This story is part of a special Slate Plus package on Jeremy Stahl’s “The Trials of Ed Graf.” Be sure to check out another Slate Plus exclusive related to this story, a profile of the family of Cameron Todd Willingham and their campaign to have him exonerated.

The cases against Cameron Todd Willingham and Ed Graf were similar in many ways. Both men were accused of setting a fire to kill their children. Both men were accused of using accelerants to start the fire, of trapping their children in a burning building, and of not trying hard enough to save the children once the fire had started. Both men were prosecuted using forensic evidence that has since been thoroughly discredited. Both were convicted. Willingham was executed.

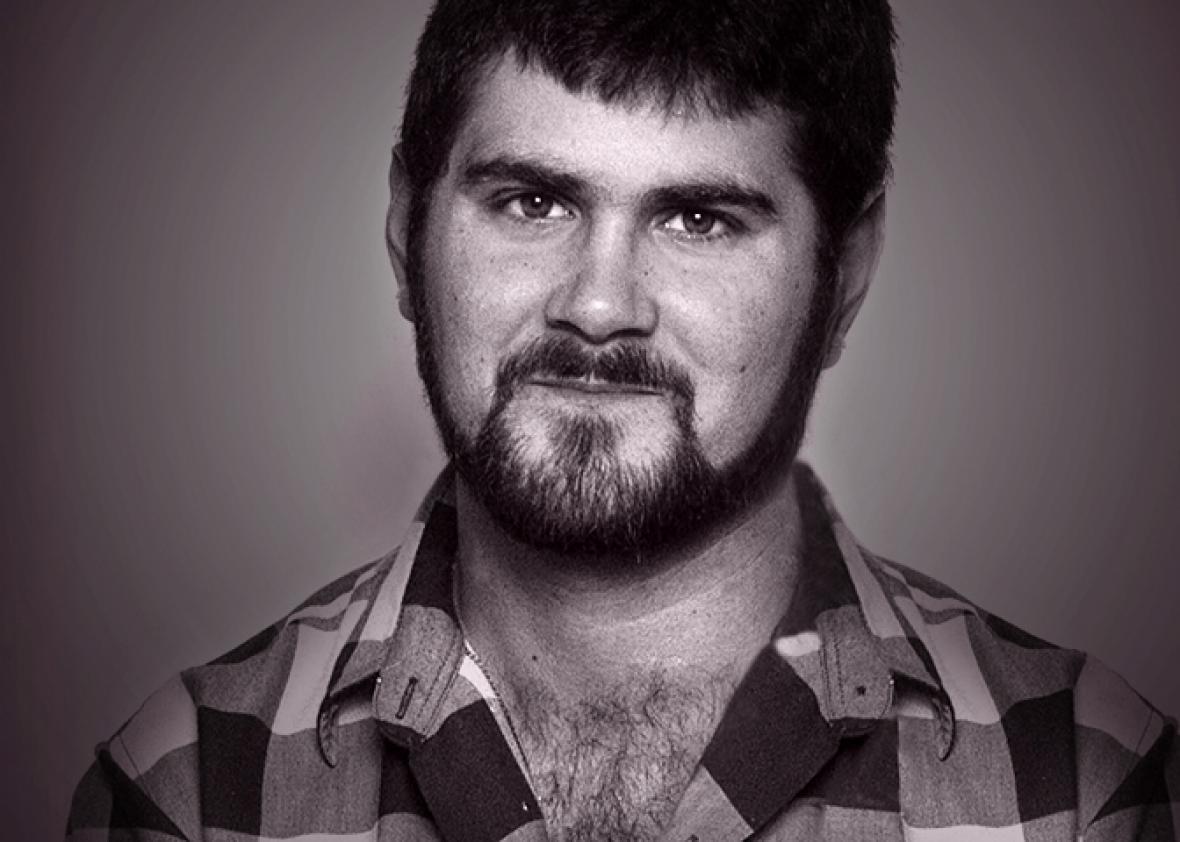

Photo courtesy of the Todd Willingham family

Arson scientist John Lentini conducted a landmark 1992 study that proved that certain supposed arson indicators could be produced in accidental fires. He was among the first forensic scientists to re-examine the Willingham case. He found there was no evidence that anyone had intentionally lit Willingham’s home on fire. At least seven other experts looked into the case and agreed. Willingham had been convicted largely on the word of two fire investigators who had claimed to find more than 20 indicators of arson. All of them were junk science.

