Let the Fire Burn, Jason Osder’s powerful debut documentary, opens with period footage of a soft-spoken boy with two names: Michael Moses Ward and Birdie Africa. Michael was known as Birdie as a child—he was one of several kids raised by a small black liberation group that occupied a Philadelphia row house on Osage Avenue. They called themselves MOVE, and they wanted to live without technology and without government interference. But the group and the city were constantly at odds.

On May 13, 1985, the enmity between MOVE and city officials erupted into one of the worst days in Philadelphia history. Years of demonstrations, clashes, and arrests had finally culminated in a mass eviction order and an hours-long shootout. When the shooting ended in a stalemate, the city made the unthinkable decision to drop a bomb on the MOVE row house. It ignited a raging fire. Michael and one other MOVE member escaped, but 11 others were killed, and 61 homes burned down—a working-class black neighborhood turned to ash.

I’m a year older than Michael Ward, and I also grew up in Philadelphia. I remember watching that terrible fire burn, though I was seeing it on TV, safe in my house in a different part of the city. I remember feeling sad, scared, and confused. My father had campaigned hard for Wilson Goode, who’d been elected as Philadelphia’s first black mayor a year and a half earlier. How could Goode have stood by while the police dropped that bomb, and as that fire burned?

It’s to the credit of Osder’s film that it answers these questions by gradually zeroing in on them. Let the Fire Burn offers an even-handed depiction of the racial conflict that led to the conflagration on Osage Avenue. A 1976 re-election ad for Frank Rizzo, the previous mayor, who had built his reputation by raiding the Black Panthers, called Philadelphia “tortured” and complained that “abandoned homes pockmark the ghetto.” The racism was barely below the surface. MOVE’s extremist views are fully aired in the film, too. In one piece of old tape from the 1970s, a group of small MOVE children, naked and dreadlocked, chant mantras like “Our religion is non-compromising to the conception of insane speculation.” The adults also come across as caring, though. “They didn’t believe in spanking,” Michael says in a deposition taken five months after the fire.

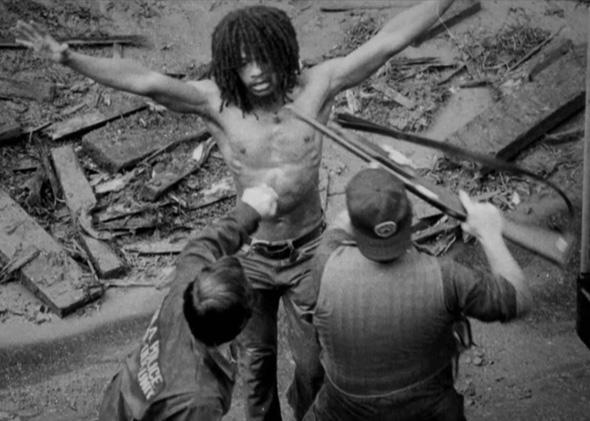

During Rizzo’s tenure, the police department made nearly 200 arrests of MOVE members, often for small street demonstrations. In 1976, six cops were injured in a scuffle with the group that somehow—the details are hazy—caused the death of a 3-week-old baby, Life Africa. After that, it was war. Rizzo promised in 1978 that the police would drag the MOVE members out of their compound “by the back of their necks.” The city turned a huge hoselike weapon called a “deluge gun” on the MOVE house. The confrontation spun out of control, shots were fired on both sides, and a police officer was mortally wounded. Nine MOVE members went to prison for killing him. But when three cops were prosecuted for viciously kicking and beating MOVE member Delbert Africa on the sidewalk—an assault caught on camera—they were found not guilty.

This may sound like a sadly typical-of-the-period case of black extremists versus white city establishment, but it wasn’t that simple. Osder shows that the people complaining the most about MOVE were the group’s neighbors—“ordinary black people,” in the words of City Councilman Lucien Blackwell. By the time Goode was elected in 1983, MOVE had become the scourge of the block. Late at night, loudspeakers blasted curse-laden diatribes from the house. MOVE men walked the sidewalk carrying rifles. They built a fortified rooftop bunker with slits for weapons. “They decided to aggravate the neighbors to force the city’s hand,” a negotiator who tried to work with both sides says on camera.

