This is the fifth installment in a series on victims of crime. Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

On the evening of March 18, 2007, Laura Sanchez, a 34-year-old mother of four, parked her van in front of her South Los Angeles home after a dance practice for her daughter’s upcoming quinceañera. Two carloads of black gang members cruising the neighborhood in search of Latino rivals spotted Sanchez’s 17-year-old honors student son opening the passenger door and decided, without knowing him, that he would do as their target. They started shooting. He ducked. The gunmen then took aim at the vehicle. One bullet pierced Sanchez’s heart. She died at the scene after her son and husband tried to save her with CPR.

Sanchez’s death came nine years after her own mother had died in a drive-by shooting while waiting on the front porch for Sanchez and her family to arrive for Thanksgiving dinner. Depressed and anxious after that loss, Sanchez feared for her children’s safety while doing her best to raise them in one of America’s most violent neighborhoods. A few days after Sanchez’s murder, her sister-in-law, Adela Barajas, helped neighborhood children organize a memorial peace march. “The kids wanted to do that every week until something changed,” Barajas remembers.

Laura Sanchez with her son Brian as a baby, on June 12, 2005. Photo provided by the family.

The marches continue today as a larger, annual event. In the intervening years, Barajas, a single mother of three, stepped in to help raise Sanchez’s children. (The children’s father, Barajas’ brother, suffered a nonfatal gunshot wound in a drive-by one year after their mother was killed.) Barajas spent months dogging city bureaucracy to get Sanchez’s family grief and trauma counseling, but the services fell far short of what they needed. The son who witnessed his mother’s killing faltered on his path toward academic success. His Aunt Adela is now raising his 3-year-old girl.

Now 49, Barajas works a warehouse office job from 5 a.m. to early afternoon. “That’s my easy job,” she says. She then spends her afternoons and evenings as the volunteer leader of a community group that counsels grieving family members, teaches them how to navigate the victim services system, and gives teens a safe place to go after school.

She pressured the city of Los Angeles to turn a neighborhood park—formerly a gang battleground—into a clean and well-equipped playground, community center, and gym. She also serves as her neighborhood’s liaison with the Los Angeles Police Department and, this summer, helped form a team of residents who have lost loved ones to murder. The idea is that members will race to homicide scenes to help counsel families newly inducted into their awful fraternity. She calls her organization Life After Uncivil Ruthless Acts—LAURA.

Photo by Mark Obbie

Americans are conditioned to see the harsh punishment of offenders as the best form of justice for crime victims. Barajas sees things differently. She and her allies focus on victims and offenders alike, emphasizing trauma care, crime prevention, and rehabilitation of former prisoners instead of police crackdowns and long sentences in penitentiaries. Sometimes shoulder to shoulder with police, sometimes at odds with their sworn protectors, they wade into the messy consequences of violence, drugs, imprisonment, and chronic poverty resolved to replace a war on crime with a quest for peace. In their worldview, victims and offenders do not occupy separate spheres. They share the same streets, the same struggles—often they are the same people. This more complicated reality requires strategies to address urban violence that are often overlooked by a system still in the grip of the law-and-order mentality.