The faulty arson science was brought to the attention of then–Texas Gov. Rick Perry and the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles before Willingham’s execution in 2004. Walter Reaves, the appellate attorney for both Willingham and Graf, sent a report by the Austin, Texas-based fire scientist Gerald Hurst demonstrating the flaws in the science. The report was ignored.

David Grann reported these revelations in his New Yorker story “Trial by Fire.” It was only then, five years after Willingham’s death, that the execution became a national scandal, drawing death penalty opponents and forensic science experts into conflict with the state’s most powerful politician.

The uproar over Grann’s story, published in September 2009, happened to coincide with preparations for a hearing of the Texas Forensic Science Commission. A prominent fire scientist, Craig Beyler, was set to testify about the flaws in the Willingham case. Two days before Beyler was scheduled to appear, however, Perry removed three members of the commission and replaced its chairman with a political ally and hard-nosed prosecutor named John Bradley. Perry was facing a heated Republican primary battle with Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison. Bradley slowed the pace of the investigation to a crawl, and the testimony wasn’t heard until after the election.

The dismissed chairman of the commission, Sam Bassett, believes his removal and replacement with Bradley were political moves meant to squelch the investigation into Willingham’s case. Bassett had been approached by the governor’s office, which argued that the commission didn’t have jurisdiction to investigate the case. Bassett decided to proceed anyway, acting on the advice of an aide to one of the state senators who wrote the bill creating the commission. Then he was ousted.

As the new chairman, Bradley quickly adopted Perry’s position that the commission’s jurisdiction to investigate Willingham was questionable. He also began parroting a line from Perry that Willingham had been a “guilty monster.”

“I think that the actions and inactions of John Bradley when he took over, and the very close alliance he had with Gov. Perry over the course of the year or so, told me a lot about what was really going on,” Bassett told me. “Frankly, [Bradley] was standing there to do a job, and that was to shut down the Willingham investigation.”

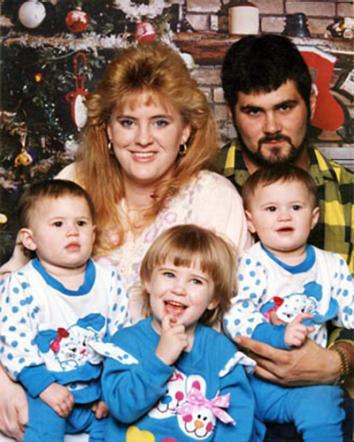

Photo by Jeremy Stahl

Bassett does not seem given to political hyperbole. He said one of his missions in chairing the forensic science commission was to include all stakeholders, “right, left, and in between,” and to make sure that it didn’t become a “pawn of the Innocence Project,” the national criminal justice reform group. He isn’t opposed to the death penalty, but he believes that it’s overused.

A number of high-profile exonerations in Texas have begun to make that opinion a less controversial one in the state. The week Bassett and I spoke, members of “the San Antonio Four” had just been released after spending about 15 years in prison on the basis of junk science.

At the time of the 2009 investigation into the arson evidence used to convict Willingham, though, the mood in the state still allowed for Perry to successfully stall the forensic science commission’s work. Both Bradley and Perry attacked modern scientific analysis throughout the slowed-down proceedings. “I’m familiar with the latter-day supposed ‘experts’ on the arson side of it,” Perry told reporters, using finger quotes.

The scientists on the commission ultimately rebelled against Bradley, rejecting a draft report that attempted to clear the original investigators who claimed to see strong evidence of arson in the fire that killed Willingham’s children. At that point, Bradley’s apparent delay tactics backfired. His reappointment to the commission failed in the Texas Legislature in 2011. He had been on the group long enough, however, to make one final, critical filibuster. Four months before his ouster, Bradley asked for a written opinion from the state’s attorney general’s office on the jurisdictional question. Perry’s attorney general Greg Abbott ultimately ruled that the forensic science commission did not have authority to review evidence that had been gathered or tested before the date of its creation in 2005.

“I really don’t think it was the intent of the writers of the statute that the commission could never look retroactively at cases,” Bassett said of Abbott’s opinion.

