Among those invited to this year’s State of the Union address was an ex-convict who spent six years and nine months in an Arizona women’s prison. Her presence was no doubt intended to underscore President Obama’s position on criminal justice reform, a cause he has prioritized over the past six months amid bipartisan calls to reduce the American prison population and take a less punitive approach to drug offenders.

Insofar as the ex-con at the State of the Union was intended to be the face of the mass incarceration problem, she was an odd choice. Imprisoned for committing securities fraud, Sue Ellen Allen is a wealthy white woman whose past life had her designing jewelry for the likes of Margaret Thatcher and Barbara Bush and publishing poetry in Cosmopolitan. By contrast, the majority of the 1.35 million people in America’s state prisons are poor, and a disproportionate number of them are black or Hispanic. Whereas Allen is a so-called white-collar criminal, 53.2 percent of state prisoners were convicted of violent crimes, and 15.7 percent were convicted of drug crimes.

Allen surely got her invite to Tuesday’s speech not because of who she was when she went to prison but what she became after she left: an enthusiastic advocate for reform, with a particular focus on helping people behind bars receive job training and education. “If you had told me what I was going to see and experience in prison, I would have said, ‘Not in my country. We don’t treat people that way,’ ” Allen told BuzzFeed recently. “I was wrong.”

Allen is the first to admit she was not an average inmate—“I was well-educated, I was privileged because I have white skin”—and she is explicit about using her position to help people she would have never crossed paths with in her preconviction life. In this respect, Allen is part of an American tradition—of powerful individuals being humbled by the law after being convicted of criminal misconduct, then converting to the cause of criminal justice reform in response to the cruelty and unfairness they experienced firsthand.

From Pat Nolan, the former California lawmaker turned conservative prison activist, to Orange Is the New Black author Piper Kerman, some of these people have unquestionably done valuable work on behalf of prison reform—work that many other similarly situated convicts have declined to undertake. And yet there is something darkly comic about the influence they wield in the reform movement and the moral force with which some of them speak on issues they might not have thought much about before they found themselves behind bars. A cynic might see in their embrace of reform proof of mankind’s solipsism—a reminder that most of us can’t appreciate a problem like mass incarceration until we experience it ourselves. A pragmatist might look past this and welcome the involvement of committed, and deep-pocketed, advocates in the fight against a problem that primarily affects the powerless.

Below, a guide to some of the upper-crusters whose interactions with the justice system convinced them that change can’t wait.

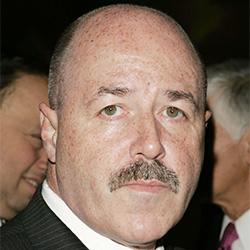

Bernard Kerik

Photo by Peter Kramer/Getty Images

Before the fall: Started his career in law enforcement as a bodyguard to Rudy Giuliani. Became head of New York City’s Department of Corrections in 1998, then served as NYPD commissioner. Was set to become secretary of the Department of Homeland Security under George W. Bush when his career was engulfed in scandal.

Conviction: Pleaded guilty to federal charges of tax fraud and making false statements stemming from renovation work on his Bronx home that was paid for by a shady construction firm in New Jersey. The firm was apparently hoping to use Kerik’s influence to secure business in New York.

Punishment: Served three years in a minimum-security prison in Maryland and spent five months under home confinement in his family’s New Jersey mansion. Finished serving his sentence in the fall of 2013. On probation till October.

Revelation: From a “white paper” he sent to then–Attorney General Eric Holder from prison: “I have learned that just because these men are here in prison, they are not all ‘bad’ men. … Most would give anything to turn back time to make it right.”

Told the New Yorker last spring, “You never pay your debt to society. If you’re a convicted felon, you’re punished until the day you die. It’s not right, and the land of second chances is a farce. There are no second chances, unless you’re somebody like Martha Stewart.”

Contribution to the cause: Wrote a book called From Jailer to Jailed: My Journey from Correction and Police Commissioner to Inmate #84888-054, in which he described “the torture of solitary confinement, the abuse of power, the mental and physical torment of being locked up in a cage” and argued for a less punitive justice system.

Founded a nonprofit called the American Coalition for Criminal Justice Reform that advocates for reducing the prison population, getting rid of some mandatory minimums, and restoring rights to felons postrelease.

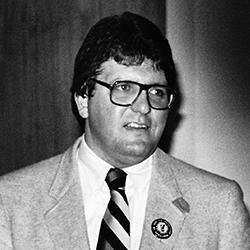

Pat Nolan

Before the fall: Top Republican lawmaker in the California State Assembly, considered a possible candidate for governor.

Image by ChrisHumphrey/Wikimedia Commons

Conviction: Accepted $10,000 in what he thought were political donations from what he thought was a shrimp-processing company looking for help securing a state loan. It turned out the company was the face of an FBI sting operation hunting corrupt politicians.

Punishment: Nolan pleaded guilty to one count of racketeering and spent 25 months in federal prison.

Revelation: “I had assumed they did all they could to help prepare the guys to return to society and make a better life,” Nolan told Marshall Project editor Bill Keller in a recent New Yorker story. “But they were just warehousing them. … The implication is: you’re worthless, you come from nothing, you are nothing, you’ll never be anything.”

Contribution to the cause: As the head of the Justice Fellowship, an organization founded by one-time Nixon lawyer Chuck Colson—who would be on this list himself if he were still alive—Nolan was a key advocate of the 2003 Prison Rape Elimination Act and has since come to play a crucial role in building conservative support for criminal justice reform in Congress.