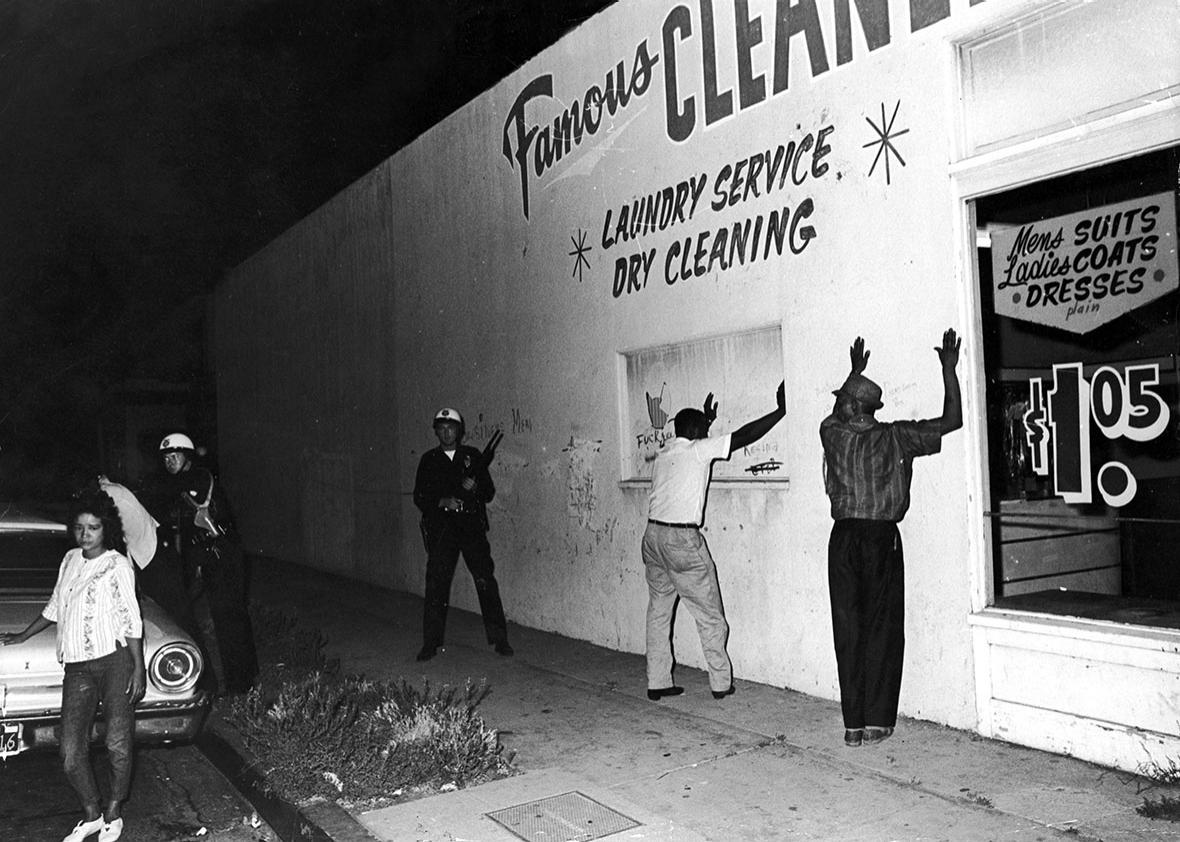

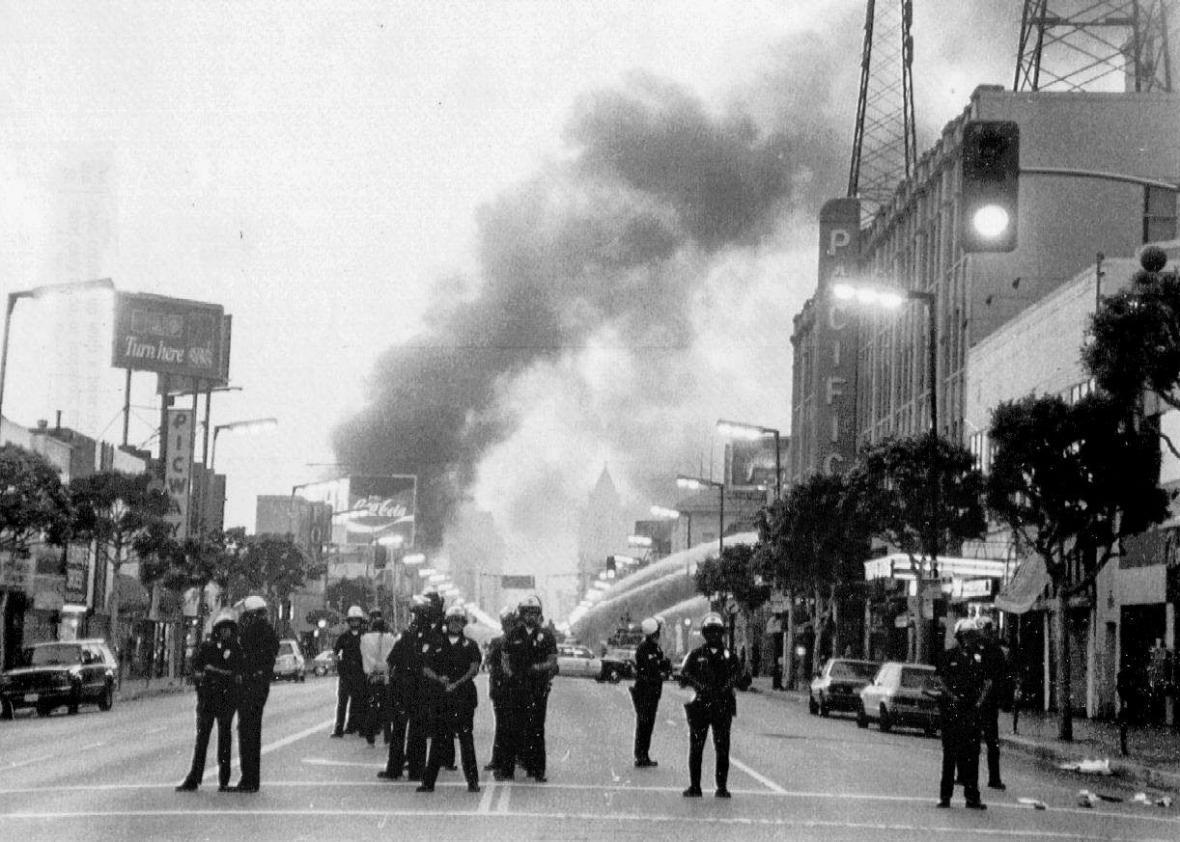

Nestled incongruously in the cradle of America’s tough-on-crime culture—“California is to incarceration what Mississippi was to segregation,” the scholar Jonathan Simon has written—is a vibrant community of activists who have spent the half-century since Los Angeles’ Watts riots honing alternative strategies to preventing crime and building community. The four pioneering groups described in this article each take a different approach to effecting change, but all root their work in supporting victims of crime. And all are keenly aware of a paradox at the heart of life in Los Angeles’s most violent neighborhoods: the perpetrators of the violence are often victims themselves.

