It’s an article of faith among Democrats that, when speaking out about the need for police reform and gun control, it is imperative to step lightly. Lean too hard into the idea that trigger-happy police officers should be prosecuted and driven out of the profession, you risk being called a cop-hater willing to besmirch the badge to score political points. Neglect to mention your profound respect for the Second Amendment when you call for universal background checks, you can count on incurring the wrath of proudly law-abiding gun lovers everywhere—especially in swing states.

These are notoriously tough issues to navigate politically, and the consequence is that, too often, politicians deliver either mealy-mouthed banality or silence. What the Clinton campaign did during the second night of the Democratic National Convention was different. Over the course of a roughly 30-minute-long suite of remarks broadly devoted to the need for criminal justice reform, one speaker after another demonstrated just how expertly the Clinton operation has honed its messaging on both guns and police brutality—and they did so without sacrificing potency or conviction.

The jiujitsu started with a tried-and-true set of “to be sure” maneuvers from President Obama’s former attorney general, Eric Holder. Holder, who has tended to be unapologetically liberal on the subject of criminal justice reform, took pains to emphasize that even people convinced there is something rotten in American law enforcement must hold police officers in the highest esteem and take seriously their contribution to society. “It is not enough for us to praise law enforcement officers after they are killed,” Holder said, adding that “we [must] come to realize that keeping our officers safe is not inconsistent with ensuring that those in law enforcement treat the people they are sworn to serve with dignity, with respect, and with fairness.” The reasonable position, he suggested, is to commit to both goals.

The levelheadedness continued with Pittsburgh Police Chief Cameron McLay, who unequivocally asserted the existence of a “crisis of trust” between police and citizens while testifying to the sense of siege that many in the law enforcement community are feeling after the shootings in Dallas and Baton Rouge, Louisiana. McLay then made two uncontroversial but nevertheless important points: that the 25-year crime decline has occurred against a backdrop of declining faith in the legitimacy of law enforcement in some communities, and that police officers are increasingly being forced to deal with the violence and chaos borne of “declining economic opportunities, divestment in mental health, and the absence of effective drug treatment options for those addicted.”

McLay’s evenhanded rhetoric stood in stark contrast to the words of the president of the Fraternal Order of Police’s chapter in Philadelphia, who on July 20 issued an open letter decrying the Clinton campaign. The union leader expressed shock that the DNC had tapped the mothers of police violence victims to speak at the convention, but had not invited relatives of police officers killed in the line of duty. “It is sad that that to win an election Mrs. Clinton must pander to the interests of people who do not know all the facts,” the letter read, “while the men and women they seek to destroy are outside protecting the political institutions of this country.”

There are structural and economic reasons why police union leaders often employ such an ominous tone when they make public statements on behalf of their members. But it’s unfortunate that many Americans are thus led to believe that these extreme statements are representative of how most police officers feel. If reasoned voices like McLay’s were louder—if the conciliatory, realistic description of the world he presented on Tuesday night was easier to hear over the umbrage of union leaders—the debate over police reform might be less polarized and divisive. The Clinton campaign deserves credit for giving a platform to a law enforcement official who sees the complexity of the issues at hand and resists the temptation to choose sides.

