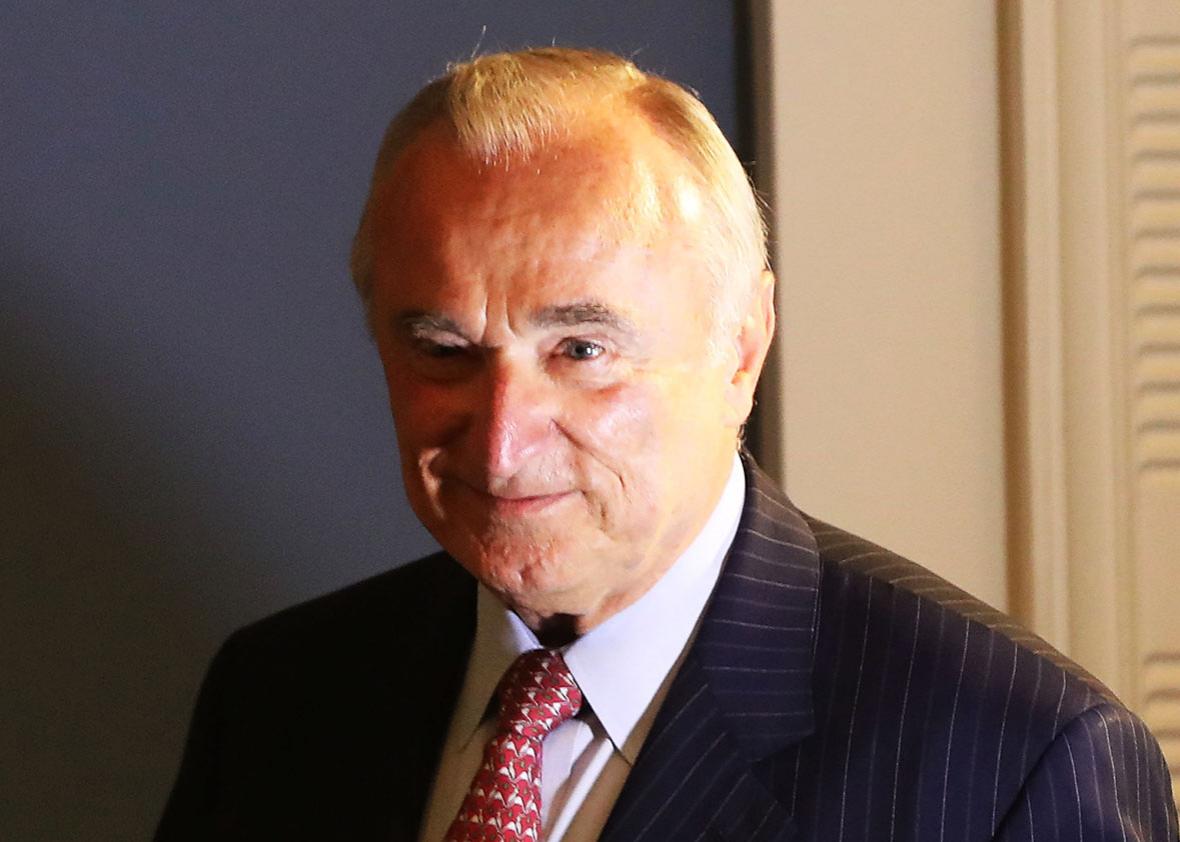

William Bratton, who announced on Tuesday that he will soon be retiring as commissioner of the NYPD, is most closely identified with his years policing that city. Bratton enjoyed two tours of duty in New York—starting with a career-defining stint under Mayor Rudy Giuliani, during which he established himself as a leader in American policing, and returning under Bill de Blasio in 2014. But Bratton’s longest stretch as the head of a police department was not in New York—it was in Los Angeles, where he served as chief of the LAPD from 2002 until 2009.

Bratton’s arrival in L.A. followed a decade of tumult that began with the 1992 Rodney King riots and continued with the Rampart scandal of the late ’90s. And while Bratton tends to get credit for helping the city out of that dark period—as the New York Times pointed out in its career retrospective Tuesday, violent crime fell by more than 50 percent on his watch, and the federal consent decree that had been imposed on the department in 2001 was lifted shortly before his departure—his time in L.A. has received less scrutiny than his time in New York.

For an assessment of Bratton’s tenure with the LAPD, I called longtime Los Angeles Times crime journalist Jill Leovy, who interviewed Bratton numerous times as part of her reporting on law enforcement and homicide. Leovy, who is also the author of Ghettoside, talked about the state of the police department Bratton inherited from his predecessor, the nakedly political approach he brought to the job, and why the seven years he spent with the LAPD are key to understanding his legacy. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Leon Neyfakh: Bratton became the chief of the LAPD in the fall of 2002. What was happening in Los Angeles at that time, and what did the city need from its head of law enforcement?