Kevin Ring

Screenshot via Reason TV

Before the fall: Lobbyist under Jack Abramoff. Before that, as a Capitol Hill aide, helped his then-boss John Ashcroft write harsh mandatory minimum laws for methamphetamine offenses.

Conviction: Worked for Abramoff, who was famously convicted in a massive bribery and fraud scandal. In 2011, Ring was found guilty by a jury on charges stemming from meals and tickets he provided to public officials.

Punishment: Spent 15 months of a 20-month sentence at a minimum-security prison “camp” attached to the Federal Correctional Institution–Cumberland facility in Maryland, then served the rest under home confinement.

Revelation: “Mandatory minimum sentencing laws can no longer be defended,” Ring wrote in a recent op-ed. “With modest improvements, we can ensure that violent and dangerous repeat criminals continue to get the stiff sentences they deserve while nonviolent offenders get shorter, more proportionate sentences.”

Asked about his support for the meth laws, Ring told Roll Call, “The Hill is run by too many 20-year-olds with a lot of opinions and not enough experience, and I was part of that. I didn’t have enough experience to write criminal statutes. What did I know?”

Contribution to the cause: Since his release from prison in 2015, Ring has served as the director of strategic initiatives for Families Against Mandatory Minimums, working behind the scenes in support of sentencing reform in Congress.

Frank Quattrone

Before the fall: Tech investor. Head of Credit Suisse First Boston’s tech banking business. Helped take Amazon and Netscape public.

Photo by Stephen Chernin/Getty Images

Conviction: Found guilty in 2004 of obstructing justice and witness tampering in connection with efforts to “hinder a government investigation into whether [Credit Suisse] doled out shares of hot IPOs to favored clients in exchange for inflated commissions.”

Punishment: Sentenced to 18 months in prison but ultimately avoided incarceration after a judge threw out his conviction in 2006. The following year all charges against Quattrone were dropped.

Revelation: According to one account, “The day of Frank Quattrone’s conviction, [he and his wife] read a story in a local newspaper in California about a man who had been exonerated after 20 years in prison. The story showed that [Quattrone’s prosecution] was far from an isolated case, and it struck a chord with the Quattrones, who were compelled to conduct their own research, which educated them about the magnitude of the problem.”

Contribution to the cause: Donated $15 million to fund the University of Pennsylvania’s Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice, a “data-driven, interdisciplinary center geared to a sweeping reform of the criminal justice system through the systemic prevention of unjust outcomes.”

Piper Kerman

Before the fall: A graduate of Smith College from a well-to-do Boston family.

Photo by Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images

Conviction: Became romantically involved with a heroin dealer and was convicted of laundering money and drug trafficking.

Punishment: Served 13 months in a minimum-security women’s prison in Connecticut.

Revelation: From her memoir: “Prison is quite literally a ghetto in the most classic sense of the world, a place where the U.S. government now puts not only the dangerous but also the inconvenient—people who are mentally ill, people who are addicts, people who are poor and uneducated and unskilled.”

Contribution to the cause: Wrote the best-selling memoir, Orange Is the New Black: My Year in a Women’s Prison, which became a hit TV show on Netflix. Has since become a regular speaker at reform conferences and has testified before Congress about the specific challenges that women face in prison.

Don Siegelman

Photo by Henny Ray Abrams/Getty Images

Before the fall: Served as governor of Alabama from 1999 until 2003.

Conviction: Appointed a health care executive to an Alabama regulatory board, seemingly in exchange for a $500,000 political contribution. Convicted on charges of bribery, conspiracy, fraud, and obstruction of justice.

Punishment: Sentenced to 6½ years in prison, which he is still serving. Siegelman maintains his innocence. His projected release date is August 2017.

Revelation: “If this can happen to me, it can happen to anybody in this country.”

Contribution to the cause: So far mostly talk: an impassioned primer on criminal justice reform that calls for “killing the ‘Frankenstein Mass Incarceration Monster,’ ” and which his supporters sought to deliver to members of Congress; a statement in support of the SAFE Justice Act, a comprehensive criminal justice reform bill. Was placed in solitary confinement for eight weeks as a result of calling into a radio show last October to assert his innocence and advocate for reform.

Sue Ellen Allen

Courtesy of Gina’s Team

Before the fall: Worked as a jewelry designer. Her creations were carried in stores such as Saks Fifth Avenue and featured in Women’s Wear Daily. From the Phoenix New Times: “One of her signature pieces was a large, studded leopard she called Glamourpuss.”

Conviction: Facing an indictment for defrauding investors out of $1.1 million, Allen and her husband fled the country and spent years living under false names in Portugal. In 2002, sick with cancer, Allen turned herself in. (“With only two more chemo sessions to go, our cozy world, our three dogs and four cats, vegetable garden, fresh food and pillow-filled world collapsed,” she wrote in her memoir of prison life, The Slumber Party From Hell.)

Punishment: Spent just under seven years in the Perryville women’s prison in Arizona.

Revelation: “Most of the women who served time had to endure daily doses of humiliation,” Allen told Vice. “Repeatedly, staff members would tell the women that no one cared. Prison officials don’t want others to know what goes on in there, but prison life degrades people in ways that influence them forever.”

Contribution to the cause: After gaining her freedom in 2009, Allen founded the nonprofit Gina’s Team, named after a roommate she lived with in prison who died at 25 of leukemia. In Allen’s words, the organization brings “volunteer community leaders, speakers and educators into prisons to teach life skills subjects” and provides “inmates with much-needed tools for re-entry.”