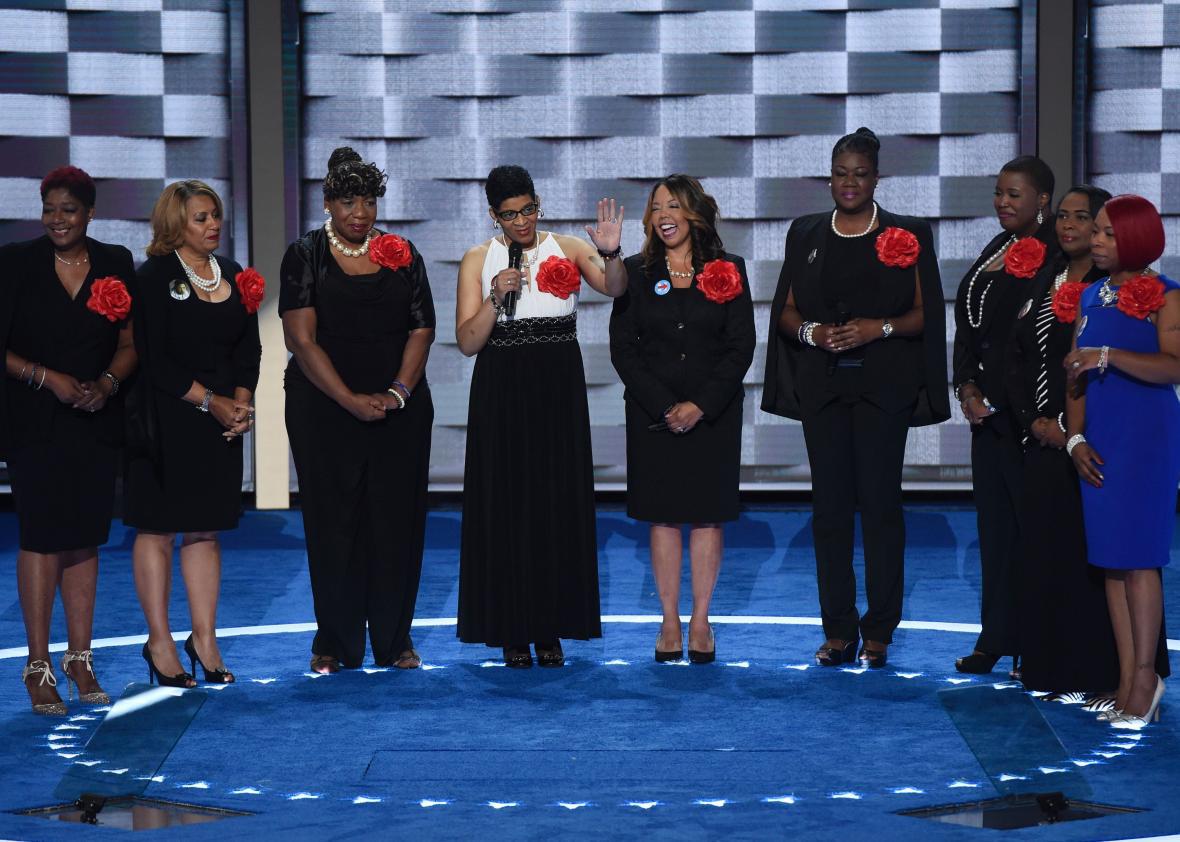

With the exception of Bill Clinton’s speech, the main event on Tuesday night was the appearance onstage of seven women who have lost children to police and gun violence. It was during this portion of the proceedings that the political strategy informing Clinton’s platform on criminal justice seemed most apparent. Ostensibly, giving such a high-profile speaking slot to the so-called “Mothers of the Movement” was a clear signal to the party faithful that the Democratic establishment is concerned about police and gun violence, and it drew a contrast with the law-and-order-heavy proceedings at the RNC in Cleveland.

Yet of the three women who spoke—the mothers of Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin, and Jordan Davis—none told stories of murderous police officers: In Bland’s case, the cause of death was suicide; Martin was the victim of a vigilante; Davis of a civilian at a gas station. While there were women onstage whose children had been killed by police, they remained in the background while Geneva Reed-Veal, Lucia McBath, and Sybrina Fulton delivered their poignant and heart-rending remarks. As a result, Clinton’s support for the Black Lives Matter movement was plainly communicated but no police officers were explicitly criticized—and no one incident was saddled with the burden of being a “perfect” parable for the issue at hand.

Perhaps the savviest aspect of the Mothers segment was that the Clinton campaign combined—and blurred together—the issues of police violence and gun control: the mother of Hadiya Pendleton, who died of a gunshot wound in Chicago because she was mistaken for a gang member, shared the stage with the mother of Eric Garner, who died after a police officer put him in a chokehold. The effect was to highlight the fact that too many black Americans are dying violent, premature deaths, while suggesting the search for solutions not in terms of gun control or police reform but something broader. The move surely failed to appease the most vociferous gun rights enthusiasts or intransigent opponents of Black Lives Matter, but it’s possible that for a certain subset of voters, it took the edge off two issues that have sharply divided Americans.

In the moments immediately following the Mothers of the Movement speech, a group of talking heads on CNN, including former Obama adviser David Axelrod, discussed whether the program would have been more effective had it included the widows of fallen police officers. The implication was that the Clinton campaign hadn’t done enough to signal its reverence for law enforcement, that the DNC had committed an easily avoidable error by alienating police when they could have brought them into the fold.