Goode, a former managing director of the city and a leader of its black middle class, identified with the decent folk being woken by the loudspeakers and spooked by the guns. The mayor promised to seize control of the MOVE house “by any means necessary,” the irony of invoking Malcolm X apparently lost on him. The city drew up eviction warrants. Then-District Attorney Ed Rendell (later Pennsylvania’s governor) piled on indictments for disorderly conduct, parole violations, and criminal conspiracy. On May 13, 1985, the police prepared to execute the warrants, telling the residents of the block to evacuate for 24 hours. “Attention MOVE, this is America,” Police Commissioner Gregore Sambor called into his bullhorn as the police lined up outside the row house.

Screenshot courtesy of Zeitgeist Films/George Washington University

The cops blasted water and tear gas to roust the MOVE activists. They fired 10,000 rounds of ammunition. The house and bunker stood, and no one came out. Late in the day, Sambor sent a Pennsylvania state helicopter to drop onto the roof two 1-pound bombs made from a mixture of explosives. The TV cameras were there for all of it, and the clips Osder includes seem as crazy now as they did then. The bombs land. Smoke rises. Flames spread. TV anchors say they can’t believe what they’re seeing. Five children were among the 11 MOVE members killed. The people of Osage Avenue watched their homes go up in smoke.

Testifying before the commission that later investigated the MOVE disaster, Goode said that at 6 p.m., half an hour after the bombs were dropped, he called Sambor and ordered him to put the fire out. The fire commissioner testified he never received that order. I believed Goode, though maybe that’s because I wanted to. I could accept that the city was dysfunctional, but didn’t want to think Goode would let a whole neighborhood burn.

At the time of the MOVE fire, my father, Richard Bazelon, was chair of the Redevelopment Authority of Philadelphia (a volunteer position he got as a lawyer who represented Goode’s campaign on voter registration and Election Day issues and did other community work). I called my father to talk about Osder’s film, and he reminded me that the aftermath of that awful night was also sad, though in a different way.

Mayor Goode wanted a black developer to do the reconstruction. The absence of minority developers on city projects was stark, and accomplishing the rebuilding in a way that addressed that problem offered the promise of making some good come out of the tragedy. The city chose Ernest Edwards, who appeared to be a promising minority developer, but one who had not undertaken a project this big before. The mayor “turned down offers from developer Willard Rouse III and the Philadelphia Building Trades Council to do the job at cost,” according to John F. Morrison in the Philadelphia Inquirer. The $6.5 million budgeted for rebuilding swelled to $31 million, yet, despite the high cost, it soon became clear that the new houses were poorly constructed and riddled with defects—plumbing leaked and wiring failed. In May 1987 a grand jury blamed some of the cost overrun on the negligence and mismanagement of city officials. Edwards was convicted of stealing $138,000 and served about seven years in prison.

The Osage blocks never recovered from this double blow. In 2010 Morrison reported that 17 houses were boarded up and 18 more were abandoned.*

That’s one sorrowful coda to Osder’s film, though he doesn’t explore it. Here’s another, which happened too recently to make it into the movie: Last week, Michael Ward died at the age of 41, after being found unconscious in a hot tub on a cruise ship vacation. He’d gone to live with his father after the fire, recovered damages from the city, served in the Army, and worked as a truck driver.

Though Osder’s movie doesn’t include these final chapters, it does enough—more than enough—to remind us both of how hard it is to live next to armed radicals, how disastrous it is when the government lets itself be baited into unleashing all of its might against them, and how racially charged the city was so recently. It was a relief, when the movie ended, to think of how much better Philadelphia is faring these days as a city than it was then. I’m not sure it’s found urban peace or racial harmony. But it’s closer.

*Correction, June 13, 2014: This article originally misstated that John F. Morrison is a reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer. He is a reporter for the Philadelphia Daily News. (Return.)