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Cease-Fire Committee

“Welcome to the Southern California Cease Fire Committee meeting.” Ben “Taco” Owens, a former gang member who was once wounded in a shooting, sits in a circle of about three dozen other activists. He is leading a weekly meeting of a group founded a decade ago: the Cease Fire Committee. The group took its inspiration from Stanley Tookie Williams, who gained worldwide renown for his transformation from Crips co-founder to antiviolence activist before the state executed him for a series of robbery-murders. The meeting takes place in an auditorium at Bethel AME Church on South Western Avenue, a short walk from Florence and Normandie, flashpoint in the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

Photo by Dayna Smith/The Washington Post

The activists serve as an early warning system and a street diplomacy corps, gathering to share tips about what’s happening in the neighborhoods and how best to react. They come from groups promoting jobs and youth activities; pastors sit alongside police and former gang members. They each introduce themselves as “proud supporter of Cease Fire,” and many give plugs to the community organizing and violence-intervention work they’ve done for years. Among them is Adela Barajas.

Tonight’s main agenda item is a presentation by an official from the district attorney’s victim-witness assistance program, here to answer questions about aid available to victims. In the meantime, Cease Fire Committee members bring up a pair of concerns that give the lie to the notion that South Central enjoys anything remotely resembling a peace dividend, even if the city’s most violent days are behind it.

First, there’s alarm over “Internet bangin’ ”—gangs using social media in place of old-style graffiti to mark turf, stir up trouble, even to identify intended murder targets. Owens, who says he quit Facebook after seeing “things on there that disturbed me,” promises a future meeting devoted to the topic.

Next, some of the members share complaints about the constant fundraisers in the neighborhood to pay funeral expenses of those killed in the violence. “I’m tired of seeing car washes, bake sales, whatever, all of it,” says one man. “ ‘Gotta bury such and such.’ It’s ridiculous.” This “begging,” another says, adds to the shame and grief of the survivors. One man suggests a solution: encourage people to take out life insurance policies large enough to cover funeral costs. Another wryly suggests that insurance be required for gang members.

Finally, it’s time for the evening’s guest speaker, Shari Farmer from the DA’s office. She hands out thick information packets and runs down the services her department provides, hoping that these community leaders will help spread the word. Crisis intervention counseling, emergency cash assistance, referrals and vouchers for mental health counseling—Farmer’s enthusiastic presentation of these and other compensation and counseling provisions sounds like the sort of care crime victims deserve and should get. To show Farmer how dire the need for such assistance is, Owens asks the group, “How many of you in here have either been shot, stabbed, or beat down?” At least a third of those present raise their hands.

But when Farmer gets to the program’s restrictions—no help for victims the police deem uncooperative, or for anyone who contributed to the situation in which they were hurt, and nothing for those on felony probation or parole—grumbles and sighs ripple through the room. One man explains the obvious: So many of the men in the community have records that the rule is too exclusive. Another puts it plainly: You’re still a victim even if you are not a saint.

Farmer patiently repeats the rules, but then steps into an even deeper hole when she’s asked about people shot by the police. She explains hesitantly that police shootings under investigation or deemed justified are not crimes. No crime, no victim, no services.

Her words are greeted with a hush. “Wow,” one man mutters.

Farmer explains that she has to hustle out of the meeting to make another community gathering. As she leaves, she sprinkles some swag around the circle: plastic first-aid kits decorated with the DA’s logo.

One of the final speakers is LAPD Deputy Chief Robert Green, then the commander of South Bureau, which polices a large swath of South L.A. Green clearly has earned respect in this room by embodying the LAPD’s ethos of late—constructive community relations in place of its old warrior culture. He’s here this night with a plea for help after a recent spike in violence. “The problem is, we’ve got a bunch of youngsters that are shooting for the first time and so they’re full of adrenalin or emotion,” Green tells the group. “So anybody that’s got any pull at all, please do what you can. ’Cause the bottom line, I don’t want to put a bunch of handcuffs on folks and I don’t want anybody else dying up there.”

South L.A., he notes, is finally enjoying a measure of economic growth thanks to the overall decline in violence. One developer, he notes, is talking about a big retail and theater complex. “We’ll scare those folks out, and it’ll all go away,” Green tells the room. “And we can’t have that.”

Photo by Mark Obbie

Green knows that the people in this room can communicate with gangs in a language they respect and can take a message to places even a kinder, gentler LAPD can’t go. One such person is Aqeela Sherrills, a former Grape Street Crip who already was a veteran activist when his son was murdered in 2004 in a petty dispute at a party. Sherrills had launched his career in violence intervention on the eve of the 1992 riots, playing a lead role in brokering an historic gang peace treaty. Since then, he’s put more stock in community organizing than in law enforcement’s zero-tolerance approach to gangs. “The system has created this whole conceptual idea about the menacing, heartless, emotionless killers known as gangs,” says Sherrills. Only a tiny percentage of gang members commit violence, he says, while the rest are “wounded kids” desperate for a surrogate family, poverty and imprisonment having claimed their natural ones.

After his son was killed, Sherrills says he blocked his friends’ retaliation plot against the suspected shooter and instead talked witnesses into cooperating with the LAPD. The detectives never made an arrest. Sherrills wishes the killer had been held accountable but not just in the way the state defines accountability. “I hope one day I’ll be able to meet this kid,” he says. “And I’ll be able to engage in a conversation about what happened in his life that caused him to have this calloused heart.”

