India’s tallest buildings, the missile-shaped Imperial Towers, rise up through the smoggy haze of the nation’s financial capital, Mumbai, like a shimmering vision of Oz. The most dramatic view of the towers comes from gazing at them down Falkland Road, a diagonal avenue that cuts through the heart of the island metropolis and dead ends right before the buildings. But the luxury high-rises’ promotional photographs never show this view because, to Mumbaikars, Falkland Road is synonymous with prostitution and is best known for the infamous cages that display the human merchandise. On Falkland Road, rates for services begin at $1; just up the street, in Imperial Towers, the penthouses go for $20 million. The economic vertigo is even more intense than the actual vertigo one gets staring down at Falkland Road from the penthouse balcony.

Mumbai has long been famous for the cheek-by-jowl existence of some of the world’s richest and poorest people. In the decades since India’s independence, impoverished squatters have been filling in any unused space in the megacity, and courts and politicians have generally protected their right to stay. But in the last decade, a new generation of luxury developments has been built atop transformed slums like the shantytown that once sat on the site where Imperial Towers now rises. They are the products of a land policy reform that allows real estate developers to build market-rate projects atop former slums provided they rehouse the slum dwellers on site; though it is easy to miss, next to the tall, flamboyant Imperial Towers sits a cluster of midrise slabs. The results are often surreal, but Mumbai’s slum redevelopment program may have repercussions far beyond India. The city is providing a real-world test of Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto’s theory that the best way to fight poverty in the developing world is to give slum dwellers legal title to their property. But not everyone sees it as a solution to the multifaceted problem of developing world poverty.

The Mumbai slum redevelopment policy is the brainchild of local starchitect Hafeez Contractor, who is not coincidentally the designer of Imperial Towers. “I used to always say something should be done about the slums. And I always used to say that the best way of [dealing with] slums was that you give them free houses, keep the land, and build on it and make money,” Contractor told me when we met in his office near the Mumbai stock exchange. “When I first told them in 1982 … everybody said I am crazy. Today, they are implementing it.”

In 1995, with the backing of the populist local power broker, Balasaheb Thackeray, Contractor’s plan was approved. “Whatever you might say, Balasaheb had balls of steel,” Contractor said of the controversial figure, an open admirer of Hitler, who died last year. “All credit should be given to him.”

With the policy framework in place, as the Mumbai economy has boomed in the new century, the slum-dotted landscape has been transformed. Increasingly, slums in prime locations, like the one near the Mumbai international airport chronicled in Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers, have become the site of negotiations between residents and developers. The law specifies that if 70 percent of a slum’s residents approve, the land can be redeveloped in exchange for each family being given an on-site apartment of 270 square feet. (Rumors that developers trade cash bribes for votes are rampant in the city.)

When I visited the Imperial Towers site with a group of U.K.-based architects, a family of four welcomed us into their tiny two-room apartment—one room for sitting and sleeping and the other, a kitchen-cum-bathroom, for everything else. The mustachioed man of the house, who wore a white undershirt that clung to his burgeoning potbelly, showed the place off with pride, though each room was not much bigger than the parking spaces in the multistory lot reserved for the millionaires next door.

The architects were less impressed. The group was universally shocked that these filthy buildings, with their dark and dirty hallways and water stains beneath the windows from drying laundry, had been built so recently. In both style and upkeep, they resembled the crumbling 50-year-old slabs that ring former East Bloc cities like Bucharest, Romania, and Ljubljana, Slovenia. In theory, one of the benefits of legalizing and formalizing the slum is to get slum dwellers to pay for the electricity they were formerly stealing from the city and connect them to the municipal water system. But because the policy calls for rehousing the poor without doing anything to raise their incomes, many end up unable to pay for utilities or contribute to the upkeep of the buildings through residents’ association dues. And the authorities lack leverage to get residents to pay their dues even when they can; this is a system that couldn’t evict the tenants when they were brazen squatters.

Courtesy of Daniel Brook

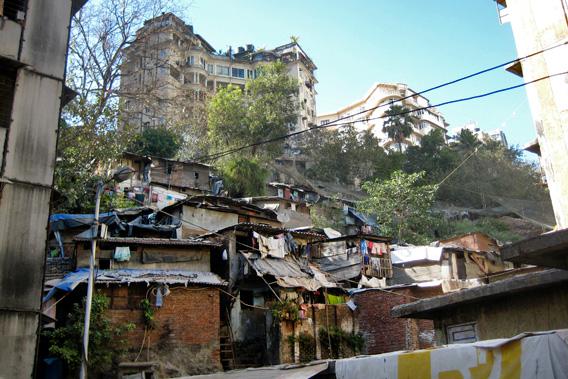

As we toured the lone snippet of shantytown that had yet to be transformed into rehousing slabs, one architect noted that for all the poverty of its conditions, with only makeshift electricity connections and no running water, the village-like settlement that clung to the hillside reflected the organic urbanism humans built for centuries before being upended by the high modernist dream of housing people more “efficiently” in boxes. As I chatted with him, careful to avoid stepping into the development’s open sewer, this sounded like a sentimentalization of poverty. But when I later spoke with Mumbai urbanist and author Naresh Fernandes, he noted, “We’re just beginning to stack up the poor in high-rises while Chicago’s just demolished all of its high-rise projects.”

As for de Soto’s larger theory about the benefits of giving the poor title to the land on which they’ve previously squatted, the test results have yet to come back, as the slum redevelopment regulations don’t permit rehoused slum dwellers to sell their apartments until they’ve lived in them for 10 years. At that point, residents will face a choice of whether to part with their centrally located apartment and purchase a larger one farther from the center of the city or perhaps use the apartment as collateral to take out a small business loan. Even if the program ultimately vindicates de Soto, there is a limited universe of cities in India or elsewhere in the developing world where such projects could be built. The program is predicated upon the fact that Mumbai is a global financial and entertainment hub built on an island where, for all its poverty and problems, the land is worth billions. For the numbers to add up, the high-end developments need to be high-end enough to pay for the low-end rehousing apartments. This approach wouldn’t work in second-tier Indian cities like Nagpur or in cities in less economically dynamic developing countries like, say, Managua, Nicaragua.

At the Atria Mall, a slum redevelopment where the developer has opted to build upscale retail, twin dealerships for Rolls Royce sedans and Ducati motorbikes greet entering shoppers. Inside, stores for global brands including Swatch and Samsonite share air-conditioned space with local boutiques, among them a jewelry shop called Bling. Behind the building, a high wall plastered with billboards for upscale watches and other luxury goods obscures the telltale water-stained high-rises. I slipped through a gateway to find piles of garbage swarming with flies and lying against the backside of the wall; despite the city’s far-reaching slum redevelopment policy, it has yet to build a comprehensive sanitation system. The sewage stench called into question the quality of the municipal wastewater system to which the city aspires to connect its reconstituted slums.

Does the slum redevelopment program actually solve the city’s problems, or does it just hide them behind walls plastered with ads for luxury goods? When I told one of the city’s leading urbanists that I was heading to the Atria Mall, which she knew well from shopping, she looked puzzled. “Atria’s a slum redevelopment? I had no idea.”