When the Department of Justice revealed in early March that the police department in Ferguson, Missouri, had been systematically targeting black residents with onerous fines for minor violations, the first question many people asked was: Where else is this happening? Is Ferguson an outlier, or one of many cities around the country where such abusive and racist police practices are being employed?

Advocates for police reform were quick to say there were “other Fergusons” all around us, and that this one had been exposed only after Michael Brown’s death at the hands of police officer Darren Wilson put the city in the national spotlight. But it was hard to find empirical evidence about how widespread the problem really is—for all the millions of tickets that police officers in America write for low-level crimes like drinking in public, riding a bike on the sidewalk, and playing music too loudly, law enforcement agencies don’t tend to make public, or even collect, demographic data on what kinds of people are getting written up for such violations and summoned to court.

This week New York City announced plans to reform its approach to summonses, creating a system designed to make it easier for people facing fines to show up for their court dates and defend themselves. One of the most important features of the reform package, however—and one that has been discussed less than it deserves to be—is the introduction of a “race box” that will appear on every single ticket that police officers in New York write. Even more striking: The racial identity of every individual who receives a summons will be aggregated in a central database and made public, so that anyone can download it and analyze it for patterns.

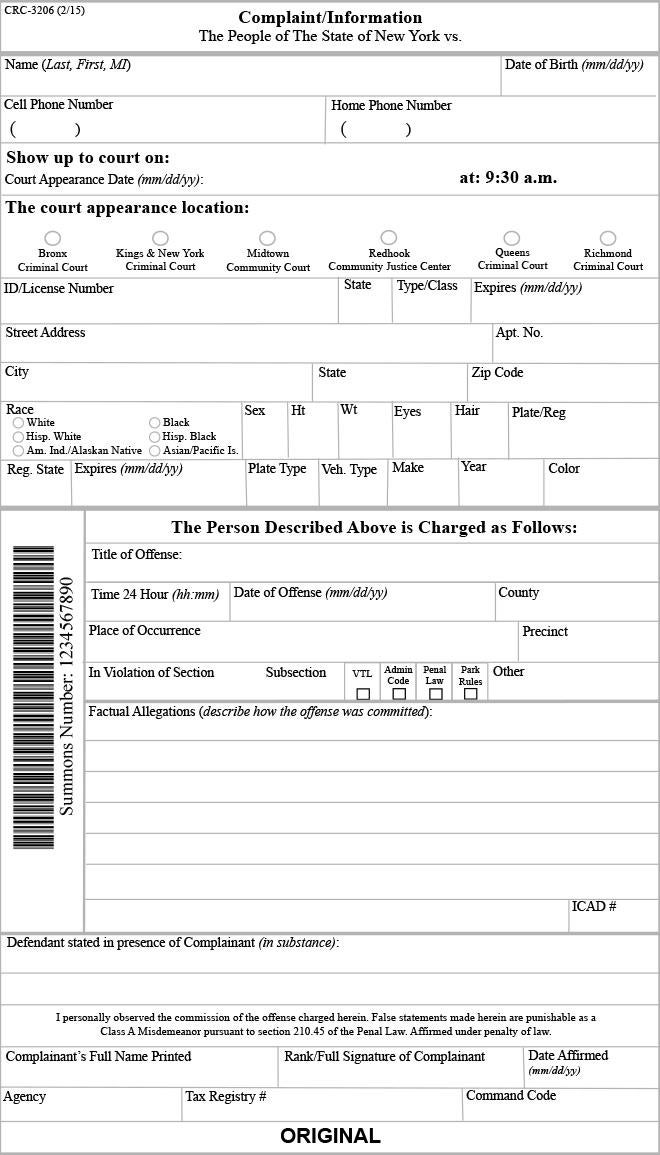

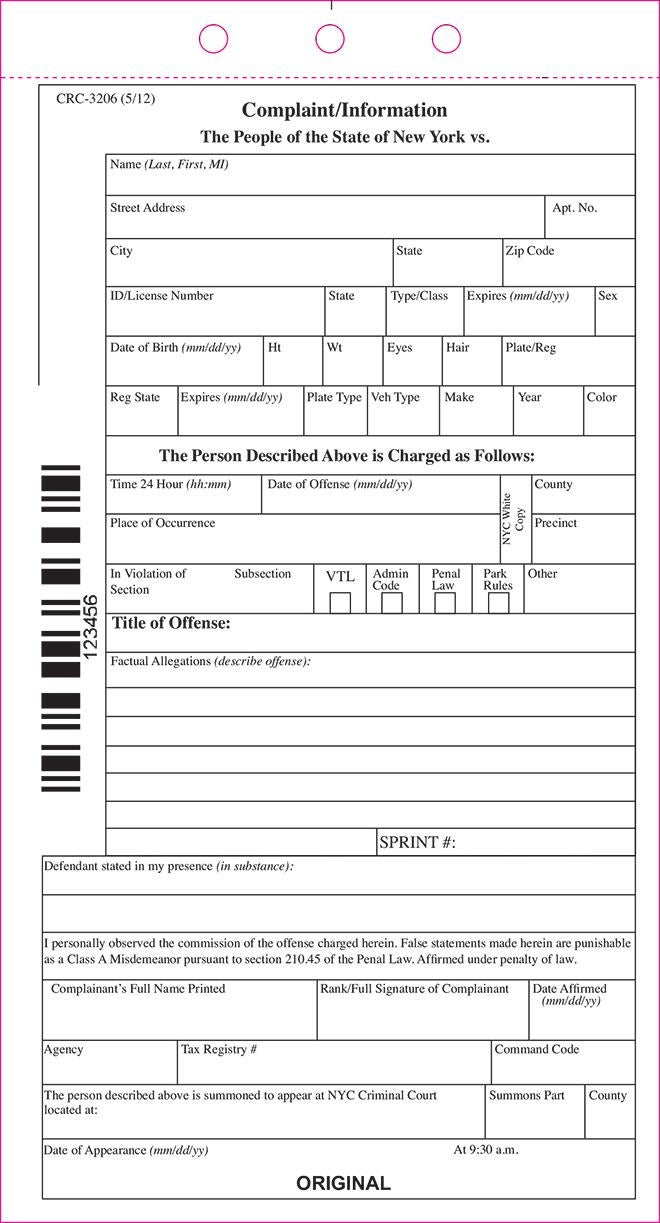

Document via NYC.gov

There may be other cities in America that do this, but I haven’t been able to find one. And according to the Mayor’s Office, at least, the new policy represents an unprecedented step toward transparency. It’s also one that reform advocates in New York suspect will definitively reveal the disproportionate burden placed on the city’s minority communities when it comes to being punished for low-level offenses. (The New York Daily News published an excellent story on this issue last summer based on analysis of where in the city people who received summonses between 2001 and 2013 were stopped.)