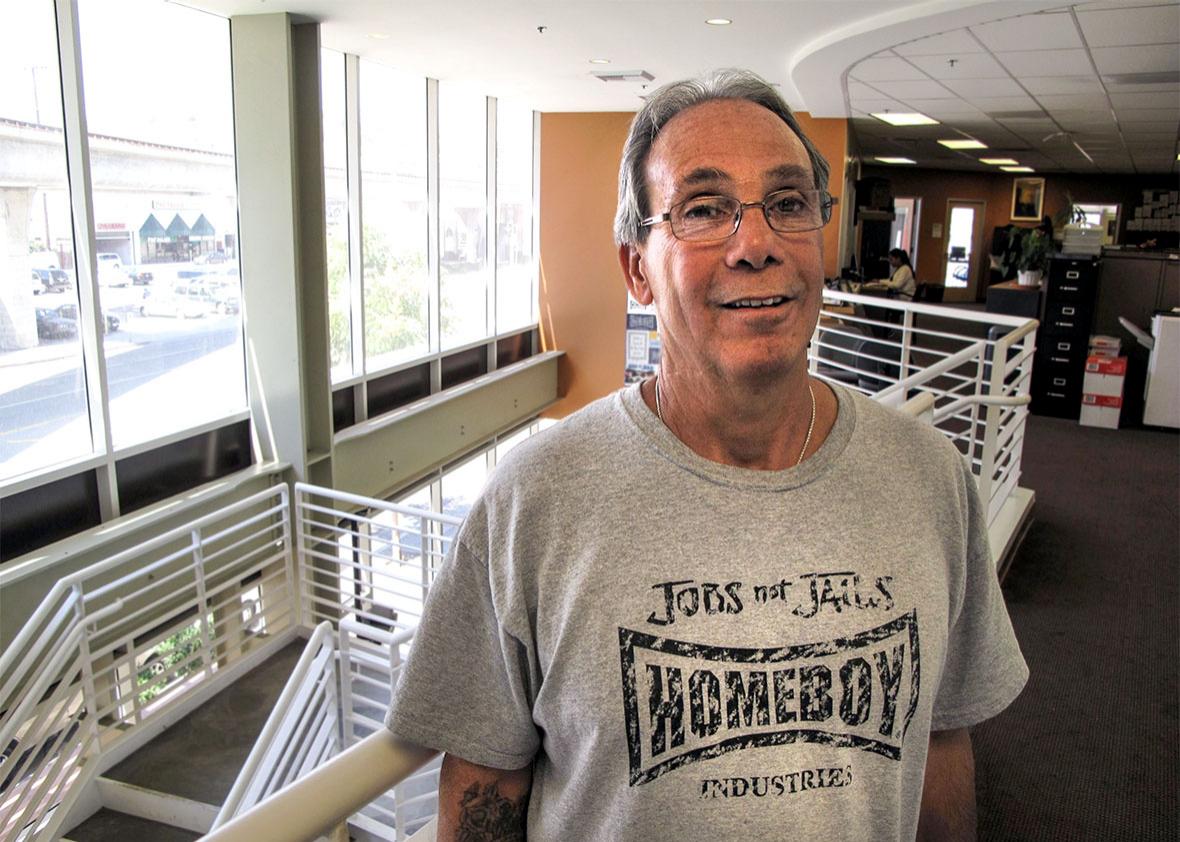

Homeboy Industries

Homeboy Industries is headquartered near downtown L.A.’s Chinatown. The nonprofit, started by a crusading Catholic priest, the Rev. Greg Boyle, hosts a funky lunch spot, Homegirl Café, and a souvenir shop selling T-shirts emblazoned with the Homeboy logo and one of its slogans, “Nothing stops a bullet like a job.” Homeboy’s social enterprise concept puts that into action by training former gang members fresh out of prison for jobs by paying them to work as apprentice bakers, cooks, and craftsmen. At the same time, it provides tattoo removal, mental health and substance abuse therapy, and closely supervised case management, all free to those lucky enough to get into the program.

Courtesy of Homeboy Industries

Boyle started Homeboy after seeing the hopelessness of parishioners at a church where he was the pastor. “I started to have to bury kids, you know?” the bearded, placid priest says in his tiny office. He has grown the organization into a major nonprofit, a $12 million-a-year operation run on grants and donations that bills itself as the nation’s largest gang intervention program.

Boyle says one of his biggest frustrations is explaining to skeptics why he’s making such an investment in rehabilitating gang members, when there are so many victims of their violence that need help, too. Boyle points out that gang violence itself is the product of victimization. “You look at those ASPCA commercials,” he says, “and they’ll have a picture of a dog who’s quite shaken and trembling and beaten up, and it will say, ‘Abandoned, tortured, abused.’ And there isn’t a single gang member who’s ever walked through these doors—not one in 26 years—about whom you couldn’t say all three. Abandoned, beaten, and abused. And so that’s the profile of why somebody joins a gang: trauma, despair, and mental health issues.”

