This is the third installment in a series on victims of crime. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

On the second day of the Federalist Society’s annual National Lawyers Convention last fall, former U.S. Attorney General Michael Mukasey opened his segment of a panel discussion with a joke: “And now a word from the Luddite wing of the panel.” Mukasey was one of four criminal-justice experts on stage for what was billed as “a conversation among conservatives” about criminal justice reform. The subject was a draw for this crowd, considering how many leaders on the right now champion ideas that a short while ago would have been considered categorically liberal. Mukasey was included to bring symmetry to the panel: It was him and one other tough-on-crime traditionalist debating two advocates for reform.

When Mukasey took a crack at making the “Luddite” case, however, the strongest opposition he could muster to the flurry of pending reform measures was a plea to advance cautiously toward big cuts in imprisonment. That left it to his teammate, William Otis, to go it alone in defending the sentencing status quo. After a blunt opening volley—“Two facts about crime and sentencing dwarf everything else we’ve learned for the last 50 years: When we have more prison, we have less crime. And when we have less prison, we have more crime”—Otis continued as his side’s only resolute oarsman, pulling with all his might against the current.

It’s a role Otis has grown accustomed to. In congressional hearings, seminars, and news stories heralding the bipartisan reform movement and the practical inevitability of changes in federal law, Otis serves as the go-to voice for maintaining tough-on-crime sentencing.

Pundits, policy wonks, academics, and journalists seem in lockstep agreement that there really is no debate anymore about whether it’s time to pull back from the extremes that gave America its distinction as the world’s prison warden. As names like Meese, Gingrich, and Koch speak up on the other side of the divide, Otis seems increasingly isolated, the only man fighting a war that ended a long time ago.

