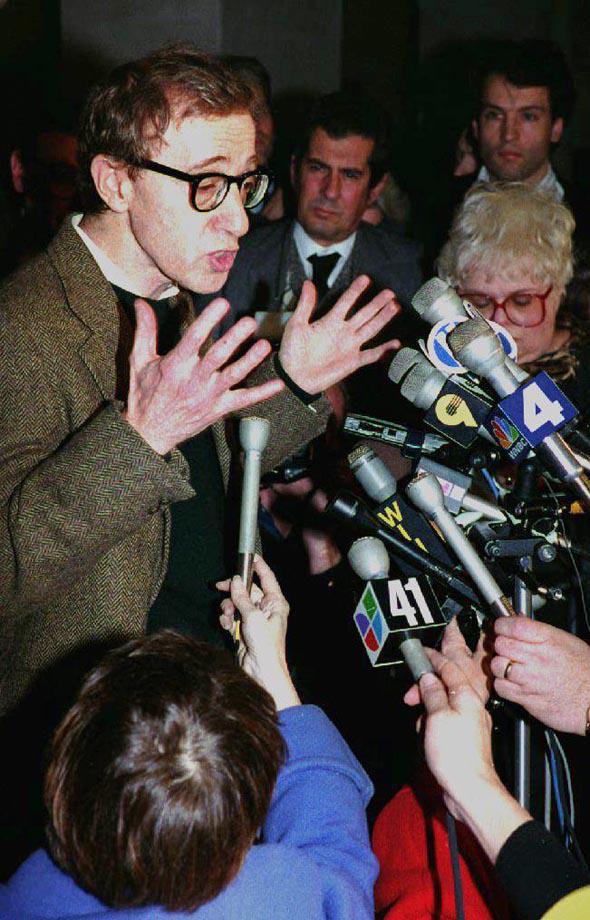

For more than 20 years, any and every new Woody Allen movie has provided occasion for handwringing over the director’s personal life: his ghastly 1992 split from Mia Farrow; his affair with Farrow’s college-age adopted daughter, Soon-Yi Previn (whom he later married); and worst of all by far, there were the allegations that Allen molested the daughter he adopted with Farrow, 7-year-old Dylan.

The heat of controversy has recently intensified around Allen, who just earned his 24th Academy Award nomination for his latest film, Blue Jasmine, which also got nominations for actresses Cate Blanchett and Sally Hawkins. In November, Vanity Fair published Maureen Orth’s revisitation of the Allen-Farrow scandal, including the first-ever media interview with Dylan. The interview was a bombshell: Dylan (who now uses a different name) did not waver from the story she told at age 7 about Allen molesting and sexually assaulting her in the attic of her mother’s home in Connecticut, on Aug. 4, 1992. On her side is her brother, media-star-in-the-making Ronan Farrow. After Allen received a lifetime-achievement award at last Sunday’s Golden Globes ceremony, Ronan tweeted, “Missed the Woody Allen tribute—did they put the part where a woman publicly confirmed he molested her at age 7 before or after Annie Hall?”

So what should an outside observer make of the Allen-Farrow debacle, two decades after the fact?

Allen’s defenders have always had one simple fact on their side: He has never been charged with a crime, much less convicted. What we know is that in August 1992, Farrow and Dylan visited Dylan’s pediatrician, who then contacted authorities about an abuse allegation. The Connecticut state attorney later asked the Yale–New Haven Hospital Child Sexual Abuse Clinic to evaluate Dylan. In March 1993, the clinic “concluded that Dylan had not been sexually abused,” according to Orth in Vanity Fair.

Case closed? Not necessarily. Three months later, that June, Acting Justice Elliot Wilk of New York State Supreme Court ruled against Allen in his effort to wrest custody of his three children from Farrow. Wilk criticized Yale–New Haven’s findings, stating that the hospital’s team declined to testify at trial except via deposition by team leader John Leventhal and destroyed its notes on the case; a 1997 Connecticut Magazine piece pointed out that Leventhal had never interviewed Dylan.* In her first piece for Vanity Fair about the Allen case, published in 1992, Orth had at least 25 on-the-record interviews—with sources both named and unnamed—attesting that Allen was “completely obsessed” with Dylan: “He could not seem to keep his hands off her,” Orth wrote.