Fire scientist Lentini, who is less restrained than Bassett, views the whole thing as a cover-up by the former attorney general, who succeeded Perry as governor in January. “Abbott is a political hack, and he made his decision to suit Gov. Perry,” Lentini told me.

Photo by Jeremy Stahl

The ruling meant that the forensic review group could not issue an official state opinion on whether or not there was misconduct or negligence by the original Willingham arson investigators. “In my mind there was no question that there was professional misconduct,” Bassett says.

The forensic science commission did, however, issue a final report describing six indicators used in the original investigation as flawed. It also released a damning 55-page report by Beyler, the expert whose testimony was postponed during Perry’s primary campaign. “The investigators had poor understandings of fire science,” Beyler wrote. “Their methodologies did not comport with the scientific method.” The finding of arson “could not be sustained.”

Shortly after, John Bradley’s career in Texas came undone. While serving as chairman of the forensic science commission, he was also the district attorney in Williamson County, which includes major Austin suburbs. In this role, he had fought against DNA testing for more than five years in the case of Michael Morton, a man convicted of murdering his wife in 1986. The DNA ultimately was tested, against Bradley’s initial wishes, and pointed toward another suspect. Morton would be released and that other man, Mark Norwood, would eventually be convicted of killing Christine Morton. Norwood is now facing another murder charge for a similar crime that took place two years after Christine Morton’s death. (Pamela Colloff’s brilliant coverage of this story for Texas Monthly revealed the abuses that led to Michael Morton’s wrongful conviction and his being kept in jail for years after forensic evidence could have exonerated him.) The original prosecutor, who was John Bradley’s mentor, ultimately spent 10 days in jail for withholding exculpatory evidence from Morton’s defense team, an abuse that very likely allowed the real killer to remain free to murder again.

After the Morton debacle, Bradley lost his re-election bid in a landslide. Perry had been a key supporter of Bradley, taking part in a letter-writing campaign on his behalf, but it had been of no use. Bradley was soon out of a job, his reputation in tatters after a bruising campaign by the new Williamson district attorney, Jana Duty. (When Duty moved into her new office, she found a dead snake with its head cut off in her desk. Bradley denied that it had been his gift.)

He unsuccessfully attempted to get another state job and then fell off the map. In 2013, the state bar association had no information about his whereabouts. Old associates were unable to connect me with him. Finally, last summer, Bradley turned up in an unexpected place. He had landed a job as an assistant attorney general on the tiny Pacific island nation of Palau. Bradley’s appointment came months after Rick Perry had been named an “honorary consul” of the Micronesian island during a privately funded visit. Perry’s office declined to answer a Houston Chronicle reporter’s question on whether he had anything to do with helping get a new job for his disgraced political ally, the man who had squashed the embarrassing Willingham inquiry. (When I finally reached Bradley by email, he declined to comment but invited me to go diving if I’m ever in Palau. “This place has amazing reefs, coral, and sharks,” he wrote.)

At the end of 2013, Willingham’s family members and Michael Morton, who has become a prominent advocate for criminal justice reform, came together to call on Perry and the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles to give Willingham a posthumous pardon. In April 2014, the board voted to reject their plea. The Willingham family is still hoping that the new governor, Greg Abbott, or a future one will eventually grant their request.

Morton says that Willingham’s prosecutor John H. Jackson, now a retired judge, should be charged with a crime. It turns out that in addition to relying on junk science, the “second pillar” of Jackson’s case was a jailhouse informant who has since said that he was coerced by Jackson to lie on the stand and say that Willingham confessed and was ultimately offered a deal in exchange for his testimony. (Jackson, who has described the charges that he paid off the informant as a “complete fabrication,” did not respond to multiple messages requesting comment left with his law office.) The Washington Post reported corroborating evidence for the payoff claim in August. Jackson is currently facing disbarment after the state bar charged him with concealing evidence related to the informant’s testimony. (Read about the Willingham family’s continued attempt to seek justice at Slate Plus.)

Nothing can bring Cameron Todd Willingham back. There was one major consequence of his case, though. The Texas Forensic Science Commission gave 17 recommendations to revamp the state fire marshal’s office, including a proposal for it to review old arson cases where questionable science was used. Surprisingly, the state’s new fire marshal took on every single one of those recommendations. Ed Graf’s case was among the first up for review.

Read these related articles about arson investigations in Texas: