During the year since Michael Brown’s death last summer, incidents of black Americans being killed as a result of police encounters have occurred with relentless regularity. One name after another is added to the list, and with each new story, the country learns about a new set of circumstances under which a black person can die at the hands of law enforcement. While playing with a toy gun. While getting a “rough ride” after a frivolous arrest. While sitting in jail for talking back to an aggressive officer. We now know it can happen for no reason, with no warning.

The past year has forced Americans—especially white Americans—to realize that when a black person is wrongfully killed by a police officer, it’s not an isolated incident, but part of a systemic institutional failure. This has been the achievement of the Black Lives Matter movement, which coalesced into a powerful force in the wake of Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri. Today, when a black person dies in police custody in any part of the country—whether it’s Samuel DuBose in Ohio or Sandra Bland in Texas—chances are higher than ever that it will be news all over the country.

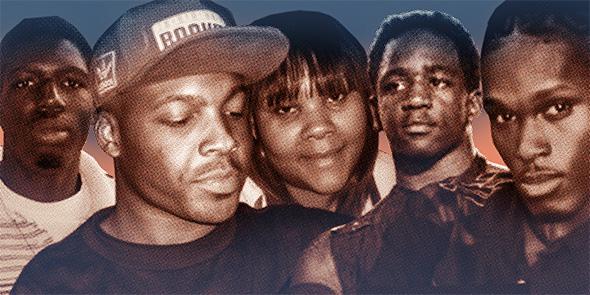

It used to be that these things happened more quietly. In April 2012, Tamon Robinson was killed while trying to run away from two New York City police officers in a patrol car. The officers say they were trying to overtake Robinson and prevent him from ducking into a housing project in Brooklyn’s Canarsie neighborhood after getting a report that someone was stealing paving stones from the street with the apparent intention of selling them as scrap.

The NYPD said the officers had intended to drive their car ahead of Robinson, in an effort to block his way to the front door of the building where his mother lived. Robinson and the car collided, and he fell to the ground with a head wound. After going into a coma, he was declared dead several days later. He was 27.

According to official police report, the patrol car didn’t run into Robinson—Robinson ran into the car, after it had stopped on the walkway leading up to the building. But residents who witnessed the episode from their windows say they saw the car hit Robinson. A few of them reportedly yelled out into the night, “We saw what you did.”

Despite those eyewitness accounts, then–Brooklyn District Attorney Charles Hynes declined to prosecute the officers. Then, a few months after the incident, Tamon Robinson’s mother, Laverne Dobbinson, was served with a $710 bill for the dent her son had left in the NYPD cruiser that killed him—an apparent bureaucratic error that briefly earned Robinson’s fate coverage in the New York papers.

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo courtesy of family of Tamon Robinson.

Robinson died during a very specific window of time: before the killing of Michael Brown by Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson in August 2014 and after the shooting of Trayvon Martin, the Florida teenager shot dead by neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman, in February 2012. It was Martin’s death, and the subsequent acquittal of his killer, that first prompted activists to start using the BlackLivesMatter hashtag on Twitter and wielding the phrase at demonstrations. But if the Martin case lit the wick, it was Brown’s death that triggered the explosion of public reckoning that would turn what began as a slogan into a full-fledged national campaign.

The 32 months that elapsed between Martin’s death and Brown’s were an incubation period—a time when millions of Americans experienced a dawning of consciousness on the issue of police violence against black people. During this brief era, awareness of what would come to be regarded during the past year as the defining social crisis of our time was on the rise but hadn’t fully registered. Many black people lost their lives in police encounters during this period, and many white police officers were allowed to walk away without consequences. And while the particulars of these encounters might have briefly made the news, neither the victims nor the officers involved became household names, and their stories were not widely held up as evidence of a national crisis.

The families of these pre-Ferguson victims have experienced the past year in a way no one else has. These mothers, fathers, siblings, and children have watched as their personal tragedies retroactively became part of a national debate not only about policing but also about the fundamental differences between being black and white in America. In the year since Ferguson erupted, they have continued to mourn their loved ones, and they have poured their grief into activism, becoming inextricably tethered to a movement that had yet to fully emerge when their family members were taken from them. In so doing, they have found purpose, as well as sorrow and disillusionment.

On a recent afternoon, Laverne Dobbinson came to the downtown Brooklyn offices of Rubenstein & Rynecki, the law firm that helped her reach a $2 million civil settlement with the city of New York over her son Tamon’s death, to talk about what life has been like since Ferguson. She had woken up at 4:30 that morning to start her job driving a van around Brooklyn, dropping off prescriptions and bringing people to their doctor’s appointments. She spoke softly, and through tears.

