On Sunday, CNN’s Jake Tapper asked Donald Trump if he would disavow the Ku Klux Klan’s former “grand wizard” David Duke, who had advised his followers that voting against Trump would be an act of “treason” against their heritage as white people. Trump repeatedly declined to distance himself from Duke or the KKK, saying he didn’t know enough about the man or the specific group in question to make a statement one way or another.

It was a chilling moment. Here was the Republican front-runner for president seeming to signal his tolerance, if not his actual support, for the Ku Klux Klan, an organization synonymous in American culture with murderous racism. The group’s name alone brings to mind an evil conspiracy, and its iconography—the hoods, burning crosses, and strange honorifics—evokes an organized army of violent zealots.

But what is the Ku Klux Klan in 2016? What do its members actually do when they get together, and what power do they wield? Many of our associations, it would seem, come from the group’s long history more than its present. According to Mark Potok, a senior fellow at the Southern Poverty Law Center and an expert on extremist hate groups, there have been four distinct periods of Klan activity, starting with its emergence in the South during Reconstruction as a network of secret militias that lynched and otherwise terrorized black people. The second wave crested in the 1920s, when the KKK became almost unimaginably large and influential, with an estimated 4 million members and real political influence. The third wave of the KKK rose in response to the civil rights movement, serving as a kind of enforcement squad for Jim Crow: During this period, KKK groups enjoyed the loyalty of some Southern police departments as they carried out bombings against black churches and homes, and murdered multiple civil rights activists. The Klan’s fourth wave was born in the late 1970s and distinguished itself primarily through David Duke’s attempt to professionalize the organization, trading robes in for suits and actively pursuing legitimate political power to advance a white supremacist agenda.

Where does that leave the KKK today? Does it remain a highly organized paramilitary organization with ties to law enforcement and real if clandestine political clout? There’s no doubt that Trump should have disavowed the group, and failing to do so signaled an unforgiveable political calculation. But what exactly would he have been disavowing?

To find out, I interviewed several experts who study white supremacist organizations, as well as a photojournalist who has embedded with KKK members multiple times over the past 10 years. I also spent time on several KKK websites and spoke to a Klansman based in Texas who identified himself as a “grand kleagle.”

What I learned is that “the KKK” no longer really exists, at least not as the monolithic group of vigilantes it once was. Today, it’s a collection of 30 or so independent groups made up of small local chapters that embrace the KKK “brand” and some of its traditions as a means of appearing more formidable than they are. The groups have imposing names like the “International Keystone Knights of the Ku Klux Klan” and “Imperial Klans of America Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.” But while the KKK once stood as a hierarchical organization with terrifying goals and the means to achieve them, its descendants can best be described as a very loosely affiliated network of small groups that are all but irrelevant as political entities and marginal even within the white supremacist movement.

According to University of Pittsburgh’s Kathleen Blee, a sociologist who studies hate groups, these cliques usually don’t even get along with one other: “From the outside it seems like it’s one movement, but on the inside it’s very fractious,” she said. “There’s a tremendous distrust between the groups, and the leaders are often very antagonistic toward each other.” For example, the Loyal White Knights of the KKK and the Traditionalist American Knights of the KKK are locked in a feud stemming from a rumor that the “imperial wizard” who runs the latter group is secretly Jewish.

Some individuals who self-identify as members of KKK groups are undoubtedly dangerous. Fresh evidence of this appeared just last week, when a rally staged by the LWK in Anaheim, California, provoked a melee that resulted in three counterprotesters being stabbed. And while the KKK members on the scene claimed self-defense, it’s safe to say the violence was not engaged in reluctantly: On the voicemail message that plays when you call the LWK’s toll-free hotline, you can hear a gruff voice brag that KKK members “fought back” and put one of the counterprotesters “in the hospital in critical condition.”

Other groups continue to try to flex some political muscle. According to Anthony Karen, the photojournalist I spoke to, there are certain groups that “hold frequent public demonstrations in opposition of such things as illegal immigration, same-sex marriage, and advocating bringing prayer back to public school.” But far from all Klan members have a set “goal” in mind, he said in an email. As Karen’s extraordinary photos of the Klan suggest, “Some join for nothing more than wanting to be in the company of ‘like-minded white people.’ ”

Take as an example the Ku Klos Knights, a group that, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, has local chapters (known internally as “klaverns”) in 13 states. When you visit the group’s official website—yes, they have one, as do many of today’s KKK-adjacent organizations—you find low-resolution animated GIFs of the Confederate flag, a link to a one-page membership application that costs $10 to submit, and a “humor” section full of racist memes. Most prominent, however, are links to the official Ku Klos Knights online store, where you can purchase “everything a Klansman or Klavern needs,” including patches, T-shirts, and Klan literature, including “The Art and Practice of Klannishness.”

The Ku Klos Knights’ site also includes a telling proclamation:

This is to inform any and all current and future members of the Ku Klos Knights that we are a secretive Klan and we believe in total secrecy for ourselves and our members. No one shall ever admit at any time that they are a member of our klan and shall at no time admit to who IS a member of our klan. … We do not wear our uniforms or robes in public, nor do we assemble for public demonstrations.

While its members are united by a shared faith in white supremacy and the joys of cross-burning—the practice has its origins in medieval Europe, but became part of Klan pageantry after it was featured in The Birth of a Nation—the fact that there’s a policy against public assembly and demonstration suggests, again, that this is more of a social club for racists than an active political or terrorist group.

It is of course possible that groups like the Ku Klos Knights present a public face that belies a more nefarious purpose. But the experts I talked to said that modern Klan groups do, in fact, mostly keep to themselves. “What they don’t have so much anymore is the strategic planning side that they used to have,” said Blee. “It’s just cultural now. Some of them are still trying to plan things, but as a whole they don’t have the size or the organizational strength to sustain that part of it anymore.”

“We’re talking about insular types of activities—so, private gatherings that they’re using to build solidarity with each other, and to build a collective identity,” said University of Nebraska–Omaha sociologist Pete Simi, who attended cross-burnings and other white supremacist gatherings as field work for the book he co-authored, American Swastika. “They call it fellowshipping,” he said. “You’re there to fellowship with your comrades.”

The website of the Southern Mountain Knights, which has multiple klaverns in Tennessee and, like the Ku Klos Knights, has a policy of never holding public rallies, offers a window onto how contemporary Klan gatherings look and feel. On June 17, 2013, for instance, word went out about the group’s annual barbecue:

The event like always is free. This is our third annual BBQ and each one seems to be better and better. While the event is free, we ask any member attending to please bring a dish or a drink. Like always, no beer or alcohol allowed. Weapons are allowed, but will be locked up by our Knight Hawks until the event is over. We don’t want accidents to happen.

More recently, in March 2014, the Knights announced their third annual leadership summit:

We expect all Klavern leaders to attend. The event is being held June 6-8. The event includes voting, food, vendors, music, speeches and of course, a cross lighting Sunday night. If you are going to be part of the Cross lighting, make sure you have your robe. If you are in need of a robe, please contact me at granddragon@inbox.com.

Potok, of the SPLC, told me these listings are fairly representative of what most Klan “meetings” look like these days. “Quite a lot of the Klan groups are in effect extended families,” he said. He estimates that there are currently between 4,000 and 6,000 self-identified Klansmen across the country. “By and large these are just people who live close to each other and see each other a lot.” Still, Potok emphasized that there have been recent instances of serious Klan-related violence: Before the Anaheim incident, there was the case of three prison guards believed to be members of a Klan group who were arrested on suspicion of plotting a murder against a black inmate, and before that there was a shooting spree perpetrated outside a Jewish Community Center in Kansas by former Klansman Frazier Glenn Cross.