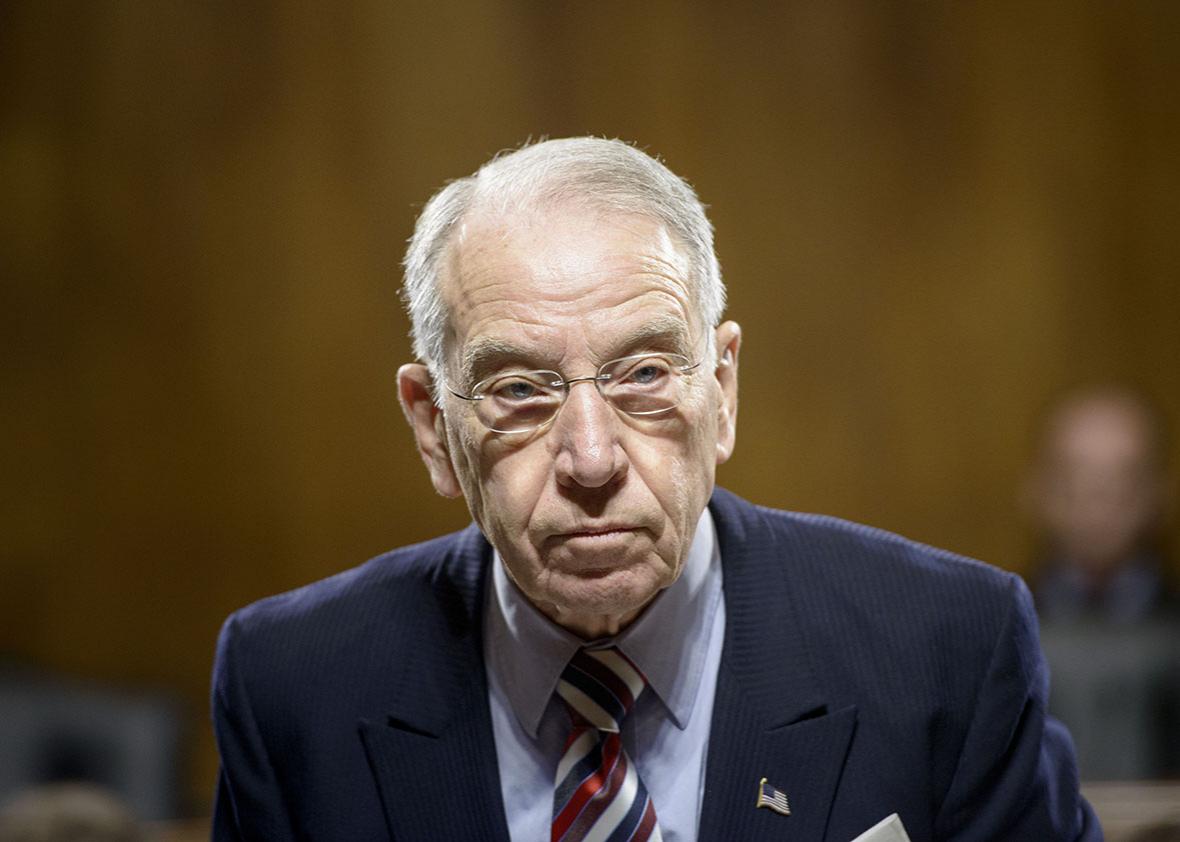

But there are compelling reasons—strategic and substantive—not to count Otis and his views out just yet. For all the talk that criminal justice reform has finally reached critical mass, the last Congress failed to act, even when offered the low-hanging fruit of the Smarter Sentencing Act, which would only tinker modestly with the length of sentences for nonviolent drug offenses. This week, Iowa Republican Chuck Grassley, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee and a longtime opponent of reform, signaled that he would finally bow to pressure from all sides and deliver a bipartisan reform bill by the time Congress takes its summer break. But a wide gulf surely separates Grassley’s version of reform from practically everyone else’s, and none of the proposals before Congress are more than a tentative first step toward undoing decades of harsh sentencing policy. Reformers’ best-case scenario is a long slog ahead, with Otis and his arguments dogging their every step.

That’s because Otis’ significance goes beyond machinations in Congress and straight to the intellectual heart of our mass-incarceration problem. Thanks to a pugilistic writing style and willingness to meet all comers in the ring, he best articulates the political thinking that put crime victims at the center of tough-on-crime advocacy. The recent conservative embrace of criminal justice reform has fueled breathless media reports about an unstoppable, bipartisan movement. Otis is banking on the mass appeal of a simpler message, one that has held sway for four decades now: that any retreat on harsh sentencing would be a threat to safety and an insult to victims.

Reformers are the media darlings of the moment. But until they find a way to counter Bill Otis’ victim-centered rhetoric, they’ll be little match for the tough-on-crime camp’s last true believer.

* * *

With a hawklike visage and a bellicose speaking style that makes every utterance sound like a poke in the chest, Bill Otis seems at first like a sharp-edged man who brooks no backtalk. One on one, though, he can display a disarming modesty about how he found himself playing the part of crime fighters’ chief defender.

The standard shorthand bio for Otis emphasizes the credentials that journalists and those organizing panel discussions and hearings rely on for legitimacy: career prosecutor, legal academic, assignments at the tip of the spear in the war on drugs. It’s all true, but Otis cheerfully admits there’s less to it than meets the eye.

