After months of hype about the historic bipartisan consensus that we must make the American criminal justice system less harsh, President Obama finally signed a justice reform bill into law Monday. There’s only one problem: Instead of making the justice system more fair and less punitive, the new law will make it more vindictive and petty. Specifically, it will require people who have been convicted of sex crimes against minors to carry special passports in which their status as registered sex offenders will be marked with conspicuous identifying marks.

The point of International Megan’s Law, in the words of its House sponsor Chris Smith of New Jersey, is to prevent “sex tourism” by making it harder for people to “hop on planes and go to places for a week or two and abuse little children.” In addition to the passport stamp, this goal is supposed to be achieved through the formation of a new federal unit inside of Immigration and Customs Enforcement called the “Angel Watch Center,” which will inform foreign governments when American sex offenders have made plans to visit their countries.

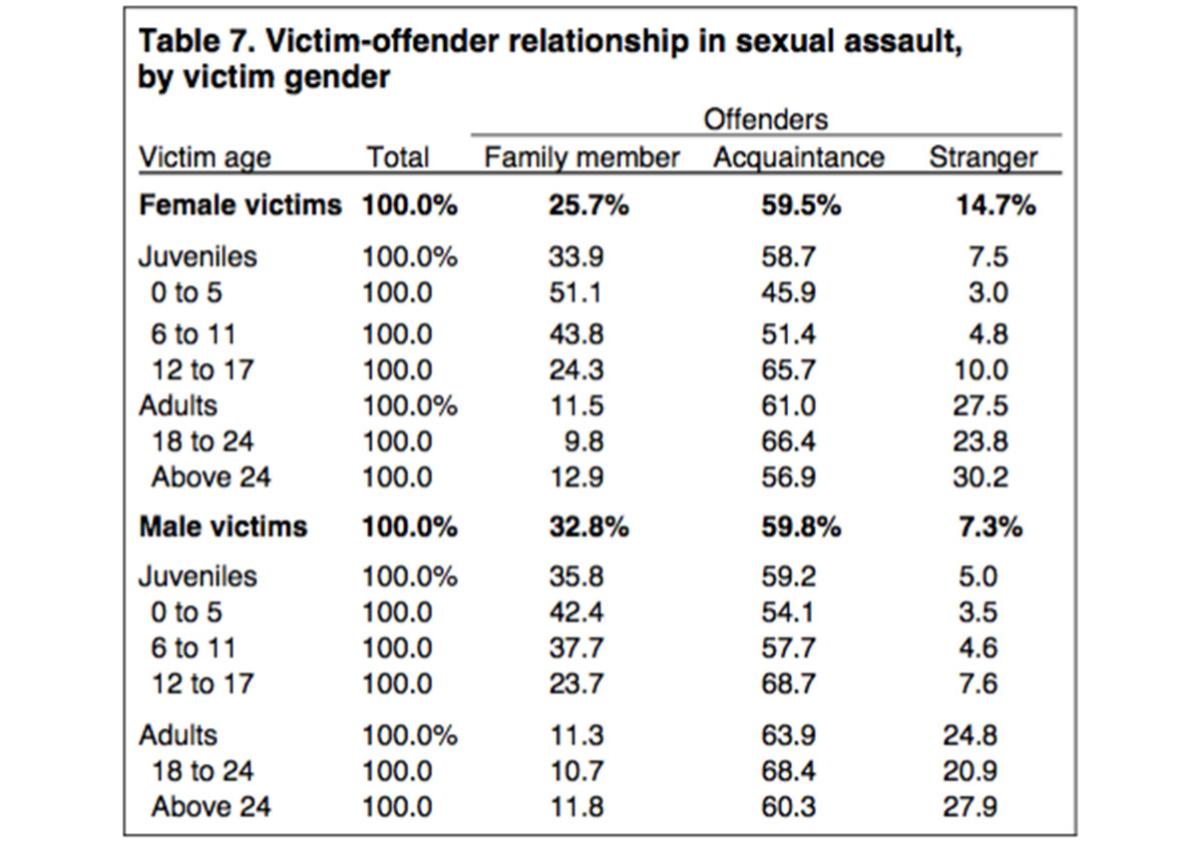

You might be thinking that sounds like a good idea—a wise precaution that promises to prevent confirmed perverts from victimizing more people. But like the domestic sex offender registry it’s based on, the law is premised on a profound and consequential misunderstanding of how sex crimes against minors are usually perpetrated. Though it’s understandable that parents are concerned about “stranger danger,” the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics indicates that the vast majority of sex abuse victims are attacked not by strangers hunting for prey, but by family members and other acquaintances.

Bureau of Justice Statistics

The other myth the new law perpetuates is that people who commit sex crimes are much more likely than other types of criminals to recidivate and find new victims after they’ve been released. A BJS report shows that insofar as that’s true, we’re still talking about a tiny percentage of people: According to the findings, just 5.3 percent of the 9,691 released sex offenders in the study sample were rearrested for a sex crime within three years of their release. Among male child molesters specifically, recidivism appears to be even lower: of the 4,295 male child molesters in the sample, just 3.3 percent were rearrested for another sex crime against a child within three years of their release.

It’s difficult to understand, in light of these findings, how making it harder for sex offenders to travel internationally is going to help reduce the frequency of child sex abuse. What will the new law achieve instead? Further marginalization of a group of people that Democrats and Republicans alike apparently consider to be deserving of permanent social exile and never-ending suspicion.

To state the obvious, it’s hard for many people to summon much sympathy for sex offenders, and that is perfectly understandable. However, it’s crucial to remember that the category includes all sorts of people, including those who were placed on the registry when they themselves were children. Here’s how Rep. Bobby Scott put it in a statement on the House floor in which he expressed his opposition to the idea of marking sex offenders’ passports with a special indicator:

The failure of this provision to allow for the individualized consideration of the facts and circumstances surrounding the traveler’s criminal history, including how much time has elapsed since his last offense, underscores how this provision is overbroad. Details such as whether the traveler is a serial child rapist versus someone with a decades-old conviction from when he was 19-years-old and his girlfriend was 14 … are significant, and would allow law enforcement to more appropriately prioritize their finite resources.

Scott also argued that “it is simply bad policy to single out one category of offenses for this type of treatment,” noting that “we do not subject those who murder, who defraud the government or our fellow citizens of millions and billions, or who commit acts of terrorism to these restrictions.”

Some might ask, Well, why don’t we? The answer is that there’s a deeply questionable moral calculus involved in holding people’s crimes against them long after they’ve paid their debt to society. In theory if not in practice, our justice system is built on the idea that this is wrong. Yet when it comes to sex offenders, American lawmakers seem not just willing but eager to impose punishment forever—a tendency that has resulted in sex offenders all over the country being forced into homelessness because residency restrictions have made it impossible for them to find housing. In its most extreme form, the idea that sex offenders never stop being dangerous has resulted in thousands of people being held indefinitely in “civil commitment” long after they’ve completed their prison terms.

Compared to that terrible practice, the law Obama just signed is small potatoes, and its life-ruining potential is low. But its quick and friction-free passage is significant nonetheless: at a time when it seemed possible that U.S. lawmakers were finally starting to believe that even people convicted of crimes can be trusted to change, it shows just how little willingness there is, on either side of the aisle, to push back on our intuitive fears and revulsions.

On the one hand, it’s understandable that Obama couldn’t bring himself to veto a bill that purports to protect children from sexual predators. On the other, he should have been able to see that this law is unlikely to achieve anything besides making some Americans feel even more ostracized than they already do. That’s not criminal justice reform. It’s just politics.