In his June 1993 ruling, Wilk also denied Allen any visitation rights with Dylan or his older adopted child with Farrow, 15-year-old Moses. In May 1994, in a hearing considering custody or increased visitation for Allen, the Appellate Division of the state Supreme Court cited a “clear consensus” among psychiatric experts involved in the case that Allen’s “interest in Dylan was abnormally intense.”

In Allen’s defense, he and his lawyers held that Farrow, enraged by her discovery of Allen’s affair with Soon-Yi, may have manipulated Dylan into making the allegations: “Mr. Allen specifically denies the allegations that he sexually abused Dylan,” the appellate court wrote in 1994, “and characterizes them as part of Ms. Farrow’s extreme overreaction to his admitted relationship with Ms. Previn.” In a Time magazine cover story in 1992, Allen said, “The atmosphere up there in Connecticut is so rife with rage against me. So it’s possible this emerged from that. But it also could have been made up intentionally.”*

In strictly general terms, such a hypothesis is not far-fetched. “It’s a frequent occurrence that allegations of child molestation emerge at the time of either a breakup or a custody dispute,” says David Finkelhor, a professor at the University of New Hampshire and the director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center. “Some people will be trumping up a charge to try to turn the conflict in their direction or get sympathy for their claims.”

But Finkelhor, again speaking generally, also makes the case for an entirely different scenario. “In other cases, people will make claims about things that they were willing to look past or that children were keeping under wraps for fear of breaking up the family,” he says. “These things will come out at the time [of a divorce or custody battle], because then they feel more freedom to articulate them. … The consequences of realizing that intra-family sexual abuse is going on are so devastating that it’s not uncommon for people to overlook it or explain it away.”

In the Time interview, Allen strongly suggests a cause-and-effect relationship between Farrow discovering his affair with Soon-Yi and the molestation allegations. But that account is hard to deduce from the timeline of events. Farrow found out about the affair when Allen left pornographic photographs of Soon-Yi on his mantel in January 1992—eight months before Dylan made her allegations. By Orth’s account, Allen was already in therapy for “inappropriate behavior” with Dylan before the revelation of the affair.

And in their May 1994 decision, the judges of the New York appellate court held that, with regard to the events of Aug. 4, 1992, “the testimony given at trial by the individuals caring for the children that day, the videotape of Dylan made by Ms. Farrow the following day and the accounts of Dylan’s behavior toward Mr. Allen both before and after the alleged instance of abuse, suggest that the abuse did occur.” Although “the evidence in support of the allegations remains inconclusive,” the court stated, “our review of the record militates against a finding that Ms. Farrow fabricated the allegations without any basis.”

By speaking out now, Ronan Farrow and the former Dylan Farrow have put Allen’s alleged actions under a harsh spotlight for the first time in a generation. But while their statements may have shaken the live-and-let-live consensus that formed around Allen not long after the scandal broke, they’ve hardly shattered it. That consensus is especially robust in Hollywood, where Allen is likely Western society’s most prominent beneficiary of compartmentalization. A-list actors never stopped clamoring to work with him, not even in the 1990s, and never will. At times during the Golden Globes tribute to Allen, it seemed hard to spot anyone toward the front of the room who hadn’t been in one of his movies.

Strangely enough, a similar kind of compartmentalization is one of the major themes of Blue Jasmine. In her Oscar-nominated role, Cate Blanchett plays the title character, the wife of a crooked financier. So long as her marriage is sailing smoothly, Jasmine waves away all suspicions about her husband’s incredibly lucrative business dealings; it’s only when she discovers his affair with their teenage au pair that she calls the FBI in a fit of vengeance. So Jasmine does what she does for the wrong reasons, perhaps—but her hunch turns out to be right. It’s a big, juicy, hyper-dramatic scene. Maybe the Oscar producers will show that clip when the Best Actress award is announced on March 2.

Correction, Jan. 17, 2014: This article originally misquoted Woody Allen as saying that the atmosphere among Mia Farrow and her children was “so rife against me.” He actually stated that it was “so rife with rage against me.” (Return.)

Correction, Feb. 3, 2014: This article also originally misstated that the Yale–New Haven Hospital Child Sexual Abuse Clinic never interviewed Dylan Farrow; it should have said that the head of the hospital’s investigating team, John Leventhal, never interviewed Dylan. (Return.)