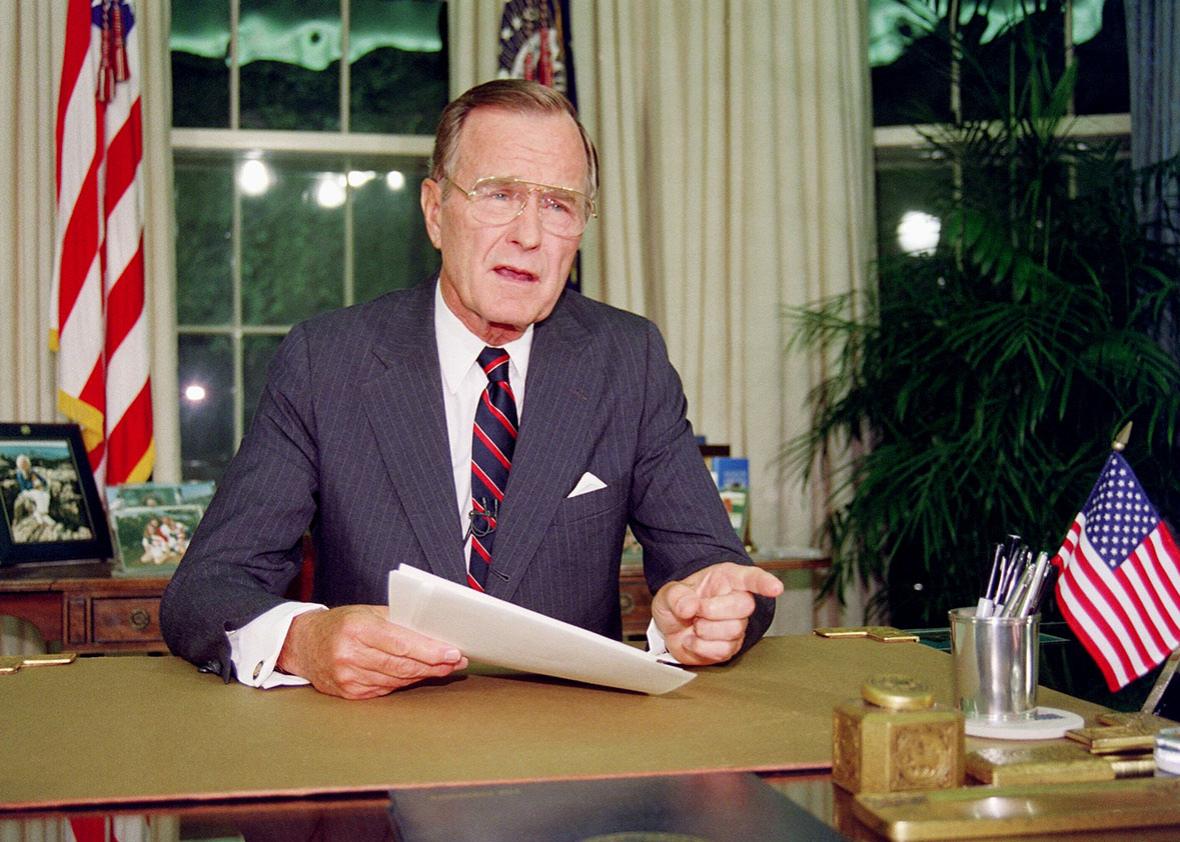

In 25 years with the Justice Department, Otis never tried cases. He toiled, instead, as an appellate lawyer, his nose buried in books and briefs. He ended up in the White House counsel’s office near the end of President George H.W. Bush’s term, dispatched there to temporarily lend a hand to a harried office. “I turned out to be the person they could spare” at Justice, he says. “It was dumb luck. It wasn’t that I was any big star.”

Photo by Luke Frazza/AFP/Getty Images

After deciding that his early retirement in 2007 had come too early, Otis took up teaching, writing, and policy advocacy. Now 69, he co-teaches one class at Georgetown University’s law school, Conservatism in Law in America, with his wife,Federalist Society co-founder Lee Liberman Otis. Other than his modest stipend as an adjunct instructor, Otis notes, “I’m not working for anybody. No one is paying me. I don’t make a cent from doing this. I just kind of have a bee in my bonnet. And in order to get the bee out of the bonnet, I write.”

Otis’ writing typically appears not in prestigious research journals or policy magazines, but on a blog that bills itself as a rare voice for “criminal law issues from the perspective of victims of crime and the law-abiding public.” It’s there, on the Crime and Consequences blog of the California-based Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, that Otis found his springboard into quotable prominence just as sentencing policies crafted in the 1980s and ’90s—his specialty at the Justice Department—turned into justice reformers’ primary target.

In the world according to Otis, “pro-criminal” advocates want to restore discretionary power to the “robe-wearing partisans” of our courts, dragging society back to the bad old days of judicial leniency and uncontrolled violence. They would finish dismantling the federal sentencing guidelines, of which Otis was an early champion. They peddle the “cultural mush” of excuses rather than individual responsibility and due punishment. Naive faith in mercy will mire America in “doubt, decline, and retreat” just when tough sentencing has brought crime down to more acceptable levels. To Otis, sentencing reform means being “nice to drug pushers” who will roar back to full strength should we recalibrate mandatory minimum sentences in the slightest. Fiscal arguments—that continuing the prison-building boom is unsustainable—exaggerate the price of prisons while ignoring the added welfare costs that are inevitable once prisoners are set free.

Faced with the choice between two potential errors—continuing to imprison someone who’s no longer a threat and releasing someone who ends up harming new victims—Otis says he’ll opt for the former. “Error is an inevitable fact of life,” he says in an interview. “And the only realistic question that adults can ask is not what system are we going to adopt that is going to avoid error, because there is no such system. The only question you get to ask is, which system is going to give us the fewest errors and who should have to bear the risk of error?”

