Prison slang is forged under pressure. A word that means one thing on the outside can mean something entirely different when used by people leading highly restricted lives in cramped, often dangerous facilities. Inmate shorthand can be indecipherable even to the family members who come to visit them, and it can vary greatly from one institution to the next.

Before they set about compiling a dictionary of prison slang, the inmates at Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center in Bonne Terre, Missouri, used words like viking (meaning a prisoner with poor personal hygiene) and Cadillac (meaning a cup of coffee with cream and sugar) without thinking about it too hard. But when a group of inmates put their private language under a microscope, they realized the way they use language reflects years of institutional history and serves as a unique window onto their experiences of prison life.

The dictionary—which I first heard about thanks to St. Louis Public Radio—came about as part of a prison education program operated by Saint Louis University and was conceived by English professor Paul Lynch, who volunteers at the Bonne Terre prison, a medium-/maximum-security facility. Inmates opted into the project by signing up for a class and worked on the dictionary with Lynch during two-hour sessions once a month.

Lynch said he introduced his students to the idea of creating their own dictionary by having them read part of Simon Winchester’s The Meaning of Everything, a book about the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary. The idea, Lynch told me, was to show the inmates that a dictionary is not a book of rules but a description of language as it is used in real life at a particular moment in time. “The goal was to make the students see language as something more fluid and evolving than they’re probably accustomed to,” he said.

Step one was to distribute a bunch of index cards to everyone in the class and ask them to write down any words they used on a regular basis that they thought outsiders wouldn’t understand. Lynch asked that each word be accompanied by a definition and an example of how it might be used in a sentence; at the end of the exercise they had a master list of several hundred words. In order to make their task more manageable, they whittled the list down to about 60 words by identifying the ones that were most specific to life at Bonne Terre. That meant more generic terms like shank or the hole were discarded. “Anything that you learn from watching Shawshank Redemption we threw out,” as Lynch explained.

What happened next was essentially a series of classroom debates among inmates: about proper usage, what certain words really mean, and whether some were too outdated to be included. “Guys would get really worked up about it, in a very friendly and constructive way,” Lynch said.

These impassioned discussions revealed, among other things, the generational fault lines that divided the inmate population. There were certain words, Lynch said, that older guys knew that younger ones didn’t and vice versa. As a 51-year-old inmate named Stuart Grebing told St. Louis Public Radio, “Whether in softball or in handball or at the weight pile or whatever, you hear a conversation go on and you’re lost. You don’t know what they’re talking about.”

“One term we debated was dun-dun,” Lynch said, explaining that it was short for dungeon and referred to the prison segregation unit, where inmates are kept in solitary confinement. “Only the older guys had any memory of that word being used that way, so we wondered whether we should even include it, because it seemed to be almost gone. But we decided to include it with a note saying that it was almost obsolete.”

Another controversy involved the term 12/12, which refers to the date when an incarcerated person becomes completely free—meaning not just out of prison but off parole as well. “There was a big debate about how that word got used grammatically,” Lynch said. “The question was whether or not you should say ‘What’s your 12/12?’ versus ‘What’s your 12/12 date?’ Some guys said that was redundant. But others said, if you’re working with younger guys who are just learning the administrative ropes, you had to be more clear.”

Some slang was off limits for the project. “We avoided anything having to do with the—how would you say it—the uglier side of prison life,” Lynch said. This was in part because prison officials would not have been happy to see slang related to sex and violence in the dictionary but also because the inmates who participated in the project probably didn’t want to share or publicize words they depend on to conduct under-the-radar business.

“I think there are terms they did not share with me,” Lynch said. “I don’t know what these terms are. But any surveilled population develops a language in part to hide certain things.” Prison workers know this, obviously, and this glossary of terms compiled by a Texas correctional officers union suggests that attempts are made to systematically monitor the code words inmates are using to communicate with each other.

The completed Bonne Terre dictionary now sits in the prison library. And while Lynch declined to share a copy of it with me, he did offer some of his favorite entries, which you can read below.

kite, n.: An informal message sent by a prisoner. According to Lynch, this is a word that has been picked up by correctional officers at Bonne Terre as well. “It’s not uncommon for a supervisor to say, if you have an issue with something, ‘just send me a kite.’ ”

two-for-three, n.: Used in bartering, as in “Let’s do a two-for-three: I’ll give you three bags of chips later if you give me two now.”

