There is a problem with the South, in the way we tell the story of our past, and this problem has infected our country from sea to shining sea. All too often some incident reminds us of our murderous racial past and the hatred that has lingered for decades. Most recently we glimpsed this hatred in the church massacre in Charleston, South Carolina, but before that we saw it in the demonstrations in Baltimore, in the aftermath of the shooting of Walter Scott, the murder of Tamir Rice. Similar moments fill our news pages and television screens so regularly that the death of black people has become a kind of brutal heartbeat in our country.

Even when one of these moments of brutality takes place outside the states of the old Confederacy, like the murder of Michael Brown in Missouri, the shadow of renewed bigotry falls over the capitals and courthouses of the South, the place that our country sees—that has in fact earned its place—as the headquarters for racial hatred and white supremacy in America.

By the time you read this there may well be another such moment filling our newspapers and airwaves and laptop screens. It is inevitable that somewhere another black man will die in circumstances that look too much like a lynching to be ignored, and, because these acts now horrify us, we will move through the same stages of national hand-wringing as before. Once again we will hear pundits discuss the problem of race, which in our country is seen, whether rightly or wrongly, as a crisis native to the South.

I grew up confident, Caucasian, capitalist, in a 1960s South. In the South I knew, white people dictated the way that black people could live, where they could shop, what water fountains they could drink out of, and what bathrooms they could use. They were, after all, descended from savages, barely able to survive in the white man’s shadow. To my child’s mind, this was simply the way the world worked. The South is where I have lived all my life. Its history weighs on me more as I age and am able to see it more clearly, stripped of romance and myths of chivalry and charm. Stripped of confused nostalgia.

It is an inescapable truth that in the South the past is too much with us, late and soon, a statement that conflates two famous Williams, Faulkner and Wordsworth. In the Wordsworth poem, it is the world that is too much with us, as getting and spending we lay waste our powers. The quote is apt in that our old ways of getting and spending included a trade in human beings. In the South, slavery is the source of the evil that clings to the region, past and present, and as time goes by all other visions of yesterday are fading away. But still there are too many who have enshrined a different image of history, finding glory where none ever existed, then or now. And so to paraphrase Faulkner, in the South, the past has never lost its stranglehold on the present.

In the South we are doomed by history, especially by our failures, but we define these failures to our own advantage. We lost the war; we fell out of the golden age. We endured the humiliation of armed occupation. This is the lost cause of the South which white people talk about, and for a long time this was the only South that mattered to any of us. The South was a strange land where a bitter rebellion came and went, deeply painful for all sides. The conduct of the war and pain of those brief years overshadowed the reasons for the war, what it sprang from and what it meant. For decades white Southerners lived in the bitterness of that loss, until gradually it morphed into a victory of the spirit, and took on a kind of golden glow.

But what that glow disguised was the ever-deepening divide among both the races and among the classes within those races, as the poorer whites watched with increasing anger as the descendents of former slaves rose in the societal ranks, becoming successful in the very highest levels, with someone who looked like them even audaciously becoming president of the United States. And so many Southern whites wrapped themselves even more tightly in the myths of past glories and tattered traditions.

In the process, the reality of what slavery meant, the way it warped that old society, became obscured. Southerners could tell one another chapter and verse about Yankee armies, troop movements, the personalities of generals, the facts of battle. But the facts of slavery, the truth about our white brutality, about the system of terror that permeated the South for centuries, that sustained the idea of human property, became obscured, then romanticized, then lost.

It was all a lie, of course, but a lie of the sort that we live with every day. Far easier for white Southerners to believe that something was stolen from us than to understand that we, in the collective, shaped a terrible doom for ourselves in our insistence on holding human beings as property. Like Lady Macbeth, the creation of another famous William, we wander in delusion, attempting to wash away the blood that clings to our hands.

In the ignorance of my childhood, in the rural setting where I spent my first years, I accepted ideas about the place of white people at the top of the ladder, about the United States as a white country, that have stayed with me all my life. When I was a boy, I believed that as a white person I was part of the most advanced of all the races. I believed that my European ancestors were responsible for changing the world from a savage landscape into civilization. I learned these lessons far too young to question them, and this belief in white superiority is the foundation of the racism that was inculcated in me. White children today—in the South, but elsewhere too—are learning the same lessons, the same subtle and not-so-subtle lies, taught to them in the same way they were taught to me: by example, by inference, by insinuation, by myth.