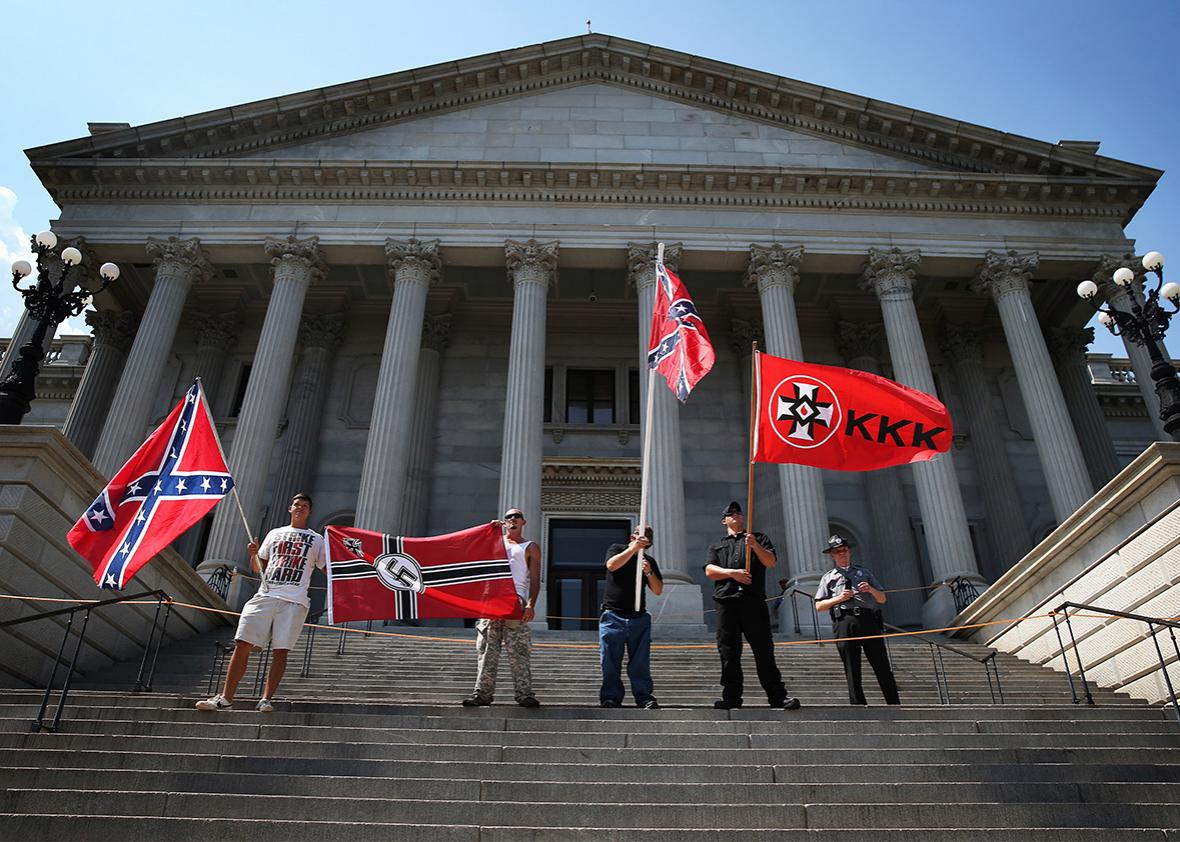

And even small and disorganized Klan cells have the potential to provide spiritual support to the broader white supremacist movement, which unlike the KKK seems to have enjoyed a resurgence during the Obama years. That movement remains a major threat, as evidenced in devastating fashion last summer when white supremacist Dylann Roof allegedly murdered nine black people at a Charleston church. Roof was not, as far as anyone knows, a member of any formal Klan organization, but the national debate over the Confederate flag that followed the Charleston massacre seemed to energize some Klan members, aligning them with other white supremacist organizations, and inspiring them to rally publicly in defense of their so-called heritage.

“The KKK groups are now embedded in a larger world of neo-Nazi white nationalist type groups,” said Simi. “On their own, their significance, you could argue, is minimal. But you really have to understand them within that larger subculture. That’s where their significance lies.”

Still, according to Potok, the texture of actual Klan life in 2016 skews mostly toward spending quality time with fellow racists. “An awful lot of it is going to your imperial wizard’s house and having a barbecue, sitting around, talking ugly about certain groups of people,” Potok said. “They really do look like rural cookouts.”

My phone call with the grand kleagle from Texas, who declined to tell me his name because some of his friends don’t know he’s a Klansman, tracked with Potok’s characterization. The organization this 63-year-old man belongs to is called the United White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, and I reached him by calling the number posted on the website of its Texas chapter. In a deliberate cadence, the man explained that the group of roughly 15 people he’s been part of for the past four years was “based on Christ and the ways of the Bible,” and that they are a “tightknit clan, like a family.”

“Our thoughts are to maintain the white race and give a future for our white children,” he said. “So we’re just trying to have our own voice, you know.”

They don’t use that voice publicly, he said. Instead, they gather at each other’s houses and look for deserted spots in the woods where they can burn crosses and pray while wearing their regalia. “Part of the fun is trying to find a place that’s out of the way and won’t be seen and won’t be intruded upon.”

The group holds meetings a few times a month, the man told me, and uses them to discuss Klan business. “Different things come up,” he said. “There could be a myriad of things we’re trying to iron out, either with the website, or maintaining the post office box.” At the next meeting, he said, the expectation is that one of his Klan brothers will introduce his new baby to the group. Afterward, they’ll probably get to “smoking a brisket or two … drinking beer, maybe sampling the food as it comes off the grill.”

I asked him if there was any interaction between his chapter of the United White Knights and the ones that exist in other states.

“Oh yeah,” he said. “Some of our ceremonial rallies, we invite maybe the Arkansas realms, or the Louisiana realms. Mississippi, Alabama. All of them will come.” Still, he said, “There’s members I’ve never met yet. But I’m sure I’d like them as well.”

I asked him what he thought of Donald Trump.

“He’s a pretty wild dude who would do some major changes in the world if he was the president,” he said. “In a good way—a unique way, but a better way.”