When Boyle talks to politicians who grandly proclaim, “I stand with the victims”—here Boyle theatrically holds an imaginary phone away from his ear, cringing as he endures the lecture—he pantomimes his response with a slow, mocking clap. “It’s so dumb,” he says. “How is this at odds with that? It just isn’t. It’s just the least sophisticated take on crime at its sources.”

One Homeboy trainee, David Portillo, proudly shows me around the place. At 61, he’s older than most of the others wandering the brightly lit halls and bustling lobby. There’s a reason for that: Only months earlier he was released from prison after serving 37 years of a life sentence for murder. His story hits common waypoints: alcoholic parents, physical and emotional abuse, gangs since age 13, drugs, violence, in and out of juvenile detention. “I was broken inside,” he says.

Photo by Mark Obbie

After serving 2½ years starting at age 19 for stabbing a man who he says was beating him, he got a high school diploma and enrolled in college classes. But his friends and family were still gangbanging. One brother was killed. Portillo himself was shot and lost multiple friends to violence, including one who died in his arms. When a friend robbed and beat his pregnant girlfriend, he and other friends hunted the assailant down and killed him.

In prison, Portillo pursued education and job training, working as a welder, hospital orderly, hospice aide, forklift operator, kitchen help—wherever he could land a position. In some ways, leaving prison was harder than staying in. “I felt like the spotlight was on me. Everybody knew I just got out,” he says. “The speed of the city was too fast, too noisy. I had to get a comfort zone.”

He had no driver’s license, no credit or debit cards, no concept of computers or the Internet. But he did hold a name in his memory, having met Father Boyle years earlier in prison. On his first day out of prison, Portillo was riding a city bus that happened to pass by the Homeboy Industries’ building. He got off at the next stop, walked in, and applied to Boyle for a job. After jumping through Homeboy’s usual application hoops, including a drug test, Portillo started as a trainee custodian in Homeboy’s main building.

At any given time, there are as many as 300 men and women working full time as 18-month trainees at Homeboy. In all, more than 10,000 former gang members and their friends and family go through parts or all of the program in a year. One study of Homeboy’s recidivism rate found that 70 percent of its graduates stayed out of prison and found jobs, beating the averages by a long shot.

Courtesy of Homeboy Industries

Today, Portillo’s job as a trainee is a five-day, 8½-hour commitment. His ultimate goal is to get certified as an X-ray technician, a skill he learned in prison. He’s also learning computer basics and using his new driver’s license to deliver bread to Homeboy’s farmers market stand. At the end of August, he started his first community college classes in hopes of eventually earning a bachelor’s degree. It’s a long to-do list. But, Portillo says, “I’ve got the rest of my life to do it. Because I’m not going back to prison. Failing and going back to prison are not an option.”

Victory Outreach

It’s gang night at the Canoga Park Community Seventh-Day Adventist Church in the San Fernando Valley. At the lectern, LAPD gang specialist Sean Dinse clicks through a PowerPoint slideshow, “Hispanic Street Gangs: A violent subculture within our community,” that brims with photos of menacing gang members and graffiti tags. It’s the standard image of gang members as atavistic predators and lost causes. As he speaks to a small audience of concerned parents and church members about what lurks in their suburban community, the unspoken meaning is clear: Iron-fisted suppression is the only sane response. Cage the animals.

His fellow presenter, a local pastor, tries not to contradict Dinse while subtly making the opposite point: Gang members are looking for help and can be reached by people they trust. They might resist the pull of the gang brotherhood when given a choice. “Either you invest in their life,” he tells the audience, “or someone else is going to invest in their life.”

The pastor, Karl Cruz, knows this from experience. Cruz, 42, runs the local branch of a worldwide inner-city ministry, Victory Outreach. He’s also a former gang member whose focus is on saving as many current gang members as he can. A native Salvadoran whose family fled civil war in the early 1980s, Cruz says when he arrived at age 8 near Los Angeles, earlier immigrants from his family already were involved in gangs and drugs. “I came from a bad situation to a much worse situation,” he says.

Soon enough, he was running with a gang, drugging, robbing, and getting into rapidly escalating trouble with the law. When a young Victory Outreach member talked him into attending church services, he grasped the chance to leave the gang rather than go to prison or die.

Cruz was 16 then and has remained with Victory Outreach since. Now he has children in college and serves as president of the chamber of commerce in the town of Pacoima. When he gives talks outside of his own church, he says, he watches people subtly eye his body for tattoos (they’re hidden) and have their guard up, expecting that he’s running a con. But, when he talks to gang members, he knows how to reach them using the same tactics that worked on him. “It’s one thing when someone’s trying to tell you, ‘Hey that’s the wrong path,’ but they can’t relate to where you’ve been,” Cruz says. “And when you hear it from one of the guys that’s actually been there, it makes more sense.”

Though his approach is faith-based—he wants gang members to choose a better life grounded in evangelical Christianity—he also knows they need safety, job training, education, drug counseling, and other basic building blocks in order to stay committed. So, much of his work is connecting them to needed services and making sure they stick with them.