“People are getting out, marching, protesting about this. People are starting to care a little bit more, and realize what’s going on,” Dobbinson said. “But this has been going on for years before everyone started protesting. This was going on before.”

Dobbinson told me that going to Black Lives Matter marches during the past year, and meeting the families of other young black men killed by police, had given her strength and made her hopeful that one day law enforcement agents will stop getting away with murder. “My son’s story goes with everyone else’s,” she said. “I feel good that there are people out there who are willing to stand up with me, right beside me, and fight my struggle. I couldn’t do it by myself.”

Dobbinson was one of five people I interviewed who lost a family member to a deadly police encounter during the roughly two and a half years after Trayvon Martin’s death and before Ferguson. All experienced the past 12 months differently, though they are united by a sense that the country has, at the very least, woken up to the crisis that has defined their lives, even if it’s far from resolving it.

Calling Ferguson a “turning point,” Dobbinson said she is now seeing people who have suffered as a result of this previously unacknowledged epidemic beginning to stand up together behind an urgent rallying cry. “People are starting to go out and speak their minds,” she said.

I asked Dobbinson what she thought when she heard about the death of Michael Brown. “My reaction was: not again. Not again,” she said. “When these incidents happen, with Eric Garner, with Michael Brown—all these things are part of me.” So is Black Lives Matter, she said. “I am a part of that, and my son is too.”

“There are a lot of stories that we haven’t heard,” Dobbinson added. “But they did happen.”

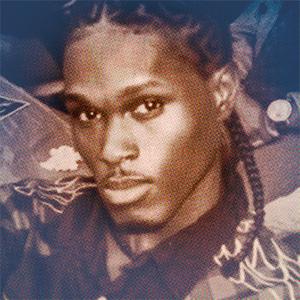

Jordan Baker: Killed January 2014 in Houston, age 26

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo courtesy of family of Jordan Baker.

Jordan Baker died because a Houston police officer patrolling the area outside a strip mall saw him in a parking lot and determined that he fit the description of a robbery suspect. Baker was wearing a black hoodie at the time, and according to the official police account, he charged the officer who was trying to detain him and reached for his waistband after a brief foot chase. It was at that point, police say, that the officer fired his gun and killed Baker, who was unarmed.

Baker left behind his mother Janet, and his young son, known in the family as Little Jordan. When I called Janet Baker last week, she told me she remembers attending a town hall meeting in December—shortly before a grand jury declined to indict the officer who fatally shot Jordan—devoted to discussing whether Houston could become the “next Ferguson.”

“I’m sitting in the room and they’re having a whole discussion about, ‘Could Ferguson happen here?’ ” she said. “And I’m sitting there crying the whole time, thinking, This was in your city and you have no idea. Ferguson has already happened here.”

Baker said she never saw the police as a potential source of danger before her son was shot. She understood them to be protectors, not threats, even after Jordan told her about an officer who pulled him over and shouted at him while Little Jordan cried in the back seat. Baker’s general attitude when it came to racism was to be conciliatory, she said. Her desire was always to smooth things over and keep the peace.

“I’m always overly trying to make people feel comfortable,” she said. “I’ve done it all my life. … Because the micro-aggressions, they exist—I’ve lived them. And when I know a person feels a certain way, I counter it with a lot of calmness. It’s exhausting.”

Baker said she taught the same approach to her son and told him that as a young black man, it was his responsibility to counter the assumptions that people might make about him. Jordan believed his mother was naive to think simply keeping quiet in the face of racism would make it go away. “He told me … ‘No amount of your positive spin is going to change them,’ ” Baker said. “And I remember that conversation we had, and I was quiet because I didn’t want to in any way negate his feelings or be dismissive of the way he felt.”

“Now, looking back, I’m so heartbroken,” she said. “Because I feel like I’ve apologized all my life.”

When Trayvon Martin was killed, Baker says she felt a gulf between her view of what happened and that of her white co-workers. “I was surprised to hear people saying anything other than, ‘Wow, that young man was just executed,’ ” she said. “I was really shocked that anyone could see it any differently.”

Later, watching the George Zimmerman verdict at a relative’s house, Baker remembers her grandnephew asking why Zimmerman had been acquitted. “The look on his face when he was asking this, it was just a blank empty stare,” Baker said. “Because, what was that saying to this little boy? ‘I’m not safe here.’ And then, not long after, for his cousin, my son, to be shot three blocks away from his home.”