Though Otis usually eschews the theoretical vocabulary of criminologists for more pungent terms (a favorite device of his is to refer sarcastically to offenders as “Mr. Nicey”), the philosophy he gravitates to has a name: incapacitation. It holds that a surefire solution to crime is to remove likely offenders from society. Otis’ version of the idea embodies what Berkeley law professor Jonathan Simon calls “a kind of axiomatic success that is immune to empirical evidence.” If any parolees commit crime, well, there you go: case closed. And if locking them up is the only true insurance against future crimes, then the best crime prevention measure is locking up more people for longer sentences. Rather than see dramatically declining crime rates as cause for corresponding drops in imprisonment, Otis argues that now is not the time to tinker with a successful formula.

What about the research-based consensus that the decades-old practice of mass incarceration cannot take much credit for the drop in crime, and that the strategy long since passed the point of diminishing returns? Or the growing body of evidence that crime declines even as incarceration rates do, too? Otis generally dismisses inconvenient crime studies as agenda-driven propaganda from liberal advocates and academics. Believing them, he vows, will reward us with the same “national crime wave” that we got as payback for 1960s-style rehabilitation programs. The answers, he says, are found in common sense, not the literature of sociology and criminology: Punishment simply works.

* * *

Many of Otis’ fellow conservatives have abandoned this as an article of faith, for a variety of reasons. Fiscal hawks and small-government advocates see imprisonment as an unaffordable and ineffective government program. Libertarians oppose aggressive policing, overcriminalization, and mass incarceration as abuses of power. Evangelicals preach the gospel of second chances.

Cracks in the tough-on-crime wall have appeared even among the most stalwart advocates: prosecutors’ lobbying groups. One of the few advocates who could be counted on in recent years to match Otis quote for quote, National District Attorneys Association director Scott Burns, has been replaced by Kay Cohen, who has shown herself to be far friendlier to reform.

David LaBahn, an NDAA veteran who now runs the smaller Association of Prosecuting Attorneys, says his members take a “mend it, don’t end it” view of mandatory minimum sentences. But they want to be a part of the conversation about making rational cuts in sentences for all but the most serious violent crimes. Throwing the book at criminals, says LaBahn, does little to help the victim. “The guy that gets his car stolen really doesn’t care whether the person gets a weekend, six months, or 25 years. That individual wants their car back. If the car has been damaged, they want some restitution.”

Otis gamely takes on his growing body of dissenters in panel discussions, testimony before subcommittees and task forces in the House and Senate, and in the media. (He regularly serves as The Other Side in sentencing reform stories in the New York Times;for example here, here, and here). But among reform advocates frustrated over their failure thus far on Capitol Hill, Otis has acquired a reputation as a player, not just a pundit—a trusted source in congressional staff briefings, adept at helping craft the arguments that have jammed the gears of federal criminal justice reform legislation.

Exactly what role Otis plays is the subject of intense speculation among reform advocates, many of whom believe that Otis has the ear of Grassley. (None would say so on the record out of fear of alienating Grassley and his staff.) Though Grassley said this week that his committee would endorse a bipartisan reform bill, its scope and ambition remain a mystery. While advocates may be heartened that Grassley may finally be coming around, they should see what he’s offering before doing too much crowing. Up until this point, the Iowa Republican has vigorously opposed reform at every turn. When the Senate Judiciary Committee was in Democratic hands last year, Grassley failed to defeat the Smarter Sentencing Act in committee but waged a successful campaign to block a floor voteuntil the clock ran out on that Congress.

Grassley’s power over the fate, and form, of Congressional action makes Otis’ longtime relationship with Fred Ansell, Grassley’s key criminal-policy aide, an envied platform as the debate proceeds. Otis will say only that he has known Ansell for many years, and both men refused to talk about any discussions they have had about pending legislation. A spokesman for the Iowa senator said that “Senator Grassley’s positions are not informed by just one or even a small handful of sources.”

Photo by Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images

Otis claims that whatever influence he has comes from his ability to write what many others are thinking—that, he says, “would not make me Rasputin”—and because he’s practically the last man standing on his side. “I am one of the few academics—I may be the only vocal academic—that takes a pro-prosecution view of this,” Otis says. “So it’s not that I’m any great genius or it’s not that I have friends all over Capitol Hill. It’s that I’m the only place to go.”

