John Martorano is a porpoise of a man inside a massive suit jacket. His face disappears into the fat of his neck. When he takes the stand today—tinted eyeglasses, polka-dot tie, pocket square—he tells us he is 72 years old, divorced, and unemployed. Also, he has murdered 20 people.

Martorano discusses these killings as though he’s reading from a phone book. He’s rehashed his criminal résumé for prosecutors countless times before and now seems genuinely bored of his own story. At one point, he checks his watch, his heavy breathing reverberating through the courtroom microphone.

“And what happened then?” the prosecutor repeatedly asks at he leads Martorano through a litany of carnage—to which Martorano will respond, with a phlegmy grunt, “I shot him” or “I took his knife from him and I stabbed him” or “I left the body in the trunk.” When asked to explain where he shot one victim (I’d thought the answer might be something like “the HoJo’s in Dorchester”), Martorano says, “in the heart.” There is no change in his expression or vocal inflection.

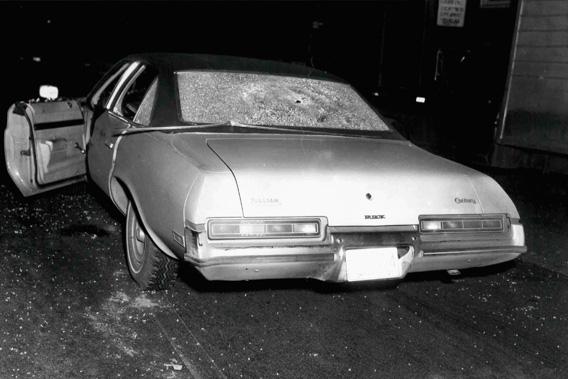

U.S. Attorney’s Office/Handout via Reuters

Shockingly, Martorano strolled into the courtroom today a free man. He confessed to those 20 murders, but his plea agreement got him sentenced to 14 years. He only ended up serving time from 1995 until 2007. It’s almost unfathomable that a coldblooded killer like this is walking the streets. The government was so consumed with nailing Whitey, it was willing to cut this monster a break.

Martorano doesn’t see it that way. The only time he shows any sort of emotion is when he describes his relationship with Whitey, and Whitey’s longtime accomplice, Stevie Flemmi. “They were my partners in crime,” says Martorano. “They were my best friends; they were my children’s godfathers.” Martorano even named his son James Steven after them. It was only when he learned that Bulger and Flemmi had been FBI stool pigeons that Martorano decided to roll over and testify against them. “After I heard they were informants, it sort of broke my heart,” says the fleshy psychopath. “It broke all trust we had. All loyalties. I was just beside myself with it.” You get the sense he was not beside himself when he repeatedly shot innocent bystanders, or assassinated an honest businessman. But this was different.

We’ve met three kinds of people so far in this trial: cops, bookies, and killers. If you ask me which I’d choose to have a beer with, I think I’d go with the bookies. They’ve got great stories and a splash of mischief in their eyes. Both James Katz and Dick O’Brien—the two elderly bookmakers who’ve taken the stand here—come across as semi-decent fellows who entered a semi-unsavory profession. They were never violent. They were always vulnerable. Even now, safe in a courtroom, their terror is palpable as they describe how frightened they were of the gangsters who were forever extorting them.

The cops (that is, the upstanding cops who’ve testified so far) hold the moral high ground over the bookies. But they are hard men, in their own way. Years of fighting scum like Martorano has made them callous. Last week, we heard a passage from State Police Col. James Foley’s book. Martorano got a toothache while Foley had him in custody, so Foley took him to a dentist—and then frightened the dentist for jokey kicks. “This guy’s up from Florida,” said Foley by way of introduction, requesting treatment for a cavity. “Probably killed 30 or 40 people. I don’t know if any were dentists!”

On the witness stand, Foley explained his jaunty tone with a defense along the lines of “I don’t think we need to be 100 percent serious at every moment.” I wholeheartedly agree. But others might not. How do victims’ families, some sitting here in the courtroom, process a wisecrack like this? When the subject is murder, is there any room for levity?

I’ve done my share of lighthearted joshing as I report on this trial. Other journalists who cover Whitey seem prone to adopting a sort of tough-guy patois—as though they themselves were in the middle of the action. Either way, we are all here less for the news value of the proceedings (these crimes happened decades ago and have no wider impact on the world) than for entertainment. Just like the people behind the slew of books written about Whitey. Or the people trying to make Hollywood movies about him. True crime sells.

It has for Martorano. He sold the film rights to his life story for $250,000 and will get even more if the movie’s ever made. He raked in another $75,000 or so by cooperating on a book with Boston newspaper columnist Howie Carr. The book is called Hitman, but Martorano says that label is all wrong. A hitman kills people for money, something he says he’s never done. He says Carr chose the title because “he thought it would sell better.”

Tomorrow morning, Martorano will resume his testimony. We’ve only made it about halfway through the list of people he’s killed.