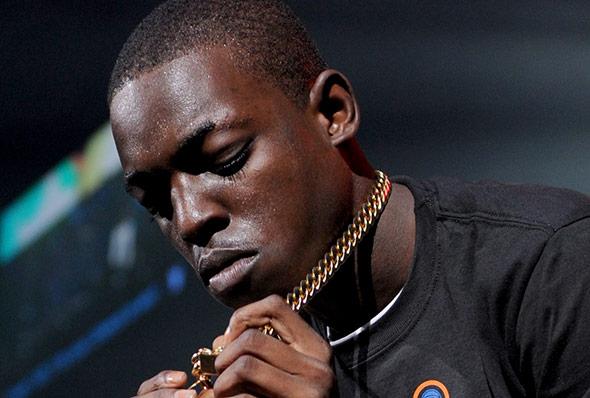

The first thing I remember reading about Bobby Shmurda was that the video for his song “Hot Nigga” made him and his friends seem like “authentically rowdy New York kids—the kind that get into fights on the train.” The line appeared in an article on Complex.com last June that presented Bobby to the world as an exciting, gritty new street rapper from East Flatbush, Brooklyn who had gained attention outside his neighborhood thanks to a six-second Vine of him dancing.

The video had the look of a home movie that was never intended for public consumption. If you were one of the 100 million people who eventually watched it, you could see the 19-year-old rapper, real name Ackquille Pollard, bounding around in the street, surrounded by dozens of young men throwing up gang signs and shooting imaginary guns at the camera with their hands. “Bitch, if it’s a problem, we gon’ gun brawl,” he rapped. “Broad daylight/ we gon’ let them things bark.” He delivered the words with a nihilistic gusto, and addressed the camera with a steely gaze that made him impossible to look away from. In July, he was signed to a seven-figure deal by Epic Records.

I thought about that “rowdy New York kids” line last Thursday as I sat in the New York State Supreme Court Building in downtown Manhattan and watched Pollard, his brother, and about a dozen of their friends get marched in front of a judge, one by one, with their arms handcuffed behind their backs. Collectively they were facing more than 100 charges, including murder in the second degree, all of them stemming from their alleged activities as a street gang, mentioned prominently in “Hot Nigga,” called GS9. At the heart of the indictment, filed by the city’s Special Narcotics Prosecutor after a year-long investigation, was an allegation of criminal conspiracy: according to the indictment, Pollard and his gang sold crack together, and made repeated attempts on the lives of rivals as part of a sustained plot to defend their territory and advance their status as an organization. The 13 young men named in the alleged conspiracy were arrested in mid-December at a recording studio in Manhattan, and they have all been in jail ever since. (It’s worth noting that, while some prosecutors around the country have lately taken to the dubious practice of using lyrics as evidence against rappers suspected of crimes, the charges against GS9 seem to be based on wiretap recordings, not songs.)

Having spent about six weeks on Rikers Island, Ackquille Pollard might be getting out on bail in the next few days. On Friday, his legal team posted a $2 million bail package that is now being examined by the district attorney’s office; if they don’t find anything to object to, Pollard will be free, and free to make music again, while his case works its way through the courts.

At first glance, the young rapper’s grim predicament—he faces up to 25 years in prison if convicted—looks like a singular story about a star whose meteoric rise was outstripped only by the swiftness of his downfall. But Pollard’s defense attorney, Ken Montgomery, sees it very differently.

Montgomery is 42 years old. He is black and grew up in Brownsville, a neighborhood that borders East Flatbush and which saw more shootings last year than all of Manhattan. Montgomery is neither shy nor apologetic about his distrust of law enforcement and prosecutors. His clients have included the families of Akai Gurley and Kimani Gray, both of whom were killed by NYPD officers in cases that sparked public protest, and the rapper Maino, whose anti-police song “Hands Up” recently made headlines when it was reported that lawyers from the Bronx Defenders had appeared in its music video.

In an interview last week, Montgomery played down his new client’s celebrity status, and made a point of describing him instead as utterly typical: one of the countless young black men around the country who have been systematically denied opportunity and who find themselves in the crosshairs of a criminal justice system eager to put them behind bars. “There’s a bunch of Bobby Shmurdas out here,” Montgomery told me. “This is part of a bigger thing.”