Jill Leovy: This is something that we on the West Coast are always a little sensitive about: The LAPD had been a very big story since the riots of ’92. And yet the internal workings of the LAPD remained a local story, and our real change-maker, Chief Bernard Parks, was not really a national figure, at least not in the same way that Bratton was. So all these major, major things were happening in L.A., but no one was paying attention until Bratton, who had this name recognition on the East Coast, came to town. Suddenly LAPD reform was big news. It created, I think, a distorted picture. The real story of Bratton, I would say, is that the big work and the traumatic change in the LAPD happened right before he came, under Bernard Parks. That was the watershed period. And in some ways Bratton basically came in to ride out the aftermath of all that.

You’re talking about the years between 1992 and 2002?

Right. A number of things happened during that time. After ’92, a slate of reforms was recommended, but there was a lot of dissatisfaction from police critics, who thought those reforms hadn’t really been enacted. Then, under Bernard Parks’ watch the department discovered the Rampart scandal, which was this hair-raising scandal involving corrupt police officers in a very tough division in downtown L.A. And Bernard Parks decided to use that corruption scandal to kind of push through reforms that had been lingering unfinished. He wrote this huge Board of Inquiry report. It didn’t just look at the Rampart scandal—it looked at a whole lot of management failings, in his view, within the LAPD, and suggested remedies. It was a very interesting report, but it was local news in L.A., and it wasn’t on the national agenda. And what happened is the Feds came in and sued, and the consent decree that was eventually agreed to by the LAPD ended up being almost word for word Bernard Parks’ report on what should be done.

As a reform agenda it was thunderous—it really shook the department to the bones. And the key thing is that Parks was able to enact a lot of reforms before he left. So in some ways Bratton just had to ride it out, and he got all the benefit of being a change-agent.

But the consent decree wasn’t lifted until 2009, right? So there was more work to do.

Yeah, because a lot of things were added on later. I actually knew an officer who was a night sergeant, whose huge headache in life was the TDD line for the deaf. [According to the consent decree] it had to be flipped on every night on the watch desk phone in case a deaf person called. And you know, it’s a busy station, and no one could ever remember to turn on the TDD line. It was just a nightmare for this sergeant because he was always being dinged for it, and he was like “What does this have to do with the Rampart scandal?”

So all of this stuff got added on to the consent decree. And so [while] they were not in compliance, it wasn’t necessarily because police officers were beating people up and shooting people left and right and no one could stop them. It was more like the TDD machine and stuff like that. So Bratton had to oversee all that, which was complex, but the ugly stuff had already happened.

So what was left for Bratton to do, besides making sure the TDD machine was on?

There were a lot of city politics. One of the things Bratton told me was that he made sure to get along with the mayors who appointed him. He was skillful about keeping his mayors happy. But he was a fascinating figure in the history of the LAPD because he was absolutely the opposite of Parks, and consciously so. Not in a bad way at all—but Parks, whom I knew quite well, really was not apologetic about being principled, even if the whole world didn’t understand, and he made what seemed like really dumb political moves. When Bratton came in, he said to me, more than once, I don’t apologize for being political—I actually think that is what I’m hired to do, to kind of broker the difficult politics around policing, and I consider myself extremely skilled at it. I think you cannot be above it. That’s what he said to me—that it was baloney to think you should be above politics. He believed politics was the job and he was supposed to be good at it.

What did he mean by the politics of the job?

So he would say, If I say one thing and it turns out it’s politically not doable, then I can change my mind tomorrow and do the opposite. And it’s not because I’m a hypocrite, it’s because responding and moving and being flexible politically is what I’m supposed to be. So some people would see him as completely cynical and inconsistent, but he always said, I don’t have to be about the principle, I’m supposed to be about the politics. I can change my mind. He told me once that he had a strategy of doing favors—if he hit some interest groups with something they didn’t like, he would do them a favor right afterwards just to keep them off-balance. He was always opposing one camp and then allying with them over something else.

He gave me a beautiful quote once: I said to him something to the effect of, “A lot of people think you’re very egotistical.” And he said, you know, I’m so egotistical that I can give it all away—I give other people credit for a lot of stuff I do, and I don’t care that I’m not getting credit; I’m happy to let people use it for their own political uses. It was like a chit—he handed those out in order to sort of keep this elaborate orchestra going. And he really put a lot of thought into it. It was fascinating to hear him talk about it. And what I thought was sort of touching about it is that he really in his heart didn’t feel himself to be a cynical politician. He said—and I think there’s something to this—The problem in policing is our political relations with civilian authority and with the people we police. And therefore the highest calling for a police leader is to be a skillful politician. That’s my job, to be skillfully manipulative.

I think a lot of people would be surprised by this characterization, because for one thing, he’s so closely associated with specific ideas about policing strategy—broken windows, especially.