None of the denials discourages ideological opponents from seeing what Douglas Berman of Ohio State University once called Otis’ “very significant and cloistered role in seeking to derail any new federal sentencing reforms.” Berman bemoans what he calls a “cloak-and-dagger” approach to policymaking. Why not admit, he asks, that Otis speaks for traditional crime-policy thinkers who have largely fallen silent in the face of the reform movement’s outspokenness. “He’ll go out there and articulate the tough-on-crime position as forcefully and as aggressively as anybody that I can think of,” Berman says. “I’m sure the Lindsay Grahams and Mitch McConnells of the world don’t want to say, These new kids advocating for federal sentencing reform don’t know what they’re talking about. But Bill can say that with less political fallout and more of an ability to help the establishment craft their message.”

Berman admits his only evidence that this is what is going on is that “just about everything Bill Otis says shows up in a Grassley floor speech a few days later.” There’s some tantalizing proof of that. Earlier this year, for example, talking points from Otis blog posts—attacking a New York Times editorial on reform, calling out reformers for claiming to target only “low-level, non-violent” offenses, and praising arguments by then-DEA chief Michele Leonhart and the Washington Post’s Charles Lane—appeared shortly afterward in Grassley speeches on the Senate floor in March and May. As smoking guns go, though, it’s not quite enough to refute Otis’ claim that he is, at most, “a minor league [George] Will or [Charles] Krauthammer on sentencing issues, because I too get read.”

On at least a couple of occasions in public, however, Otis hasn’t been quite so demure. Last year he bucked conventional wisdom at the time to confidently predict the defeat of the Smarter Sentencing Act in a guest post on Berman’s blog. When challenged by a commenter for proof, Otis replied: “My info is not from statistics or a study. I know people you don’t, and who are better positioned to know than any statistics or study would be. That’s as much info as you’re going to get. … Where I get my information about the lay of the land in Congress is none of your business. If I started naming on the Internet the people in this town who talk to me, they wouldn’t be talking to me very long, now would they?”

During the Federalist Society debate last November, legal writer Kenneth Jost asked the panel for predictions of what a Republican-controlled Congress would do to give that bill and others another shot. Otis gave a stock answer, noting Grassley is “one of the leading voices against the Smarter Sentencing Act and I anticipate that under his excellent leadership any moves to dumb down our sentencing system will have some trouble.” To that he added a sly look and knowing nod, drawing laughter from the Washington-savvy crowd, which took his point. Otis wasn’t guessing.

Photo by Scott J. Ferrell/Congressional Quarterly/Getty Images

When I suggest to Molly Gill, government affairs counsel for Families Against Mandatory Minimums, that reformers’ confident talk doesn’t match the results thus far, and that they’re still struggling to counteract politicians’ fears of being labeled soft on crime and anti-victim, she says, “I think we’re approaching the tipping point. I think we’re very, very close to a tipping point. But that said, there’s still a lot of hearts and minds to tip.”

* * *

As reformers work to win those hearts and minds, they frequently come up against the position that has long been Otis’ fallback when confronted with evidence that we can decrease imprisonment and crime simultaneously: It’s not about the criminals, it’s about the victims.

Victims have been at the heart of sentencing policy since the 1980s. The most successful campaigns to get tough have been framed as tributes to victims—“Megan’s laws” for sex offender registries, three-strikes laws inspired by victims like Polly Klaas, John Walsh’s crusade in memory of his murdered son Adam. Generations of who-can-be-toughest-on-crime politics have sprung from resentments over a justice system perceived as lax and loophole-ridden. The logic—justice for victims means punishment for offenders—is so thoroughly baked into our politics that it’s rarely examined or questioned.

Otis describes harsh sentencing as the ultimate victims’ issue, and claims to be speaking up for victims at a time when their voices have been drowned out in the media by calls for reform. “Crime victims have nothing like the voice raised in behalf of criminals,” he wrote in a comment thread on his blog last fall.

“It’s not that we have too many prisoners serving sentences that are too long, but that too many criminals are released too early.”

In Otis’ telling, reformers’ zealous and misguided efforts to show mercy for criminals is an insult to victims and an invitation to further harm. The nature of criminality, he argues, hasn’t changed—“when a thug belts you to grab your purse, you still have a knot on your head and no purse; and when Mr. Nicey rapes your eight year-old, you still have a defiled little girl to try to help.” But thanks to the new reform climate, criminals can now hope to find themselves in front of “a bunch of judges newly at ease in snickering at crime victims”—judges who are more concerned with the rights of the perpetrator than of the victim.