The “bigger thing” Montgomery is talking about is the world Ackquille Pollard was born into, a world in which “gangs” are not the sophisticated, hierarchical organizations that come to mind when you hear the word conspiracy, but rather groups of teenagers who became friends with each other as a result of living on the same block, and intuitively band together in order to protect themselves. Reading the prosecutor’s indictment against Pollard and GS9, you get the impression that the crew was living under constant threat of attack from enemies whose reasons for wanting to hurt them were based on little more than geography. Though the members of GS9 were armed to the teeth—police recovered a truly alarming arsenal of illegally obtained guns—the battles they fought on the streets of Brooklyn appear, at least from the outside, to have been instigated by tragically petty slights, like a rival gang member driving his car down the wrong street. Like so many other small gangs—in New York, in Boston, in Chicago—GS9 seems to have been locked in a cycle of retaliation so longstanding that its origins had become irrelevant.

As Eric Konigsberg reported in an article for New York, published a few weeks before “Hot Nigga” started playing out of car stereos all over the city, “schoolyard gangs” in places like Brownsville and East Flatbush “aren’t cut from the same mold as the drug-dealing enterprises of just a decade ago.” Rather, they’re “cliques of middle- and high-schoolers, divided by block or housing development, who, unlike their forebears, don’t see what they’re doing as a ticket to someplace better.” Konigsberg quotes Marc Fliedner, an assistant district attorney in Brooklyn, explaining how strange it was for him and his colleagues to realize that the “gangs” they were trying to take down weren’t even necessarily trying to make money. “It’s just territorial nonsense,” Fliedner said. “‘You’re from another building, so I hate you.’ ”

Neighborhoods haunted by such high-stakes nonsense exist all over the country, Montgomery told me, and the violence in these places is so unrelenting that the kids who live there lose faith in the idea that a better, or even different, life is possible. Consequently, they make what they believe is the best of it, meaning they acquire weapons for self-defense, and maybe start selling drugs to earn money. “It’s either predator or prey in those neighborhoods,” Montgomery said, pointing out a scar across his chin that he got in a fight at age 15. “These kids are under siege from the cops and they’re under siege from each other. And that little territory that they have—that is the small space where they can operate. They’re powerless everywhere else, but within those confines they can find … what they perceive to be power.”

Montgomery argues that this is what happened to Ackquille Pollard and his friends, which is why he thinks their prosecution should be seen not as tabloid fodder but as a social justice issue—one that has particular relevance at a time when the Black Lives Matter movement, inspired by the death of Eric Garner and Michael Brown at the hands of white police officers, has fueled a national conversation about the racism lurking in America’s criminal justice system. Young men like Pollard, Montgomery said, are deprived of the resources that could put them on a productive path in life—good schools, adult role models, jobs—then thrown in prison when they turn to crime to get by. Montgomery wants the young hip-hop fans who identify with the world they saw in Bobby Shmurda’s “Hot Nigga” video, and helped make the song a runaway hit, to see Pollard’s arrest and prosecution as a cautionary tale. The system, he says “has a place for you. And it’s not a place where you want to be.”

The question is whether the world will accept Bobby Shmurda as a symbol of injustice—and whether it should. Does a guy whose stage name contains a reference to murder, and who brags in his hit song about shooting another person and watching his body “twirl” before falling to the ground belong in the same conversation as victims of lethal police violence like Akai Gurley, Eric Garner, and Michael Brown?

I posed the question to Paul Butler, a professor at Georgetown Law and the author of the book Let’s Get Free: A Hip-Hop Theory of Justice. Butler was not familiar with the Bobby Shmurda case before I told him about it, but he quickly put it into context in a way that made it clear, to me at least, that principled activism undertaken in the name of the public good sometimes requires lining up behind a figure who is unlikely to elicit empathy from large swaths of society.

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, Butler said, during the early days of the civil rights movement, activists pursued a strategy known as the “politics of respectability.” The idea was to illustrate the realities of systemic discrimination for policymakers and voters by showing them how it affected a few carefully chosen, perfectly sympathetic, and morally unassailable individuals. This is where we got Rosa Parks, Butler said. Though she wasn’t the first woman to refuse to give up her seat at the front of a bus, she was the most likely to win the hearts and minds of the public, and so the cause came to rest on her shoulders.

