For the third straight day, blubbery Boston mob enforcer John Martorano perches on the witness stand, befouling the courthouse with his presence. For the second straight day, defense attorney Hank Brennan attempts to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Martorano is a demonic sociopath.

Brennan is not a guy you want asking you questions for hours at a time. With his pinched face, pinched voice, and talent for feigning altar-boyish shock, Brennan has the air of that kid on the fourth-grade playground who’s caught you in a lie and will never, ever let it go. To be sure, he’s smart and relentless. But I would guess a large part of his talent lies in his ability to irritate adversarial witnesses until they lose their cool.

That said, there’s no one I’d rather see squirm than John Martorano. Brennan’s first mission Wednesday is to paint Martorano as a man prone to lying. Implicit suggestion: If he’s lied in the past, Martorano might well be lying to the jury right now.

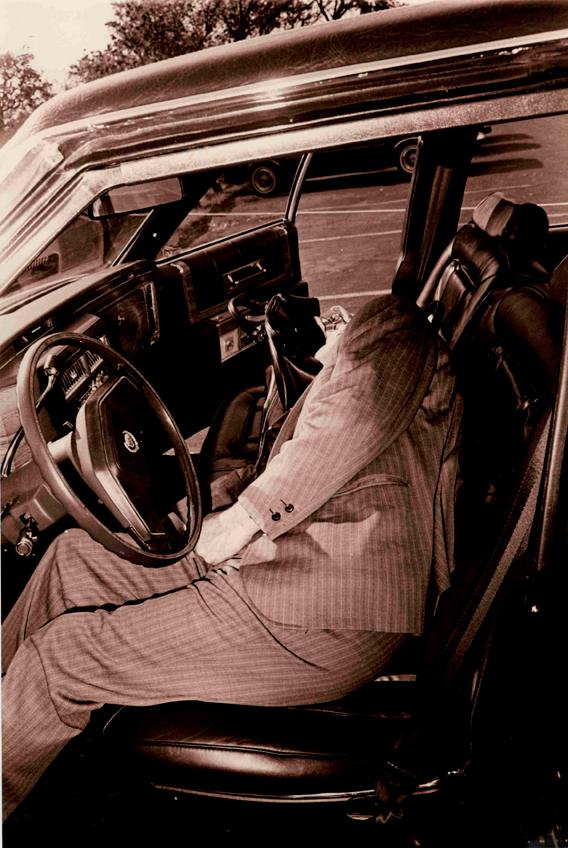

Brennan asks if Martorano told the truth to his friend John Callahan when he lured Callahan to Florida, and then into a van (a van custom-fitted with “captain’s chairs,” Martorano noted Tuesday for some reason I can’t fathom), so he could eventually assassinate him. Martorano’s defense of his choice to be dishonest in this one special case is admittedly logical, if chilling: “I couldn’t talk to him and tell him I was gonna shoot him,” he says, in a tone that suggests anyone would understand his plight.

Brennan moves on to establish that Martorano had free will when he killed all the people he’s admitted to killing and was not in fact a slave to the orders of Whitey Bulger. Martorano admits that it was he who pulled the trigger. But Whitey was the decision-maker. “He would tell me sometimes what to do,” says Martorano. “He knew the right buttons to press.”

“Were you kowtowing to him, Mr. Martorano?” asks Brennan. “Pahdon me?” asks Martorano, as a look of utter puzzlement flashes across his corpulent face. It seems a good bet that “kowtowing” is not within his vocabulary.

Handout photo by Reuters

There have been a few other notable vocab moments over the course of Martorano’s testimony. On Tuesday, he described how an FBI agent gone bad had given him a physical description of Tulsa, Okla., businessman Roger Wheeler. (Martorano needed it so he could hunt down Wheeler and kill him.) “It was his height, his weight. It said he had like a … a ‘ruddy’ face?” explained Martorano, haltingly.

Prosecutor Fred Wyshak sought to clarify: “Is there something unusual about that word? Ruddy?”

Martorano answered, “I never heard it before. It’s an FBI term, I guess?”

Today, Wyshak again searches for le bon mot. “Yesterday you used the word Judas to describe your feelings about committing these murders,” says Wyshak, inviting Martorano to elaborate.

“A Judas is a person that’s like an informant,” explains Martorano. “Just a rat, just a no-good guy. I was brought up to believe that’s the worst person in the world. As far as being a rat, that’s the opposite of how I want to live.” Which is an intriguing statement for someone to make as he sits on a witness stand, testifying against an old friend.

When he’s not attacking Martorano’s credibility, Brennan manages to elicit some intriguing details about the killer’s current post-prison lifestyle. It seems Martorano has been earning a reasonable wage—something on the order of $325,000 for the rights to his story, so far—a sum made possible because his plea agreement did not preclude him from profiting from publicity associated with his crimes. What’s he doing with this money (and the Social Security checks he also collects)? He’s been taking it straight to the casino.

Martorano explains that he bankrolls a gambler friend, taking a percentage of the guy’s winnings. Why doesn’t he just gamble himself? Because the other guy is better at it. Which might make sense if this were a game involving skill, like poker, or shrewdness, like horse handicapping. But Martorano’s game is dice. I’ve played a fair amount of craps in my day, and I can assure you it doesn’t require an advanced degree to figure out proper strategy.

Brennan forces Martorano to defend his appearance on 60 Minutes (it turns out the late Ed Bradley was an old acquaintance from Rhode Island who asked Martorano to come on the show) and his involvement in a book, titled Hitman, that he worked on with journalist Howie Carr. Martorano says not everything in that book is entirely accurate. “Writers have their prerogatives,” he tells the jury. “They put what they want in.”

Indeed, we do have our prerogatives. And I’m thinking it’s my prerogative to take a break from covering this trial. Particularly after Martorano is excused, and the next witness is a hamhock-faced Boston detective in charge of presenting a long series of decades-old crime scene photos from the police department’s cold-case archives. Evidentiary process is a far less interesting subject than cold-blooded murder.

So I’ll take my leave for the time being. I’ll likely be back here later on, as events warrant. Don’t worry—the trial is expected to last until September.

And Whitey will be there, every day, sitting bolt upright, ankles crossed, clothed in his blue jeans; long-sleeve shirt; and a fixed, withering stare. A few days ago, I asked a courtroom artist (her name is Jane Flavell Collins, and she draws mostly for a local Boston TV station) what it’s like to capture Whitey on her sketchpad. “Oh, he’s my favorite to draw,” she said. “It helps that he stays so still.”