For a man who has reported from actual war zones and disaster sites, Wolf Blitzer is easily spooked by a bunch of dudes stealing stuff from an urban pharmacy. As CNN aired wide-angle footage Monday of nonchalant looters entering and exiting the chain drugstore near North and Pennsylvania avenues in Baltimore, Blitzer described the scene like it was the fall of Rome: “This is a picture of a CVS pharmacy, and casually people are just going in there—they’re not even running—they’re going in there, stealing whatever the hell they want to steal in there, and then they’re leaving, and they’re … I don’t see any police there. Where are the police?”

Where are the police? was the theme of CNN’s coverage of Monday’s riots in Baltimore, riots that began after the funeral that day of Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old black man who had died a week earlier after suffering an unexplained spinal injury while in the custody of the Baltimore Police Department. The theme ran through Blitzer’s sustained shock at the brazen drugstore looters. It underpinned Don Lemon’s surprise that the mayor and governor had not summoned the National Guard on Saturday, after protesters visited Baltimore’s Inner Harbor neighborhood and interrupted fans’ egress at the Camden Yards baseball stadium. Where are the police?—implicit in that question is the assumption that the police are the solution to social unrest, rather than agents of it.

Credulous, deferential statism is the soul of cable news, and CNN will never be something that it isn’t. But what it is seemed particularly out of place in Baltimore on Monday night, especially given these riots’ thematic similarity to the protests and unrest that followed the police-assisted deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in Staten Island. “It’s hard to believe this is going on in a major American city right now,” Blitzer said of the looting and riots in Baltimore. Well, no, it wasn’t hard, actually. If “this” means unrest over the unnecessary death of a young black man as an illustration of perceived systemic police brutality, then “this” has dominated cable news for much of the past year. America’s underclasses are not on particularly good terms with their local police departments these days, and if any news outlet should be aware of this, it’s CNN, given the network’s omnivorous coverage of the Brown and Garner stories.

So why is that coverage so consistently unsatisfying? CNN, like all televised media, specializes in nearsighted news, favoring big, easily apprehensible images and storylines. The limitations of the format often demand one central visual narrative, to which the reporting and commentary act in service. Burning cars and looted buildings are big, striking images that play well on television, but they too often end up reducing complicated issues to stories about property damage. If it sometimes seemed Monday as if CNN expected Baltimore to burn, that’s understandable: CNN mostly just sees the things that are already on fire. (Often quite literally: On Monday evening, for example, the network focused much of its coverage on an actual three-alarm fire at a half-built Baltimore senior center. After a certain point, there is very little news value that any reporter can add to a story about a fire beyond just continuously reiterating that, yes, the building is still on fire.)

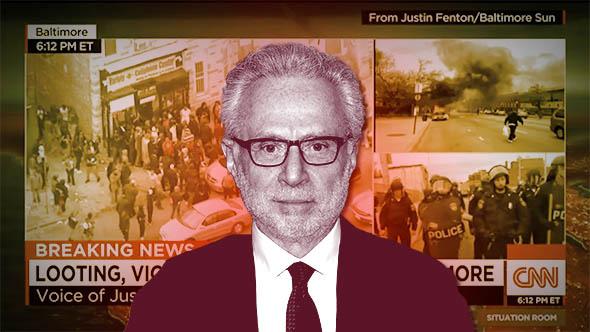

Screenshot via CNN

There was violence in Baltimore on Monday, plenty of it. Baltimore is a big city, and much of it was untouched by the riots and looting, but it would be disingenuous to claim that the actual damage was meaningless. Some local leaders expressed frustration that the media coverage was wholly focused on isolated pockets of lawlessness while ignoring the many peaceful protests happening at the same time. While I understand their frustration, I can’t fault the media for emphasizing the riots. Like it or not, “if it bleeds, it leads” is how journalism works, and that’s not necessarily a flaw. If it bleeds, it’s generally important, too.