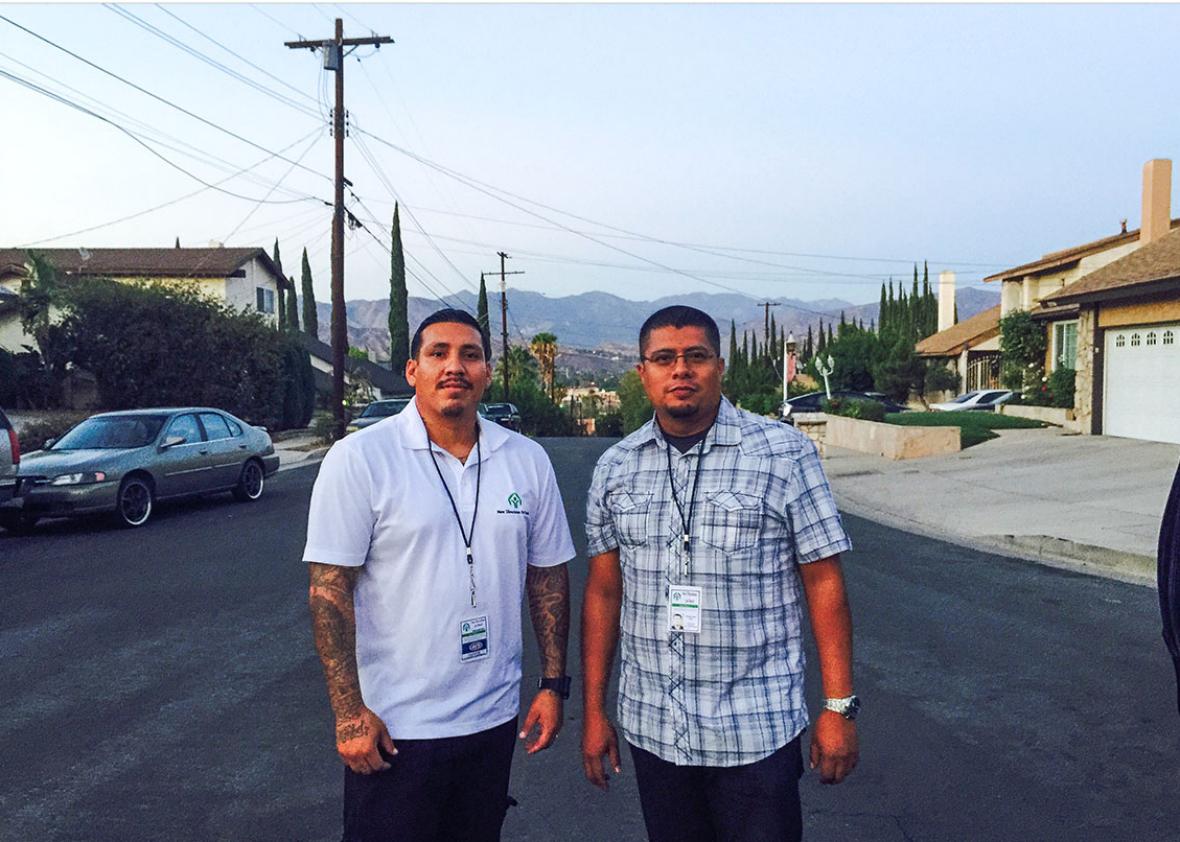

Cruz’s joint appearance with LAPD officers at the church is just one example of how he works in tandem with law enforcement. Earlier this year he won a grant from the city’s Gang Reduction & Youth Development office to counsel victims of gang shootings and their families and friends to try to prevent retaliatory violence. Cruz also works with LAPD’s nearly 5-year-old violence-intervention program using the Operation Ceasefire model (which is unrelated to the Southern California Cease Fire Committee). In that program, a pilot project in the police department’s San Fernando Valley–based Mission Area, a law enforcement team calls in gang members believed responsible for much of a neighborhood’s violence and offers them a choice: stop the violence and accept counseling and training help from service providers, or face a merciless crackdown.

As one of those service providers, Cruz takes his message to active gang members. Says Cruz, “I’ve seen guys at those meetings who break down and cry and tell me, ‘Man, I don’t know how to stop.’ ” The work is risky—gang members get “jumped in” and “jumped out,” meaning beaten or worse when they join or quit the gang—but a gang member might be allowed to walk away if what he’s doing is seen as genuine. “If you’re one of those claiming you changed and you’re still messing around, man, you can lose your life like that,” Cruz says. “But if you’re real and you’re not playing around, then you have respect.”

One former gang member Cruz tried to help, 23-year-old Jimmy Palma, tags along with his pastor at the church’s gang presentation. His round, open face and easy smile make him look anything but menacing. But Palma has his own harrowing history of violence. “I hated myself,” he says. “I thought that nobody else loved me either. So I wouldn’t do anything for myself.”

After a year in jail for grand theft, Palma was staying in a halfway house. One afternoon in May 2013, he was exiting a liquor store when he was approached by a truck full of men asking the dreaded question: Where are you from?—an attempt to learn his gang affiliation. Palma ran, but a bullet caught him in the buttocks. He nearly died from loss of blood. Fearing a worse fate if he remained in a gang, and drawn to Cruz’s promise of a better life for former gang members, Palma joined Victory Outreach. As he talks about his work to provide the same refuge to other gang members, Palma’s dedication seems genuine. Months later, however, Cruz tells me he had to part ways with Palma after his young recruit balked at following the church’s rules. Cruz doesn’t know if Palma returned to gang life, and Palma didn’t respond to texts or calls, but Cruz says the experience shows his belief in second chances has limits. “We don’t play games,” he says.

