The first weekend in May was an eventful one in Marin County, California. On Friday afternoon, in the hamlet of Forest Knolls, sheriff’s deputies received a call about a gold Lexus that had been discovered with blood inside. That evening, in the nearby town of Lagunitas, the Sheriff’s Office learned of a man with curly blond hair and missing front teeth who was threatening to shoot someone’s dog. Later that night, shortly after 1 a.m., a man with two children was seen preparing to take a green canoe out onto Tomales Bay. And on Sunday afternoon, a woman in Woodacre who had locked herself out on her deck was heard crying out for help after trying to climb a tree.

Each of these incidents was reported in the police blotter of the Point Reyes Light, a small weekly newspaper that has served the communities of West Marin, an otherworldly ocean-side stretch of land that lies beyond the Golden Gate Bridge, since 1948. In the same issue, the paper carried items about clumsy children (“STINSON BEACH: At 2:45 p.m. a 7-year-old fell off the lifeguard tower, hurting her arm”), restless animals (“FOREST KNOLLS: At 5:15 a.m. someone had been listening to a dog bark for an hour”), and concerned parents (“MUIR WOODS: At 2:12 p.m. a woman wished to talk about ‘inappropriate stuff’ she discovered on her child’s phone”).

The Light, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1979 for its reporting on a local cult, publishes a few dozen such items each week as part of its Sheriff’s Calls column. The column, which is written by the paper’s editor-in-chief, Tess Elliott, chronicles the worries, fears, misfortunes, and mischief that prompt the residents of West Marin to alert the authorities. It is the best police blotter in America, or at least the best one I’ve ever read.

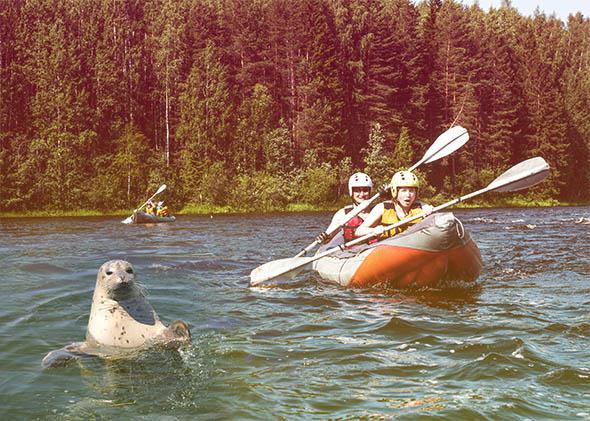

Sheriff’s Calls items tend to run no longer than 40 words, and they range in subject matter from the trivial (“BOLINAS: At 2:49 a.m. someone complained about loud hot-tubbers”) to the disturbing (“WOODACRE: At 9:51 a.m. a woman reported finding the body of her cat with a broken back in her backyard. She believed her son had killed it, and was afraid he would now go after her dog”). Some are about intoxicated or otherwise disturbed people (“BOLINAS: At 3:22 a.m. someone heard a group of drunk people near Smiley’s. The people later told deputies they would wrap it up”); some are about family disputes (“BOLINAS: At 9 a.m. a man and woman were heard swearing at each other over a dog that had died during the night”). Many prompt more questions than they answer (“MUIR BEACH: At 11:31 a.m. three men in suits were knocking on doors, asking if people spoke French”), while some shimmer with the particularities of Northern California life (“DOGTOWN: At 1:59 p.m. someone said two kayakers were harassing seals in the lagoon. Deputies found them acting within the law”). Taken together, they conjure a detailed portrait of life in West Marin, especially the lives of its unluckiest, and nosiest, citizens.

BOLINAS: At 3:08 a.m. a woman who had taken a taxi home from a hospital reported that the taxi driver had become stuck in a ditch outside and was now yelling at her.

STINSON BEACH: At 7:49 a.m. a ranger asked for help with a woman who was having problems with an innkeeper, though he or she was notably vague about it.

FOREST KNOLLS: At 11:20 a.m. a farm stand owner reported receiving an anonymous letter criticizing his high prices.

Newspapers typically publish police blotters that are written either with an absence of style or an overwhelming amount of it. In the first category, you have papers like the San Jose Mercury News (sample item: “1200 block of Sesame Drive, 9:30 a.m. May 5 Cash and jewelry were stolen from a residence. Entry was made through an unlocked rear window”). In the second category, you have proudly hammy papers like the New York Post, which occasionally slather their crime reports with hardboiled slang. (A recent Post item starts out, “A straphanging sicko groped a woman in a Bedford Park subway station, police said.”)

The Point Reyes Light goes its own way, delivering its blotter with a deadpan detachment that nevertheless manages to convey mood and emotion. The column is by turns sad and funny, precise and mysterious. Reading it is a bit like eating a bag of assorted, subtly flavored jellybeans.

STINSON BEACH: At 8:04 a.m. two bicycles disappeared through a back door, leaving tracks in the sand.