“If we think about the first phase of the civil rights movement, when activists were attacking Jim Crow and the segregated lunch counters … the leaders looked for people who were blameless victims, and they made them symbols of the movement,” Butler said. Overall, he added, “it was a fabulous success story.”

The problem for modern criminal justice reformers, Butler said—especially those focused on how the system treats violent offenders—is that the politics of respectability are nearly impossible to harness when the people you’re trying to help look less like victims and more like perpetrators. When it comes to addressing the systemic forces that cause young black kids from poor neighborhoods to join gangs, there just aren’t many “perfect victims” to choose from: almost by definition, the people most crippled by the circumstances you hope to call attention to are people who have been turned into villains. Figuring out how to overcome this problem, Butler said, represents the next phase of criminal justice reform, which so far has been focused on making the system less punitive toward nonviolent drug offenders. Now activists must “extend the critique of mass incarceration and race disparities from the war on drugs to other crimes,” and that extension, Butler said, is exactly what he sees going on in the case of Ackquille Pollard.

Listening to Ken Montgomery lay out the case for Pollard as a symbol of all the ways that American society fails its young black men, it’s tempting to dismiss his argument as little more than spin—the work of a shrewd defense lawyer doing whatever he can to make his client seem less responsible for his alleged crimes, even if that means linking him to an important social justice movement that could conceivably lose credibility by being associated with the guy from the “Hot Nigga” video. In an email, a spokeswoman for the Special Narcotics Prosecutor’s office described the case against Pollard and GS9: “This gang was involved in a murder and numerous shootings, as well as other crimes. Several shootings involved indiscriminate gunfire, including one in which an innocent bystander was seriously injured.” You don’t even have to be skeptical of Montgomery’s sincerity to think that Pollard and his friends aren’t worth defending in the same terms as Michael Brown or Eric Garner.

And yet: if reform-minded activists really do believe that growing up in places like East Flatbush and Brownsville—where, as Paul Butler put it, “structural deprivations and wretched conditions” make it much more likely that a child will get involved in drugs, gangs, and guns—then who exactly are they waiting for?

About a week ago, the professor and MSNBC host Melissa Harris-Perry devoted a few minutes of her program to respond to a tweet by New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof. In the tweet, Kristof had suggested that, in light of Michael Brown’s alleged involvement in a convenience store robbery minutes before his death, activists in the Black Lives Matter movement perhaps should have focused less on him and more on the shooting of 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland. The implication was that Tamir Race would have made a better mascot: As a perfect innocent he left less room for skeptics to debate whether he might have somehow provoked the use of lethal force against him. Kristof’s point was a perfect example of the politics of respectability. But Harris-Perry wasn’t having it.

“Just wanted to say thanks for the strategic advice you offered Friday afternoon,” she said sarcastically. “It was a great reminder of how important it is to endure injustice until just the right victim comes along.” Her point was that it didn’t matter whether Michael Brown did or didn’t rob a convenience store, or whether Tamir Rice had been a “more perfect victim, a more palatable protagonist to dramatize the fragility of black lives.” The point of the Black Lives Matter movement, she concluded, is that “all black lives matter,” not just the ones belonging to individuals who are easy to put on a pedestal.

Bobby Shmurda is not a perfect victim. Given that he may well be the perpetrator of numerous violent crimes, and is someone who has rapped with unrestrained glee about murdering his enemies, he is not even close. But if you believe young men like him need help, not just punishment, you might need to stand with him as he faces his charges, even if those charges, and his image, make it politically difficult.

That doesn’t mean arguing that Pollard should go free if he’s found guilty of his alleged crimes—far from it. It means recognizing that he can’t escape the consequences of his actions—that our society requires him to answer for the life he’s lived, whether he’s a victim of circumstances or not. To look at Pollard’s case through this lens is to confront the urgent need to improve the neighborhoods in which kids like him are forced to grow up. Those of us who thrilled at the authenticity we heard in his music, who felt a vicarious charge from the claustrophobic, violent street life depicted in the “Hot Nigga” video, owe him at least that much.