Photo by Mark Obbie

When gang members do stick with Cruz—and he boasts that at least three-quarters of his recruits succeed long term—it’s because, he says, they finally find a positive mission to replace the sense of belonging that gang life gives them.

Manuel Stopani, 29, has found that sense through his participation in Cruz’s gang intervention project. Stopani has the physical and biographic markers that earn respect in gang territory—prodigious prison tattoos and a dismal history of childhood neglect, crime, and drug addiction, culminating in nearly 11 years spent in youth detention and adult prison—but he says what resonates most with gang members is his understanding of their desperation for change. When he bottomed out, he says, “I just didn’t feel like living no more.” First came refuge in his faith. Then he cleared his mind from the fog of methamphetamine. That’s when he saw “the root of the problem, which was the condition of my heart.”

“I was thirsty for something,” Stopani says. “I wanted to become a totally different person.”

Courtesy of Karl Cruz

LAURA

In the eight years since the murder of her sister-in-law Laura Sanchez, Adela Barajas has focused her work for LAURA on two realities of her community’s condition: trauma and danger. The first devastates families if they fail to overcome a natural reluctance to confront their traumatic losses and fears. The second is the relentless conveyer belt delivering children to gangs, drugs, and violence unless someone intervenes.

On this Friday night, in a park that forms a serene oasis in the heart of South Central on Compton Avenue, Barajas is tackling that first challenge with a dozen mothers and sisters of wounded and dead young men. She promised the women a dinner and “a little event,” knowing from experience that it’s best not to reveal too much before she’s got her audience captive. Considering how many called during the day to explain the little emergencies in their lives that had popped up and would prevent them from coming, the turnout is a success. There is indeed food—a sumptuous buffet of barbecue chicken, salads, tortillas, beans, and rice—and after each attendee gets a welcome hug from Barajas and settles in around the table, they introduce themselves, all speaking Spanish.

The group’s tradition is for everyone to share the stories of what happened in their families. Newcomers are easy to spot, Barajas says: They cry the hardest. Tonight’s newcomer, Grisella, got talked into coming by her daughters, one of whom, 16-year-old Brenda, has accompanied her. (I promised anonymity to Barajas’ group members as a condition of observing their meetings, so they are identified here only by their first names.) Brenda bursts into tears as Barajas welcomes her. Later, when the conversation moves around the circle to her and her mother, she can’t even choke out her name. Grisella tearfully describes the beating her son suffered, so severe that his brain injury has blinded him in one eye. Even worse, it’s made him abusive, cursing her and his sisters, exploding in anger unpredictably. “There’s a lot of turmoil going on in the house because of the trauma,” Barajas confides later. “They don’t know how to deal with it.”

Grisella is undocumented and hasn’t sought services on her own out of fear and ignorance of the system. Barajas has been working to connect the family with a private counseling service. Tonight is one more step in Grisella’s tentative progress toward dealing with the problem instead of bottling it up and soldiering on.

After the introductions and stories of death and acceptance, it’s time for the main event. Barajas has arranged for Rita Chairez, a victims’ advocate from the Los Angeles Catholic archdiocese, to teach the LAURA survivors group meditation. Chairez started doing this work after she lost a brother to a street shooting and decided to help others to treat the anger that consumed her. Then she lost a second brother the same way. It’s a story she is practiced at telling. Now she’s helping these women warm to the idea of not just exposing their painful narratives in a small group, but of letting go of anger.

Chairez clicks the play button on a boombox. As the dinner’s Latin music playlist gives way to soothing New Age sounds, Chairez lights candles, arranges the women in two circles, and teaches them to close their eyes and breathe deeply. She reads a prayer, ignoring the wailing of a siren outside on Compton Avenue, and then at the count of three tells the women to open their eyes. They blink and smile shyly. As Chairez leads the small groups with two discussion prompts—“What has helped you when you miss your loved one?” “This is what I never like to hear.”—Barajas ushers me out to a courtyard to chat, and to give the women privacy.

One of the women’s little girls, playing outside, lurks by the door and then asks Barajas, “Excuse me. What are they doing in there?”

“They’re meditating. But don’t go in there because they’re sharing stories.”

“Of what?”

“Right now they’re sharing different feelings that they have.”

“From people that passed away?”

“Yes. From people that passed away.” With that, Barajas gently shoos the child away.

Laura Sanchez. Photo provided by the family.

One of the traditions Barajas encourages among her clients is to mark the dates most significant to their lost loved ones, the dates of their birth and death, with a cake or other celebration. “The mom remembers,” she says. For Laura Sanchez’s July 4 birthday, Barajas organizes an annual family picnic at her graveside. The family plays music and toasts Sanchez’s memory with soda or, more to Sanchez’s tastes, beer.

That, in her view, is a more fitting tribute than what the state of California arranged for Sanchez: prison sentences of 25 years to life for the four young gang members arrested, tried, and convicted in her death, and a 40-year sentence for a fifth man convicted of related racketeering charges in federal court. She supports stiff punishment for the first man who pulled the trigger, but the others who fired in the ensuing mayhem, or were just along for the ride, don’t deserve to lose their lives to prison, she says.

