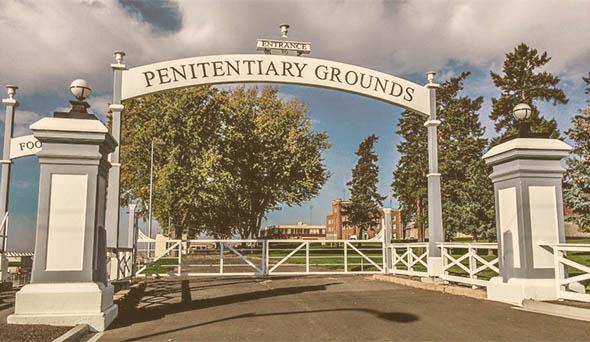

When Bernie Warner started as a correctional counselor in the segregation unit of the Walla Walla State Penitentiary in Washington 35 years ago, the inmates he oversaw were considered lost causes. They were in solitary confinement because they were seen as the worst of the worst—irredeemable monsters with irrepressible violent tendencies that led officials to conclude it was too dangerous to keep them with the prison’s general population.

Today, Warner is the senior-most executive in the Washington state prison system. But he still remembers his days at Walla Walla, a period that he says instilled in him a belief that “how people are treated in the deepest end of the correctional system is what really defines it.” The experience inspired Warner to try to reinvent what segregation can be—an effort that in just a few years has produced one of the most humane approaches to solitary confinement in the country.

“Washington state is a real innovator and has been something of a pioneer on these issues,” said Allison Hastings, a senior program associate at the Vera Institute of Justice, a nonpartisan think tank that was brought in to consult on the Washington program in 2010.

The initiative stands out for being geared toward rehabilitation, with correctional staff administering behavioral courses to groups of inmates in small classrooms instead of keeping them in lockdown 23 hours a day, as is typical in segregation units elsewhere. The classrooms, which you can see in this video, were built in three separate Washington prisons; one was converted from a lieutenant’s office, and the other two used to be food pantries. Because the inmates taking the courses are considered extremely dangerous, they are restrained at their desks with shackles but allowed enough room to move around that they can turn toward each other and participate in role-playing activities designed to teach conflict resolution and the social skills required to deal with other people peacefully. Hastings, who has observed the courses, remembers watching as inmates were asked to imagine themselves in various scenarios, like standing up for a friend who has been insulted or threatened by another inmate without resorting to violence.

To date, the Washington program has resulted in an almost 50 percent drop in the number of people the state keeps in isolation: from 612 in January 2011, when the program for violent inmates started, to just 286 last month. It is premised, Warner told me, on the idea that every prisoner, even the so-called worst of the worst, deserves a chance to improve himself, instead of being left to waste away in a tiny, windowless cell with no human contact for months or even years.

As hard as it is to fathom for those of us on the outside, forcing people to live in such isolating conditions is the standard approach that jails and prisons around the United States take when locking people up in solitary. And while the past several years have seen reforms enacted in multiple states, the practice remains almost unthinkably routine, with an estimated 80,000 Americans being held in segregation units at any given time. In recent years, questions about whether this state of affairs represents systemic, government-sponsored torture have become hard to ignore, with multiple civil rights lawsuits being filed and gut-wrenching media reports—like the one published in last weekend’s New York Times Magazine about a supermax prison in Colorado—giving the public a vivid understanding of just how destructive life in solitary can be to a person’s psyche.

Solitary confinement in Washington prisons used to be more or less like everywhere else. The changes since 2010, when Warner took a leadership position in the state’s Department of Corrections, have their roots in research conducted by a team led by David Lovell, then a professor at the University of Washington and now the research director at the California Board of State and Community Corrections. In an email, Lovell told me he found that once inmates entered solitary, they stayed for an average of nearly a year because of rules designed to keep potentially violent and self-harming inmates out of the general population. (For context, there are cases of inmates being held in solitary for as long as 28 years. But a person doesn’t have to be in for nearly that long to start experiencing hallucinations, chronic depression, and suicidal thoughts.) Lovell and his colleagues also found that a quarter of inmates with experience in segregation who were released from prison during their study left directly from a solitary confinement cell—meaning they were going directly from total isolation to freedom with nothing in between.