Last year, when it was announced a few days before Christmas that the grand jury tasked with investigating Jordan’s death had found no evidence that a crime had been committed, his mother felt herself instantly connected to the families of Eric Garner and Michael Brown, whose loved ones had also died at the hands of police officers who were not punished for what they did.

“My life was changed forever,” Baker said. “And the national attention has given me hope. But I have to be honest: I’m afraid, because it’s almost as if [it’s] a pot with the lid on it that’s about to boil. There are just so many people who are affected.”

“This is my new life,” she added. “I try to study every police-involved encounter and officer-involved shooting now. … Hopefully something will come to fruition.”

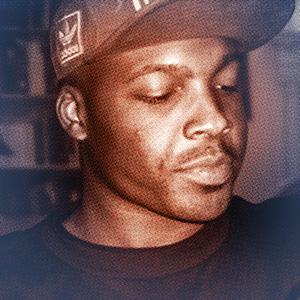

Victor White III: Killed March 2014 in Iberia Parish, Louisiana, age 22

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo courtesy of family of Victor White III.

Victor White III was buying cigars at a gas station when a fight broke out outside. Later, he was stopped and frisked by a police officer who mistakenly suspected him and his friend of being involved in the scuffle. White was placed in handcuffs before being searched again; this time he was found to be in possession of a small amount of cocaine.

White was dead within hours; according to the officers who arrested him, he shot himself while sitting in the back of their squad car, while handcuffed, with a gun he had allegedly managed to conceal from them during the two pat-downs.

White’s father and namesake, the Rev. Victor White II, does not believe his son’s death was a suicide. He notes that the officers’ original report had him shooting himself in the back, though the Iberia Parish coroner later showed that he’d been shot in the chest. Though the coroner maintained that Victor III’s death had been a suicide, his father can’t fathom how a person could shoot himself in the chest while his hands were cuffed behind his back, and he doesn’t understand why his son would have wanted to kill himself, even if it had been physically possible. “My son did not kill himself,” the Rev. White was quoted as saying at the time. “He was full of life. He was working. … He was about to move into an apartment. How could he kill himself? He had too much going on.”

The Rev. White told me he knows that most Americans don’t know his son’s name. He ascribes this anonymity in part to the fact that there was no video of his death, as there was in the cases of Eric Garner and Walter Scott. (Even with Michael Brown, the Rev. White noted, there were the chilling images of his lifeless body lying in the street for four hours after Darren Wilson shot him.) But it was also a matter of timing: If Victor III had been killed after Ferguson, his father said, he believes it would have received more national attention, and “they would have known about it from New York all the way to California.”

The Rev. White says he feels a connection to the Black Lives Matter movement but believes it has not moved the needle in the South the same way it has elsewhere in the country. “Even now,” he said, “it hasn’t come to that point in our community. Nationwide there has been a movement but here in the South, [police brutality] is so commonplace that it’s seen as acceptable. … It’s very difficult to get a movement going, because it’s been going on, and nothing is said about it. It’s an everyday occurrence. … There has not been a rallying call as of yet.”

White said it pains him that his son’s story does not come up when the issue of police brutality is discussed at the national level. “It’s heartbreaking—I tell you, it sucks the air out of me. I get exhausted just thinking about it. Even when they mention the things that have occurred, they don’t mention my son in the same light. … They’re out there talking about it—it’s just that my son’s name is not being mentioned,” the Rev. White said.

In October, he hopes to stage a Black Lives Matter rally in honor of his son in New Iberia, Louisiana. “I pray that a connection is made,” he said.

Rekia Boyd: Killed March 2012 in Chicago, age 22

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo courtesy of family of Rekia Boyd.

Rekia Boyd was killed when an off-duty police officer driving through the West Side of Chicago at night got into an argument with a group of people—including Boyd—standing in an alley and thought he saw one of them—not Boyd—pull out a gun. While sitting in his car, the officer fired five shots over his shoulder into the group of people, hitting Boyd in the back of the head. (The only object that was later found on the individual who provoked the officer to fire his weapon was a cellphone.)

The Cook County state’s attorney charged the officer with involuntary manslaughter, but he was acquitted in a bench trial under bizarre circumstances.. The presiding judge declared that the prosecutors had essentially accused the officer of the wrong crime: Because the defendant had pointed his gun at his intended victim and fired, it should have been considered an intentional act, and the charge should have thus been first-degree murder. On that basis, the judge decided not to convict the officer, who could not be retried due to double jeopardy protections. This strange chain of events was explained by attorneys not involved in the case as a brazen example of a prosecutor protecting police from accountability.

