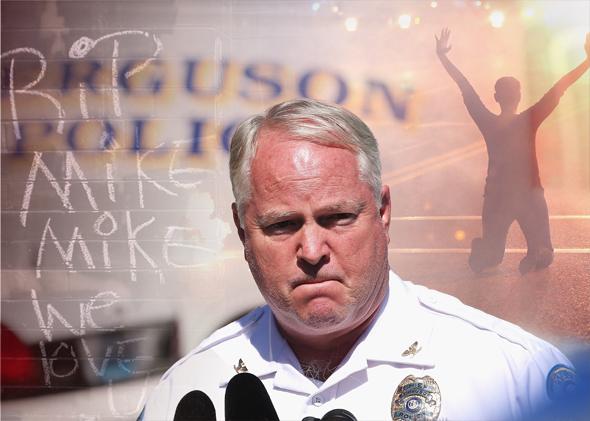

Thursday was Ferguson Police Chief Tom Jackson’s last day on the job. Jackson, who had been chief for about five years, announced his resignation earlier this month, in the wake of a report by the Department of Justice that found a culture of extreme police abuse and systematic racial discrimination taking place on his watch. He will be replaced, on an interim basis, by Lt. Col. Al Eickhoff.

It’s unlikely that Eickhoff, who joined the Ferguson Police Department as assistant chief about a week before the killing of Michael Brown, will be able to regain the trust of the city’s residents during his temporary run at the top of the organization. That work will probably fall instead to whomever the city hires to permanently replace Jackson—an undertaking that, according to a city spokesperson, will be outsourced to an executive headhunting firm that will conduct a nationwide search for candidates.

We don’t yet know which firm the city of Ferguson will be working with, or what the timeline for the search will be. But with Jackson now out of office, it’s worth reflecting on the critical importance of who will succeed him, and how that person will be chosen.

You might be wondering: Does it really matter who is in charge of this disgraced agency, if the officers who carried out its oppressive policies all still work there? The answer is yes.

“If you have a strong chief, it just counts for so much,” said Jim Chanin, a civil rights lawyer in California who was instrumental in pushing the city of Oakland to reform its police force after more than a decade of rampant brutality. Chanin’s experience has made him strongly inclined to be skeptical when law enforcement promises change: For almost a decade, starting in 2003, he watched as a consent decree imposed on Oakland law enforcement, which required the city to introduce a series of policy changes, was disregarded not only by rank-and-file officers but by their superiors as well. Then, in October 2012, Chanin managed to compel the department to start taking the consent decree seriously. (Basically, he filed a lawsuit that would have put the department under federal control; you can read the whole story of his battle with the city at Politico Magazine.) This resulted in the hiring of a new chief named Sean Whent in 2014. And that, it turned out, made all the difference: According to data cited in Politico, complaints against the police have dropped at least 40 percent over the past year. And while the years 2000 to 2012 saw an average of eight police-involved shootings per year, there were zero in 2014.

How did one new hire have this effect? “A lot of these [officers] are young people who are very impressionable,” Chanin told me. “And if they believe that the chief wants them to kick ass and take names, that’s what they’re going to do. But if the same people believe the chief wants them to follow the Constitution and treat people with respect, then they’ll do that.”

Sure, Chanin said, there are going to be some bad apples who are “beyond redemption,” and won’t change their behavior no matter what orders they’re getting. “But they’re the minority,” he said. “The majority are going to be like soldiers in the Army. And if the general says you treat people with respect and follow the Constitution, that’s what you’re going to do.”

So how will Ferguson find candidates who are capable of inspiring that kind of change? I put that question to two recruiters who specialize in law enforcement, and they described the process for me in broad strokes.

The first thing city leaders have to decide is whether they’re going to go outside the department to make the hire—something Ferguson officials haven’t committed to, according to the city spokesperson, even though in places where something traumatic and destabilizing has happened (think Los Angeles after the Rampart corruption scandal in the late 1990s) going outside of the organization is, for obvious reasons, considered preferable.

“When someone comes from the outside, they’re coming because the department sees the need for a change in direction and is looking for reform and change,” said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum in Washington, D.C.

Step two is figuring out what it is the police department needs—and what the community being served by the department wants.

“Oftentimes a town hall meeting is held where people are invited to make comments,” said Bob Murray, whose recruiting agency has carried out searches for police chiefs all over California. “The mayor and the city council might want to have a recruiter sit down and talk to representatives from the religious community, the business community, the neighborhoods.”

Once the city knows what kind of person it’s looking for—a seasoned veteran of an urban force, a reformer with experience turning around other troubled departments, a specialist in community policing the recruiting firm will place advertisements in industry publications, like the job board of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, but also newsletters from minority-oriented police groups like The National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives. The recruiter will then distribute brochures to individuals in the firm’s network who might be interested in the job. This part can be tricky if you’re trying to make a job sound appealing when, on its face, it is anything but. What do you say, exactly, to make the chief of police job in Ferguson sound like a desirable gig?

“It’s one of the challenges,” said Murray. “You have to describe those things in a positive context. If it’s a city that’s had problems, you don’t want a brochure that says, ‘Our officers are brutal and we have a corrupt department.’ ”

If those things happen to be true, though, a recruiter has to find a way to make the challenges seem attractive.

“The good news about Ferguson is, given the scrutiny and what’s occurred, everyone in the community and the leadership wants to change the situation, and they’re looking for someone to help them do that,” Murray said. “So you don’t need to say, ‘the system’s broken, you’re going to have all these problems, and it’s going to be damn hear impossible to fix them.’ You want to talk about it as a positive opportunity.”

That means appealing to people who are inclined to see a disaster like Ferguson as a chance for them to make a difference—people who can imagine being credited as turnaround artists if they succeed.

“You do have people out there who are willing to take on challenges,” said Wexler. “You just have to find them.”

It helps that law enforcement careers have been made on the strength of a rehabilitation job well done. Consider NYPD Commissioner William Bratton, who was credited with turning Los Angeles around when he joined the force there in 1992. “That’s why he’s back in New York, I suspect,” said Murray. “The track record he had in Los Angeles and the achievements he realized are notable in law enforcement history.” By the same token, he went on, “if somebody could go to a community like Ferguson … and make positive change, they’re going to gain a great reputation.”

This was the experience of William Lansdowne, who was hired as police chief of Richmond, California in 1994. He was the first chief the city hired from outside after a gang of brutal and racist Richmond officers known as the “Cowboys” were exposed on an episode of 60 Minutes in 1983. “I thought it was a chance of a lifetime to go up to Richmond,” Lansdowne told me. “It was really clear: They wanted to rebuild the organization, and … they wanted to unify the community with the police department.”

Lansdowne didn’t solve all of Richmond’s problems, but when he left the city for San Jose after five years on the job, he was credited with rebuilding relations between the police department and its minority residents through his dedication to community outreach. Eventually he became the chief of police in San Diego. His work in Richmond, he said, “opened lots and lots of doors.”

Personal ambition might not be the best quality to look for in Ferguson’s next police chief. And yet, if that ambition is matched by and a commitment to change and the skills necessary to win the trust of residents while keeping the rank-and-file motivated, a chance remains that America’s most infamous police department can be rehabilitated.