In Otis’ view, harsh sentences not only show respect for the victims of crime but also prevent criminals from finding new victims to prey on: If a criminal is incarcerated, he can’t do further harm. “When they’re in jail, they’re not ransacking your house in order to get money for their next fix, assaulting your college-age daughter on a meth-fueled high, or selling PCP to your teenage son,” he writes in a typical blog post.

Otis’ gestures toward victims—and his conjuring of scary scenarios in which parolees run wild—are canny strategies, especially when you consider this poll and many like it, which reveal that the public remains largely unaware that we’re decades into historically steep drops in crime. Which explains Otis’ self-assurance when confronted with what the media too often describes as a growing consensus surrounding reform. “There’s a consensus among cozy interest groups and academic leftists. Talk to the man on the street, and it’s a different story,” he wrote in one blog post. In another, he observed: “Polling confirms what common sense and experience tell us: The public overwhelmingly thinks that the problem in the criminal justice system is not that we have too many prisoners serving sentences that are too long, but that too many criminals are released too early.”

A handful of reformers have begun challenging the notion that sentencing reform is by definition antithetical to victims’ interests, and have proposed reinvesting savings from shrinking prisons in improvements to victims services. For the most part, though, the criminal justice reform community has all but ignored victims, leading to what David Kennedy of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice has called a “catastrophically misguided” divide. On one side, militaristic retributionists who claim an exclusive hold on victims’ interests. On the other, softhearted reformers focused on prisoners’ welfare. It’s law as war versus law as social work.

One reason reformers often leave victims out of the policy conversation is due to an unavoidable reality of victimization: The automatic response, at least when the wound is fresh, is to seek the maximum punishment as justice. Vengeance is instinctive, and it finds expression in extreme prison sentences.

By tuning that instinct out, reformers believe they’re championing reason over emotion. That, says drug policy theorist Mark A.R. Kleiman, doesn’t work. Any 3-year-old “will cheer when the victim retaliates,” he notes. “The sort of law professor/liberal politician view of this is that the demand for vengeance is atavistic,” Kleiman says. “If you were a highly evolved being, you wouldn’t worry about that. Bullshit! Every crime is an insult as well as an injury.”

Kleiman is an unapologetic critic of harsh sentences. But, unlike most reformers on the left, he believes the solution lies in finding more effective forms of punishment, not just seeking less of it. He believes that we need change but acknowledges that the penalty for getting it wrong will indeed be more people falling victim to violence.

Photo by Leigh Vogel/WireImage

In his book When Brute Force Fails: How to Have Less Crime and Less Punishment, Kleiman argues for punishment that is swift and certain rather than severe. Instead of the prevailing model—a feedback loop of sending huge numbers of people to crime-breeding prisons for increasingly long terms, only to release them eventually to prey again on the most vulnerable citizens—a smarter system would dole out punishments evenly and fairly, and in proportion to the crime. Kleiman’s recent thinking has focused on shortening sentences but finding new ways of strictly monitoring parolees and punishing all violations swiftly but fairly.

In Kleiman’s view, the excesses of three-strikes laws and mandatory minimum sentencing have given punishment a bad name. Once we accept the essential role of retribution in our justice system, we can have a more rational debate about sentencing policy. “If we stop being embarrassed about retributivism,” Kleiman says, “we could then try to make it proportionate.”

The ideal system would combine crime prevention with minimally necessary punishment; or, at the very least, replace a maximalist mindset—defining anything less than the most draconian punishment as an insult to victims—with a renewed commitment to making punishment proportional to the crime.

Before Congress will even think about structural changes on that scale, it’s concentrating on relatively small-bore adjustments to the existing system—while all but ruling out re-examining sentences for violent crime. Even that is too much change for Otis. He referred to Obama’s recent overtures to the reform movement as “the President’s Criminals-Are-Cool” campaign, and he criticized Obama for visiting a federal prison, arguing that by viewing criminals as victims, reformers ignore the real victims: “those living in the most crime-ridden areas.” In another recent post, Otis asked when the media will ask “normal people” whether the system is as broken as the reformers would have it. So far, his taunts have gone unanswered.

This is the third in a series of articles on the victims of crime and the ways in which we fail them by focusing criminal justice on harsh punishment alone. Sign up for alerts about future installments below.