SAN GERONIMO VALLEY: At 10:07 a.m. a deputy smelled smoke on Nicasio Valley Road, then walked through the redwoods and found a stump covered with smoldering embers. He took a picture of it to deliver to firemen.

Elliott became the Light’s editor in 2007, and has written the Sheriff’s Calls column since 2008. Now in her mid-30s, she arrived in Marin County after growing up in Oregon and studying writing at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. (The university was founded in 1974 by an exiled Tibetan monk; the poetry program was started with the help of Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman.) She didn’t have a background in journalism, but the Light’s publisher at the time hired her anyway.

Writing the Sheriff’s Calls column initially required Elliott to go down to the sheriff’s substation in Point Reyes and copy the details of each incident report out of an actual logbook while deputies walked around and gossiped nearby. Nowadays she gets a daily email from the Sheriff’s Office, with each incident labeled according to when and where it happened.

“The dispatchers are taking these calls and they’re jotting down notes, which are then announced over the radio system that they use,” Elliott explained to me. Not all the incident reports come from 911 calls, she added. Some are nonemergency calls placed to the Sheriff’s Office (“POINT REYES STATION: At 4:50 p.m. a red wallet had been left in a porta-potty”), while others seem to be based on in-person reports (“FOREST KNOLLS: At 4:20 p.m. a resident asked for advice about a neighbor whom the caller said had been harassing him for the last 12 years”).

When Elliott sits down to compose the column, she pulls from the source material tangible details about the individuals involved while protecting their privacy—a measure she calls “a gesture to people’s dignity.” In general, she told me, she makes a point of leaving out certain pieces of information that other police blotters might include—the address of the home where a crime was committed, for instance—but she still strives to produce something useful.

“Countless bits of news, from arrests to deaths to boat accidents to neighborly disputes, are included in the log, without which most would never be reported to the public,” Elliott wrote to me in an email, noting that the police blotter, as a form, has always provided a public service. In principle, at least, that purpose is to spread the word about bad actors in a community, and perhaps to explain suspicious situations that residents may have noticed unfolding in their midst. For instance, a number of people in West Marin have complained over the past few months about hoax phone calls to their homes from identity thieves pretending to be from the IRS. This information seems useful for Light readers to have so that they know not to fall for the scam themselves. There are also a lot of calls about teenagers being rowdy on the beach and having bonfires. It’s possible this comes in handy for parents: If your kid says he’s going to a sleepover at his friend’s house, ask for details.

The column also captures changes afoot in a bucolic area that was, in the past, safely distinct from the city across the bay. Nowadays, tech billionaires are settling among the hippies, and tensions between old and new residents sometimes bubble up:

BOLINAS: At 9:58 a.m. a realtor reported that her home had been egged and her sign broken; she suspected someone might have been mad that she was selling property in an area where many locals cannot afford to stay.

The majority of the items that appear in Sheriff’s Calls, however, could not be said to possess any news value, or even any real usefulness. This is either because they’re plainly insignificant (“STINSON BEACH: At 11:48 a.m. rocks were lying in the road”), deliberately vague (“POINT REYES STATION: At 5:16 p.m. someone died”), or clearly personal (“FOREST KNOLLS: At 10:35 a.m. a woman called to say she and her husband were separating amicably but that he had threatened to take their kids to Germany”).

Elliott acknowledges there’s a tension in her work between service journalism and art. “The fact is that I’m not a journalist by training, or probably by nature. I am rather preoccupied by feelings, impressions, styles and human drama, and I care too much about the beauty of things,” she wrote to me. “So I guess you could say my artistic nature disrupts the utilitarian drive that I still identify with as an editor.”

The Sheriff’s Calls are arguably at their best when they are narrative-driven, though the narratives are of a very specific sort: never fully contextualized, and usually unresolved. As Elliott wrote to me in an email, the Calls recount “everyday stories, some trivial, some tragic, but always pointing to the fragility inherent in the human condition.”

LAGUNITAS: At 5:53 a.m. a janitor reported arriving at the lower campus [of the local school] to find three youths sleeping in front of a classroom door. Deputies later learned it was part of a plan by students hoping to surprise their classmates.

BOLINAS: At 1:55 a.m. a man getting a cup of coffee while fishing in the lagoon reported seeing a Mustang crashed into a hillside.

These are stories with no beginning or end, narratives perpetually frozen in the middle. We don’t know exactly what kind of prank the students were planning to pull, or whether they were allowed to pull it after being discovered by the janitor. As for that Mustang, the best we can do is hope that everyone in it survived.

Sometimes the uncertainty is almost too much to take, as with this melancholy report from Christmas Eve 2014:

FOREST KNOLLS: At 6:51 p.m. a parent reported a possible restraining order violation involving the caller’s son and a green Ford Ranger parked at the saloon.

Was it the spirit of the season that moved this young man to come home and try to make amends with his family? Was he waiting inside the Ford Ranger when the deputies arrived on the scene, or had he gathered up his confidence by then and knocked on his parents’ door? The item leaves the reader holding on to very little, but just enough.