But good journalism also tries to understand why a city is bleeding instead of just frowning at the wound. (Or fitting it into a script that was written in Ferguson.) I spent Monday afternoon and evening riveted to the Twitter feed of the Baltimore Sun crime reporter Justin Fenton, who spent what seemed like a harrowing couple of hours near North and Pennsylvania avenues watching looters and rioters invade shops, menace passing cars, and attack bystanders. (Wolf Blitzer did have Fenton on Monday to discuss the looting; it was a good segment.) Fenton, on Twitter, also wondered where the police were, and why they weren’t doing more to stop the violence. “I’m not second-guessing police tactical decisions. But the overwhelming sense out there was that people were doing this because they could,” he wrote. Fenton came to this observation through on-the-ground reporting, and was able to add layers of nuance to a scene that, from the sky, just looked like a bunch of undifferentiated angry people throwing rocks and stealing diapers. In his evening story for the Sun, co-written with Erica L. Green, Fenton added the sort of context that the networks could have used more of. “These kids are just angry,” a community leader told the paper.* “These are the same kids [the police] pull up on the corner for no reason.”

Where are the police? In West Baltimore, they’re usually everywhere, apparently, just like cops are in most poor, black urban neighborhoods: engaging in the sort of zealous pre-emptive policing that can easily engender community resentment. In a story in last week’s Baltimore City Paper, reporter Edward Ericson Jr. spoke to several Baltimore residents and former Baltimore police officers to get a sense of the policing context in which Freddie Gray died. His interviewees all spoke from personal experience to describe a police department that allegedly allows its officers to freestyle. “Routine violations of the General Orders—the policy bible that all officers are supposed to follow to the letter—beget sloppy policing and a culture of callous laxity,” wrote Ericson. “The General Orders are just the first thing to fall.”

Again, that’s good reporting, and good context. But context is hard to come by if you report in isolation. At the top of his piece, Ericson reported on the CNN encampment, and the fact that the network had engaged its own security guards, “five beefy white guys … hired to protect the national reporters from the neighbors of West Baltimore.” That’s Ericson’s observation, and I don’t mean to imply that CNN’s correspondents, producers, and crew have not taken risks in pursuit of their stories. But the security-guard anecdote illustrates a larger point: that no matter how neutral it tries to be, CNN cannot help but operate from a standpoint of us and them. In case you can’t tell from its roster of celebrity contributors, its anchors who appear on Celebrity Jeopardy!, and its political talk shows that aren’t deferential so much as they’re knowing, CNN is and always will be us.

Where are the police? When the Sun’s Fenton asks that question, it reads like an actual question. When CNN asks that question, it sounds like what the network really means is: We need more police! And that’s not the right answer at all. More police on the streets might quell these particular riots, but it’s a tactic that will likely just serve to reinforce the difference between us and them.

A little more than two years ago, on April 19, 2013, I was in the Boston area covering the citywide manhunt for Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. The streets of Boston were deserted that day by mayoral request, except for the swarms of cops who arrived in armored vehicles from around the state, and the Watertown residents who had been briefly expelled to the sidewalks as SWAT teams went from house to house looking for Tsarnaev. I remember walking to my car after filing a story from the field and being accosted in the parking lot by an aggressive, well-armed police officer who demanded that I explain who I was and what I was doing there, and seemed more than willing to throttle and arrest me if I failed to do so to his satisfaction. About 30 minutes earlier, one displaced Watertown resident, straddling a bicycle, had talked to me of the philosopher Slavoj Žižek, and his contention that the most significant consequence of terror attacks isn’t the actual human or financial casualties—which are always relatively minor—but the creeping normalization of the security state. “In the end, three people died because of the [Boston Marathon] bombing,” the man told me at the time, as police officers in military-style apparel went, warrantless, from house to house, looking for someone who wasn’t there. “But the real result is that we become acclimated to stuff like this.”

On Monday the city of Baltimore lost a CVS and some other stores, buildings, and police cars. While the losses are undoubtedly deeply felt by the respective shopkeepers and landowners, they are not significant losses in absolute terms. These stores are presumably insured. The Police Department will eventually get replacement cruisers. There are other pharmacies, and shopping malls.

On Tuesday the city of Baltimore institutes a weeklong 10 p.m. curfew, and a reported 5,000 additional cops will flood the city streets. And CNN will continue to report as if a looted CVS is the main problem.

*Correction, April 29, 2015: This article originally misstated that a community leader told the Baltimore Sun’s Justin Fenton, “These kids are just angry.” Fenton’s colleague Erica L. Green collected the quote. (Return.)