Barajas talked to one defendant’s aunt during one of the trials and found herself sympathizing with his family. “Having them in [prison] is not helping,” she says. “It’s destroying families. I know we have a void that can never be repaired or can never be brought back. But at the same time these families have that same void.” She’s familiar with the void from both sides. One of her own brothers is serving a lengthy prison term.

There’s nothing she can do to fix things for Sanchez’s assailants’ families. But the other part of her mission with LAURA, beyond her work with the adult survivors, is to try to reach her neighborhood’s young people before they get sucked into gang life in the first place.

Laura Sanchez with her son Brian. Photo provided by the family.

That work happens at weekly meetings at Fred Roberts Park, just up the street from the South L.A. housing project that was home base for the Pueblo Bishops gang members who killed Laura Sanchez. The park, named for a prominent black mortician in the area, was once overrun with gang members thanks to its location midway between the neighborhood’s Latino and black gang boundaries. Early in her newfound work as an activist, Barajas successfully lobbied the city to install new playground equipment and a soccer field, followed by the building of a shiny, modern community center and gym. Surveillance cameras and frequent police patrols provide better security than before. Now it’s a safe place for children and families at all hours.

Occasionally gang members show up to shoot hoops. Barajas says she tells them that so long as they behave and don’t idly hang out, they’re welcome to stay. She explains what the park is for, and the gang members get that. “Everyone that’s gang involved does not really want their younger brother or sister to be gang involved,” she says. “So I think that’s the part that they respect.”

Holding court at a freshly painted picnic table, Barajas greets people from the neighborhood. She’s dressed a little too well for the outdoor setting, in the elegant business suit she wears to her day job. She’s come straight here from work so that she can be available to talk to people about their concerns. Pointing across the street, she indicates the place where one murder occurred. The victim’s mother came to talk to Barajas, worried that another son was gravitating to gangs. Barajas explained to her how to get him into a better school. Now that mom is the school’s PTA president and works to get other parents more involved in their kids’ education and safety.

Two LAPD officers arrive to chat with Barajas and give her fliers to hand out promoting the department’s youth activities. One, Chris Ramirez, is the newly assigned lieutenant in the area. He marvels at how inviting the park looks now compared with when he was assigned as a patrol officer in this area in the early 1990s. “I got shot at here,” he mentions offhandedly. “I’m lucky I survived.”

Accompanied by a law student who volunteers her time to tutor Barajas’ LAURA youth group with their school homework, Barajas heads into the recreation center for tonight’s program: a lesson in healthy cooking. Two college students with a nonprofit, RootDown LA, are setting up cutting boards, knives, bowls.

Eventually a dozen school-age children, ranging from elementary to high school, show up. Barajas goes over upcoming events, including a weekend walk promoting peace. They go around the room introducing themselves and describing how they feel. The consensus: “tired” and “happy.”

Then it’s time to make pico de gallo and sliced fruit. Out come oranges, limes, onions, tomatoes, beets, garlic, and basil. The kids work in groups, laughing and chattering away.

A mother whose daughter is here asks Barajas if her 9-year-old son can join in. He’s below the age-10 cutoff, but Barajas agrees. Shy at first, he introduces himself and gets a lesson in chopping basil. As the pico de gallo comes together and blue-corn tortilla chips come out to sample the sauce, the boy breaks into a grin.

Barajas is pleased with how this turned out. “The kids want attention,” she says. “They’re here. They’re living. And they’re not ‘banging.’ ” As she sees things, the people who talk about gang members and criminals having made bad choices that they now must pay for is a construct that gets it exactly backwards. Gang life here is the default option. All of her work is aimed at giving children an alternative.

Outside in the twilight, boys still play basketball and families lounge on the playground. A twentysomething man on a bike turns lazy circles on a sidewalk. Just then, a police cruiser rolls by slowly, then does a quick K-turn. A light shines on the bicyclist. Two cops hop out of the car. One tells him to drop his bike, turn around, and put his hands behind his back to be handcuffed. They turn out his pockets and pat him down, raise his shirtsleeves and uncover his torso, and shine a light on his tattoos, looking for gang signs. While one officer takes the man’s ID and gets back in the car to check for warrants, the other chats amiably with the man. Barajas watches quietly. She greets a woman who walks by. “Her brother was murdered in 2008,” she says.

She watches the stop and frisk play out for 10 minutes, sighing, “This is my life.” As her youth group members leave the building, they pass by the scene showing barely any interest.

As the cops remove the cuffs and begin to leave, Barajas approaches and asks why they stopped the man. The cops say the last time they approached the bike rider, he fought them. After they leave, Barajas asks him about it. He says he was “just walking” when they detained him the last time. “I was frustrated. I was having a bad day,” he says. So he resisted and ended up in jail. This time, he showed the officers paperwork from his visit earlier in the day to his probation officer. They told him they could have cited him for lacking a light on his bicycle but decided to cut him a break.

As he gets back on his bike to leave, he shrugs. “It’s just part of my condition.”

Barajas says goodbye to the last of her youth group, gives one more mom advice on dealing with a school principal, and packs up her SUV. She has to be at work at 5 the next morning. After that, she has more LAURA work to do.