Document via NYC.gov

Data on racial disparities was crucial in making the case against the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk policy, which was ended largely because it was so manifestly unfair to blacks and Hispanics. With the national conversation about policing becoming increasingly focused on the cycle of debt that is created when people are stopped for low-level offenses and then punished, often with jail time, for not paying their tickets on time, having good data on who is bearing the brunt of the policies will go a long way toward demonstrating the racially skewed manner in which they are often enforced. “Poor people and people of color are … unfairly burdened by over-policing and fines,” wrote Alexandra Natapoff, a professor at Loyola Law School who studies how enforcement of rules against low-level offenses affects the poor, in an email. “New York’s new data collection requirements will help confirm this well-known fact.”

Not that that’s what motivated the implementation of the reform, which was described to me by one of its architects, Alex Crohn of the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, as nothing more than an effort to create transparency.

“You always want to know where activity is being directed,” Crohn said in a phone interview. He added, “There’s a wealth of information that folks should know about how their communities are interacting with law enforcement. It’s nothing that should be hidden or behind the curtain.”

Crohn said it was too early to tell what the data would say, and what effect it might have on policing in New York. “We’re going to have to take a look to see what comes of it, and what is to be done, if anything,” he said.

That’s a good start—and one that every city and municipality in the country should copy. If there are “other Fergusons” out there, we should make every effort to identify them, and without the Department of Justice having to get involved. And while mandating good data collection might not sound like a cure-all for the problems plaguing our criminal justice system, it has the power to expose those problems and force those in power to address them.