides are already fighting over whether Dzhokhar should be killed or spared. The prosecution—while fulfilling its duty to prove Dzhokhar was culpable—will be mostly focused on painting Tsarnaev as a callous, evil monster. The kind of guy who shops for milk after he kills a little kid.

Along with photos and videos of the chaos, with blood and shrapnel and shredded limbs everywhere, the government presented the testimony of people who’d witnessed the hellscape. We heard from Shane O’Hara, the manager of a sporting goods store near the finish line of the race. “It was like a scene from Saving Private Ryan or Platoon,” he says of the moments after a bomb detonated, “something I never thought I would see in real life.” The prosecution played video from inside O’Hara’s store, showing people ripping T-shirts off the hangers to use as tourniquets and gauze. O’Hara admitted that, as the manager, he’d briefly worried about all the inventory, which brought a chuckle. But then he broke down on the stand. “There are things that haunt me,” he said. “Making decisions. Who needed help first, who needed more. That was never my role to make that decision, but you felt you had to do that.”

We heard from Rebekah Gregory, a woman whose leg—torn apart in the blast—was amputated just a few months ago, after 17 surgeries failed to repair it. She’d spent the week after the bombing in a medically induced coma. We heard from Karen McWatters, who lost not just her leg but her close friend, as she held Krystle Campbell’s hand while Campbell died. “I got close to her head and we put our faces together and we tried to talk to each other,” said McWatters on the stand. “And I didn’t see how bad her injuries were. She very slowly said that her legs hurt. And we held hands. And her hand went limp in mine. And she never spoke after that.”

Sydney Corcoran, a 19-year-old woman with long, dark hair, recalled waking up on the sidewalk in pain. “I remember a man putting his forehead to mine and telling me I was going to be okay and I just needed to hold on,” she said. “He was telling the people around him that I was going white. And I could feel my body getting tingly, and I was getting cold. And I knew I was dying.” She was brought to an ambulance with minutes to spare before she would have bled out. But she didn’t think her parents, who’d been standing next to her, had made it. “I thought I was an orphan,” she said, through tears. Her mother lost both legs, but both parents survived.

As all these people speak, and weep, sitting a few feet in front of Dzhokhar and facing him, I wonder what he has in his head. Judy Clarke once said of her clients, “They’re looking into the lens of life in prison in a box. Our job is to provide them with a reason to live.”

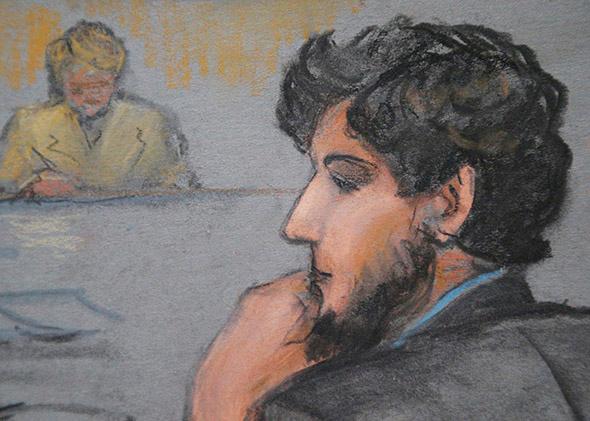

But for a man in those circumstances, Dzhokhar looks strangely unperturbed. He has a casual demeanor in the courtroom, wearing his collar open and two buttons undone. He taps his fingers on his attorneys’ binders to play imaginary piano chords. He leans back in his chair, and his feet waggle underneath the table. He smiles a fair amount during interstitial moments.

What goes through his mind as he sees this footage, and hears from these people who’ve lost limbs, who’ve lost friends, who feared they would die? Does he simply look at all these white Americans telling their sad tales and equate them to the woes of innocent, civilian Muslim victims of American bullets and bombs? Does he feel twinges of remorse, now that he’s forced to contemplate the residue of his actions in gruesome detail? Or does he spend his time wondering whether this jury will spare his life or put him to death?

When the day ended, Judge O’Toole reminded the jury not to discuss, read about, or give any thought to the case until they returned to the courthouse tomorrow morning. “There are plenty of other things to think about in your life,” O’Toole suggested.

Sure, I guess. But I find it impossible to believe that any of these jurors can clear their minds of the gory images they saw, or of the testimony they heard. And they haven’t even heard the worst of it yet.

*Correction, March 5, 2015, 12:13 a.m.: This article originally misspelled the moniker “Unabomber.”