I don’t mean to say he’s not principled—in some ways he is, and it’s true that the George Kelling stuff he has been loyal to his whole career. And he believes it—I think he considers himself a progressive, moderate police executive.

I’m not sure if people in New York see him as particularly talented politically. I’m sure there are lots of behind-the-scenes things he’s doing, but it doesn’t seem like he’s really been succeeding recently at selling the NYPD. There were protests outside City Hall before he announced his resignation where people were calling him racist and saying they wouldn’t leave until he stepped down.

Is he considered an incendiary figure in New York?

I wouldn’t say incendiary. But there was this moment recently, when there was a shooting at a hip-hop concert, and Bratton went on the radio and was like, These thugs who do this so-called rap music, these so-called artists, they attract these violent people to their shows and it’s a real problem. And it was kind of tone-deaf, politically—people were making fun of him as this out-of-touch old white guy who was using these racial code words from the ’90s.

You know what though? That stuff can play pretty well in the black underclass. You would be surprised. I wonder if he knew who he was talking to. Because when you go to, say the Nickerson Gardens housing project in L.A., you’re talking to people who are long-term poor, no wealth whatsoever, living on public assistance—they are really Derrick Bell’s Faces at the Bottom of the Well—and they are often socially conservative. This is one of the great paradoxes of the left. You go among that crowd and you’ll hear a lot about control your kids, we need to get back to the old values, et cetera. So maybe Bratton knew who he was talking to.

Remember, the view of the national activism community around policing and the views of people in Nickerson Gardens is very different. There’s a tendency to represent the one as the other. And there are actually great differences. In Los Angeles, Bratton was pretty good about getting out to that community meeting in a local gym when there’s been three shootings that none of the press is paying attention to and talking to people about it. A lot of the community leaders in black L.A. actually liked him a lot and had good relations with him and were impressed by that.

Tell me about your interactions with Bratton from when you were covering homicides in L.A.

I covered a lot of killings of young black men and Latino men that nobody else covered and nobody cared about. And Bratton would actually call me on my cellphone often on those stories, just to talk to me and say, I’m really glad you did that story. I’m glad someone took notice of this. He clearly had what a lot of cops have, which is a sense of pique and moral outrage that the misery and catastrophe that they see is not what their liberal critics seem to care about.

At the same time, I remember he once said—and it’s such an important point—he said something to the effect of, Policing is all about putting hands on people. You cannot take that out of the picture. He was sort of emphasizing that, ultimately, it is a job of physical incapacitation of people, and that there’s sort of an inchoate violence that is just part of the job. And he would kind of assert that in a way that the officers knew what he meant, and were sort of relieved that someone was finally saying it. And yet, he also didn’t offend the community. He did slip up sometimes and put his foot in his mouth, but he was pretty nimble about fixing it.

Did you feel like Bratton had a vision for what he wanted to do in L.A. when he started?

The one thing I would say about Bratton is that he didn’t consider himself a genius. He didn’t consider himself an innovator. He’s somebody who was always trying to tap these outsiders—John Linder and George Kelling and others—to bring him ideas that he would then implement. And the fact of the matter is the ideas he got, the innovative ideas we’ve had in policing over the last 20 to 30 years, haven’t been very good. So the fact that he implemented those ideas and they weren’t very good ideas—like this whole “targeted policing” thing, and “predictive policing,” and all that stuff about surgically responding and saturating neighborhoods after a crime has occurred. Well, that is just stop and frisk right? That is just stop and frisk with fancy names. But you get these highfalutin academics touting this stuff as innovative and progressive and new, and then you get someone like Bratton, who is just an ordinary cop, who sees it as his enlightened duty to bring it to fruition.

How does that relate to his conception of the police chief job as that of a politician?

I think part of his plan in L.A. was to heal some of the racial wounds and bring about what he always called a “peace dividend” and to heal relations through policing. As ironic as it seems, he actually, at that time, believed in policing as an instrument for healing race relations. So I think he wanted to do that. He saw politics as a way to integrate policing into society and to broker its place in a harmonized way.

I remember I wrote a long feature story back in the day when I was covering police, about the police officers at the public library and how they did their jobs. And it was a story I liked a lot, because they really wanted crazy people and homeless people to use the libraries, but people were always urinating on the carpet and stuff. So there were all these minor issues, and the story was about how the officers negotiated this fine line in policing. And I remember Bratton loved that story. He called me at home and wanted to talk about it. He talked about it, I think, to his staff, and said, you know, This is what policing is about. And it surprised me—it wasn’t even about the LAPD; it was about another police force. But it seemed to really touch what he cares about. And more power to him—to me, that was an interesting story about how police negotiate the discretion they have to enforce the law in order to help everyone get along. And to get people to not pee on the carpet.