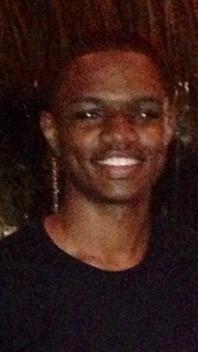

Earlier this month in Miami, Marquis Sams was gunned down in a drive-by shooting. You know the story, right? Chances are you’ve already assumed that the victim was young (correct) and black (correct). You may also have assumed that the murder didn’t take place in a quiet residential neighborhood (incorrect), and that Marquis was in a gang (also incorrect). It’s a comforting shortcut to pigeonhole the victims of the thousands of gun murders that take place in American cities every year. But in telling the story of my friend Marquis, I hope to flesh out how we often don’t understand the holes these victims leave behind, because we never had a sense of the spaces they filled.

Five years ago, Big Brothers Big Sisters matched up 15-year-old Marquis and me. He was just as tall and lanky back then, with the same bashful smile and loping stride. He comes from an exceptionally tight family from an exceptionally tight neighborhood. Miami is a new city teeming with transients and transplants, but Marquis’ family has been here longer than just about everybody. After several hours of playing basketball (he was generous enough not to dunk on me but not generous enough to let me win), I joked that there had to be some passer-by he didn’t know by name. “Nope,” he answered earnestly, “not one.” Later, walking through a nearby cemetery, I would pick out headstones and ask if this or that family was still around. Marquis would rattle off a couple of biographies and point to their houses.

Over the years, I’ve seen him go through a lot. I’ve seen him succeed as a promising basketball prospect at Coral Gables Senior High. But, when his brothers formed a band and their daily rehearsals conflicted with basketball practice, he gave up his hoop dreams to join them. That decision may have caused him pain, but never regret. They were his brothers, so it wasn’t even a question (wise call: they turned out to be quite good). I’ve seen him fail his last semester of high school—partially my fault, I’m not much of a tutor—but quickly recover to earn his diploma. And I’ve seen him learn with infinite patience how to drive, as I unnecessarily insisted that he parallel park over and over.

What I’ve never seen him do is curse, complain, or speak ill of anybody. When I used to tease him for regularly failing to go out on weekends, he would say, “Nah, man, I don’t want trouble.” He wasn’t much of a reader, but he was devoutly religious; when he did crack a book it was devotional or self-improvement. In the car, he would unselfconsciously start singing along to music he loved, from Mahalia Jackson to Michael Jackson. It didn’t take long to figure out that if he wasn’t singing along, it was time to put something else on.

Like a lot of twentysomethings, he didn’t know what the future held but was trying to get ready for it. At the time of his death, he was doing his best to make his way through college and working hard at a downtown restaurant to save money for his adored daughter. We’ll never get to see what he would’ve made of himself in the fullness of time, but it’s difficult to imagine his gentle kindness and dignified manner not making the world warmer.

After midnight on April 2, Marquis was sitting in his car talking to Wilneka Pennyman, 19, who was standing outside. A car pulled alongside and riddled Marquis and Wilneka with bullets. (I didn’t know Wilneka, but surely her loss is no less than Marquis’.) Wilneka took a few steps before she fell, but Marquis died instantly. The car was towed away with his body still behind the wheel.

Obviously the relationship between guns and murder is complex, and both sides of the gun control debate have interests that ought to be respected. But even as the murder rate drops, a black person in America is 10 times more likely than a white person to be the victim of a homicide involving a gun. For people Marquis’ age, the U.S. gun homicide rate is 43 times higher than the rate of 20 comparable countries. I’m not advocating particular policies, but it’s tough to argue that a nation so successful in championing human rights abroad can’t do a better job protecting its citizens at home.

Meanwhile a restaurant is without a server, a neighborhood loses a pair of helping hands, a congregation is deprived of a true believer, friends console themselves with memories, aunts and grandmothers are bereft of a beloved, brothers lose a beautiful voice, sisters get by with less support, a mother misses her son, and a daughter grows up without her father, who had quiet volumes to teach.

Most murders in Miami go unsolved, and it seems unlikely this one will be different. Last I heard Marquis’ death was simply a case of mistaken identity. His killers must have been looking for a much lesser man.