Martinez Sutton, Boyd’s brother, had grown up feeling wary of the police. When he was 8 years old, he and his friends were frisked by an officer in their neighborhood, and when someone asked what they’d done wrong, the officer hit him in the back of the head and told him to shut up. As he got older, Sutton told me, “there never was a day that went by I didn’t see a group of guys on a car” being searched. “It became an everyday norm. I thought it was normal—police stopping us, frisking us, asking us questions, sometimes fighting us. It was normal to me because I seen it so much.” Some officers were known for being especially aggressive, he said—they had nicknames like Supercop and Cowboy. Sometimes these officers would pick Sutton and his friends up, ask them questions they didn’t know the answers to, and then drop them off, as punishment, in a part of town where they were at risk of being attacked by gang members.

Despite his experiences, Boyd’s death and the way it was handled by the Chicago Police Department came as a shock. “I didn’t know people who had been killed by police,” Sutton told me. “When my sister was killed, it opened my eyes to the bigger problem. I didn’t know the police were as ruthless as they are.”

Sutton has since become a police brutality activist who speaks regularly at conferences and rallies around the country; he has a special focus on female victims, who he believes don’t get enough attention from the media. Boyd’s death, in particular, he felt, didn’t have the kind of impact it should have. “People were still on Trayvon Martin when it happened,” he said. “They weren’t noticing that there were a lot more brothers and sisters getting killed right behind that. I won’t really blame the people. It’s more so that the media didn’t push it out there.”

During the past year, Sutton feels Americans have started to think more clearly about police brutality, which has allowed him to make up for some lost time in terms of getting his sister’s name out into the world.

“When the death of Mike Brown happened, people exploded,” he said. “They were already tired of what was going on. They were ready to snap and I think that just did it—to see this mother and father in pain, it was like, ‘We gotta do something.’ ” He went on: “Everything has a time and place. With Rekia’s case, she didn’t get that mass media attention—she didn’t get a movement. It was well hidden within the community.” Nowadays it’s different: “I feel a lot better. Everywhere I go now, folks come up to me and say, ‘We’ve been hollering your sister’s name.’ Just letting me know she didn’t die in vain.”

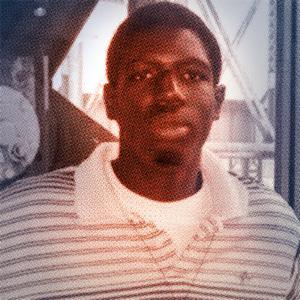

Kendrec McDade: Killed March 2012 in Pasadena, California, age 19

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo via Kendrec McDade/Twitter.

Kendrec McDade’s mother moved away from the neighborhood of Pasadena where she had grown up because she wanted to protect her children from the police. “It was fear of death,” Anya Slaughter told me. “The fear of them killing me or killing my friends, or falsely incarcerating me. Abusing us.” She knew the family of Howard Martin, a 22-year-old killed by a police bullet in 1992, and wanted to escape the neighborhood in order to protect her family from the same fate.

But her son Kendrec ended up losing his life in the same exact part of town that his mother had tried to escape. The incident began with a late-night 911 call placed by a man reporting that he’d been robbed by two men armed with guns. Two officers in a squad car spotted McDade nearby shortly thereafter and gave chase. After a brief pursuit, the two officers shot McDade a total of seven times, later saying that the teenager had charged one of them with his hand at his waistband. McDade, it turned out, was in fact unarmed, and the 911 caller admitted that he had lied about his assailants having guns. The officers involved were later cleared of any wrongdoing by the FBI, and the L.A. County district attorney declined to prosecute them.

McDade’s mother has been trying to make something positive out of her loss. She told me she is trying to launch a foundation that will pay for kids to play football, as McDade did, and is hoping to make a documentary about her son’s life, and possibly write a book.

Looking out at post-Ferguson America, Slaughter said she sees the problem of police violence getting worse, not better. “It’s becoming unbearable,” she said. “I think the police are getting comfortable with it. I think it’s happening more.” She said she feels scared lately to leave her home. “Activists are getting murdered now; women are getting murdered now,” she said, referring to Sandra Bland, a Black Lives Matter supporter who is believed to have committed suicide in a Texas jail cell last month. “Right now if the police pulled behind me, I wouldn’t stop—I would be scared to stop.”

I asked Slaughter what it’s like to know her son’s death is now part of something bigger—a movement, however nascent. “What do you mean, how does it feel?” she said. “It doesn’t feel like pride—none of this feels like pride to me. This is a horrible tragedy that I’m dealing with. This is something I don’t want to deal with. … This is something that I have to step in to do, to try to get justice, not only for me but for other people. I didn’t choose this.”