It is too simple to assert that the South has not changed, that there has been no progress on these problems. At the same time, it is patently obvious that the South—that the whole country—refuses as much change as it accepts, and that it does so by some process that is neither rational nor governable. The white South is still a source of racist atrocities because many Southern whites have never wavered in their certainty that black people spring from an inferior race. For some of them—for some of us—that certainty will pass itself to the next generation.

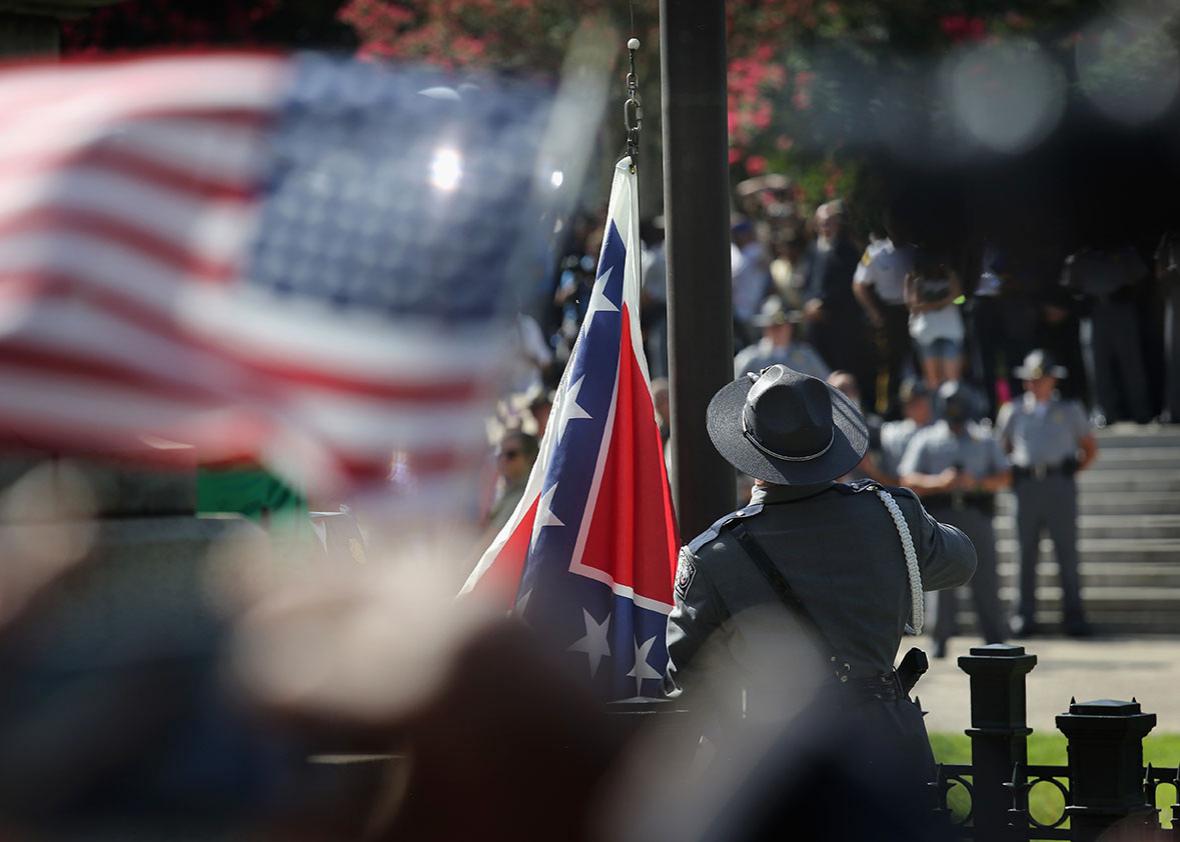

This debate often centers itself around that old symbol of the romantic South, the battle flag of the Confederacy that until finally overtaken by recent horrific crimes committed in its name still flew over Southern statehouses. Among people who see this rag of stars and bars as an odious reminder of our Southern delusion, this is a moment of hope.

But taking down the Confederate flag won’t change the landscape, of course, by more than a gesture. We need to look inside ourselves and see that the roots of this racial antipathy lie in all of us, and that it can rise to hatred in any of us. This is a hatred we promote without being aware of it, and share without admitting it, and we must learn to see that. Otherwise, blind to the truth about ourselves, we will raise another generation in which a white race warrior buys a gun, walks into a room full of black people, and soaks his hatred in their blood.

If the past refuses to resolve itself, at least part of the reason for this persistence is that we refuse to see it for what it was. But maybe we can open our eyes.