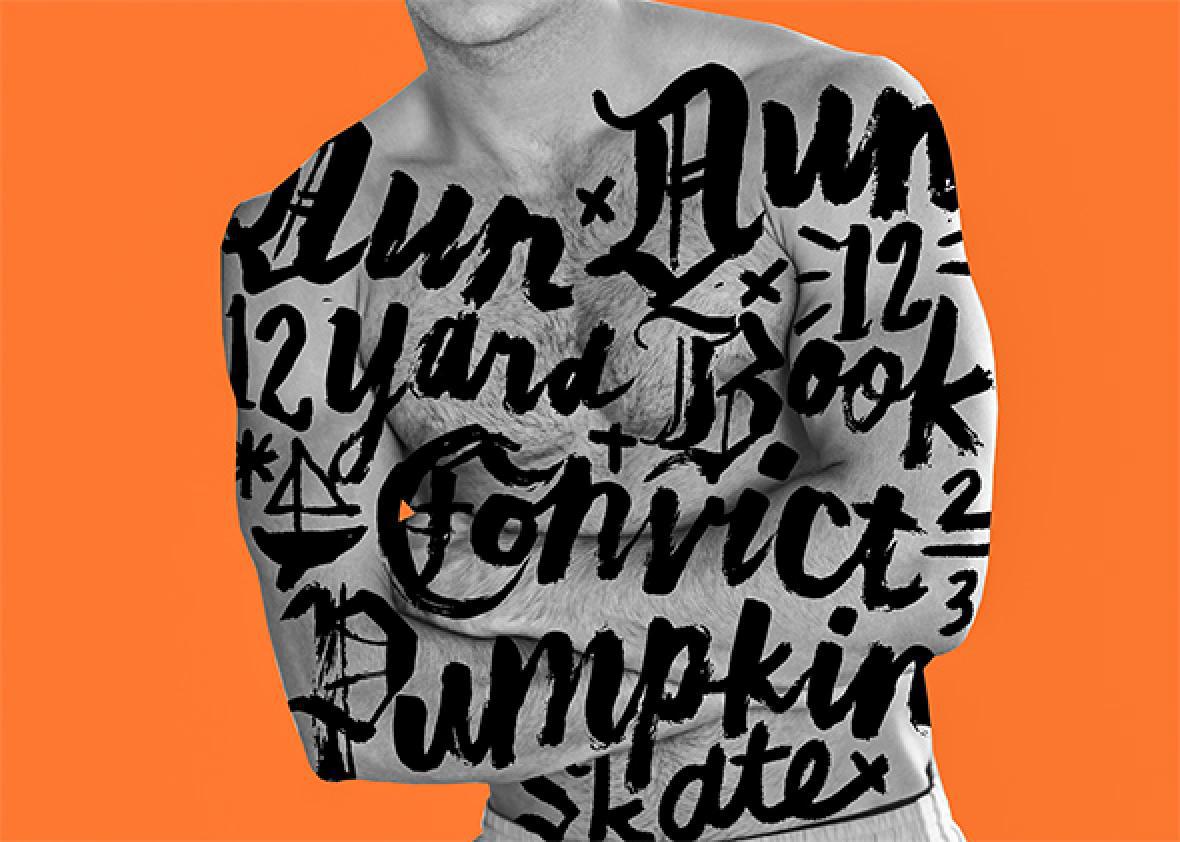

convict, prisoner, inmate, n.: These three words are used to distinguish between people based on how long they’ve been incarcerated and what level of respect they’ve earned. A convict is someone who’s been around the block, knows how to carry himself. An inmate is someone who’s new and green. Prisoner is neutral.

jail, v.: Refers to being skillful and considerate in one’s approach to being a prisoner or cellmate, as in “That guy doesn’t know how to jail.”

skate, v.: To be somewhere you’re not supposed to be, as in “I was skating yesterday afternoon and got caught.”

boat, n.: A plastic bed that is used when the prison is overcrowded.

pumpkin, n.: A term used for new arrivals at Bonne Terre because they wear orange jumpsuits instead of the gray and tan ones that inmates get after they’ve been processed. (The area where new inmates are processed is called the pumpkin patch.)