One of the goals of the courses being administered now is to prepare inmates for life on the outside: “Ultimately 95 percent of them will be released into the community,” Warner said. “And it’s part of the public expectation that prisoners return to the community less of a public safety risk than when they enter. So that means you have to present opportunities for them to change their behavior, whether it’s based in criminal thinking, or chemical dependency, or mental health issues.”

A defining feature of the Washington approach is to divide people with different problems into different programs, all of which operate out of separate prisons.

In Walla Walla, violent offenders with possible gang ties are coached in suppressing aggression. In the Monroe Correctional Complex, mentally ill inmates with inclinations toward chronic self-harm are put through group therapy and stabilized through medication. In the Clallam Bay Corrections Center, people with nonviolent behavioral issues and impulsivity problems are taught self-control and coping mechanisms. Dan Pacholke, the deputy secretary for Washington’s Department of Corrections, half-jokingly referred to the three groups as “bad, mad, and sad.”

“If you’re developing a strategy on how you’re going to get them out of segregation, you have to understand why they’re in there,” Warner said.

You also have to figure out how to motivate inmates to improve. That means rewarding good classroom behavior with opportunities to sign up for more group programs on subjects like parenting and faith. It has also meant trusting some inmates with custodial jobs that require them to interact with members of the general population. “We’ll let a person out to sweep or mop or clean counters,” said Pacholke. “We’ve used program participants to do that. As with any behavioral change approach, you have to have incentives, and so there are, even within segregation, incentives that can hopefully trigger positive behavior.”

While there are a few other states that have implemented “step-down” programs aimed at moving people in segregation out into the general population, the Washington model has attracted national attention from advocates and other correctional executives. But replicating the model in other prison systems will not be easy—in part because it can be hard to get buy-in from prison staff, many of whom view segregation as their only tool for dealing with inmates who would otherwise not think twice about attacking them. Convincing the prison staff in Washington to become enthusiastic about the new approach to segregation took time, according to Eva Kishimoto, a research associate at the University of Cincinnati Corrections Institute, which was brought in to Walla Walla to train officers and other staff members in administering rehabilitation courses.

“At the beginning we had some staff who were really skeptical about doing it,” Kishimoto told me. “But once they started seeing the violence levels in the segregation unit go down, we started getting more and more staff interested in being a part of it.”

Warner praised his staff for getting on board as quickly as they did. Still, it was a gradual process, and a lot of effort went into making sure that the participating inmates didn’t put each other or the staff at risk. This meant rehearsing the process of transporting inmates from their cells into the classroom before there was even any curriculum in place, Kishimoto said.

Despite these challenges, the success Warner and his team have had in reducing the number of people in solitary has attracted interest. Since the program got going, Warner said, Washington has hosted groups of prison officials from nine other states who wanted to know more about the approach.

“I’d hate to portray this as, ‘We’ve solved the problem,’ ” Warner said, noting that he doesn’t believe it’ll ever be possible to obviate the need for solitary confinement entirely. “I don’t know if the number ever gets to zero, but that’s not our goal. Our goal is to manage inmates safely in the least restrictive environment possible.”

Kishimoto said she hopes to see that attitude adopted more widely. “If what we’re doing elsewhere in the country is just warehousing people, I think we’re spending a lot of dollars and not getting what we could out of it,” she said. “We could either have these people leave prison angry, being more vindictive and less capable, or we could have them leave prison with a different kind of attitude and a different set of skills. And these are guys I would not want leaving prison without having had the opportunity to get that kind of treatment. Because they’re going to be walking down the street where my daughter works or where my grandkids go play at the park.”

In a political climate that still demands extreme punishment when it comes to violent offenders, it could be that the way to make rehabilitation a core part of solitary confinement in more prisons is to frame the change in terms of public safety. Treating the “worst of the worst” more humanely and with more faith in their potential to change is not just for them—it’s for us, too.