Before Eric Garner couldn’t breathe, William Cardenas couldn’t breathe. It was 2006, and Cardenas, a 23-year-old Los Angeles resident, was drinking a beer on a sidewalk when two LAPD officers approached. Cardenas had an outstanding warrant for his arrest. He ran. The officers pursued, apprehended, and subdued him. The official police report noted that one of the officers struck Cardenas twice in the face after he resisted arrest.

The truth was somewhat different. A video of the encounter that surfaced after Cardenas’ arrest showed one officer punching Cardenas in the face five times while he lay on the ground, one wrist already handcuffed. Both officers sat on top of Cardenas, one pressing his knee against his neck, the other straddling Cardenas’ abdomen. “I can’t breathe,” Cardenas said repeatedly. “I can’t breathe.”

Before William Cardenas couldn’t breathe, Anthony Baez couldn’t breathe. He didn’t say so, but it’s hard to draw any other conclusion. In December 1994, Baez, a 29-year-old security guard, was playing football with his brothers in the Bronx when an overthrown ball struck a parked police car. New York City Police Department officer Francis Livoti responded by grabbing Baez and putting him in a chokehold; Baez, an asthmatic, choked to death.

What do Baez, Cardenas, and Garner have in common? William Bratton.

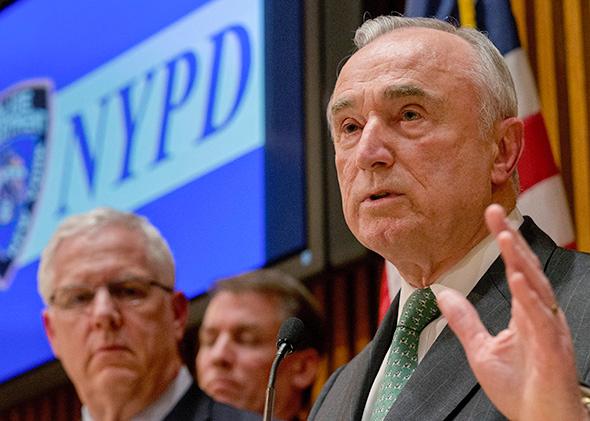

Bratton, the current commissioner of the New York City Police Department, was Los Angeles’ police commissioner when Cardenas was deprived of breath, and NYPD’s chief during the Baez incident. Bratton is the nation’s leading proponent of broken windows policing, which encourages cops to doggedly maintain order in dangerous neighborhoods, ostensibly as a way of stemming violent crime before it starts.

Critics of broken windows—I am one of them—have argued that while there is no evidence that the approach is effective in lowering the violent crime rate, there is plenty showing that it encourages cops to engage in the sort of overly aggressive policing that promotes community fear and mistrust of law enforcement, leads to increased brutality complaints from civilians, and, occasionally, ends up with cops unnecessarily killing people who are unarmed.

The defenders of broken windows disagree. They say the theory is sound; it’s just that it isn’t always competently applied. In December, after a grand jury declined to file charges against an NYPD officer accused of killing unarmed Staten Island man Eric Garner with a chokehold the department forbids, Bratton told the media that New York police would be retrained and would learn better techniques to ensure both their safety and the community’s.

We’ve heard that before. From New York to Los Angeles to New York again, William Bratton’s career has been pockmarked by “I can’t breathe”–grade incidents, by increased civilian complaints of excessive force. And every time, more or less, Bratton has responded by calling for training reforms and resisting outside intervention into police disciplinary methods. Police brutality and excessive force are problems in all police departments, not just Bratton’s. But Bratton’s reputation as a reformer, as well as his history of evading responsibility for excesses committed by officers under his command, merit more scrutiny than they’ve received.

Bratton is the most celebrated police official of his era. At every stop in his managerial career, he has modernized police departments, improved community relations, boosted officer morale, and reduced crime rates. But at every stop, community complaints have risen and officers have become less accountable to the communities they serve. This is in part because of Bratton’s adherence to broken windows, which requires officers to aggressively enforce quality-of-life violations. Doing this well requires better training. But Bratton’s career has been characterized by training breakdowns, and an ostensible inability to communicate with his officers.

For example: In the spring of 1994, NYPD officers chased and killed an unarmed Staten Island man named Ernest Sayon. A New York Times article noted that witnesses described “a suspect in restraint who mostly lay still as officers beat him, put him in a choke hold and kneed him in the back”; witnesses also recalled the police “picking up and frisking people seemingly indiscriminately” before Sayon caught their attention. The city medical examiner called Sayon’s death a homicide and concluded that Sayon died of asphyxiation due to chest and neck compression. A forensic pathologist hired by Sayon’s family later found evidence that Sayon had been put in a chokehold.

In response to the protests, Bratton suggested the real problem was undertrained police who, ever since the chokehold was banned in 1993, lacked adequate strategies for subduing unruly arrestees. As Regina Lawrence put it in The Politics of Force: Media and the Construction of Police Brutality, Bratton framed the problem “as one of resistance-prone subjects, not violence-prone officers.”

Weeks after a Staten Island grand jury declined to pursue charges against the officers who killed Sayon, Baez was killed in the Bronx. Baez’s death highlighted a spate of abuse complaints in the borough. A New York Times investigation noted that, according to senior police sources, abuse complaints in the Bronx had “spun out of control” in the year after Bratton took office. An aide to Bratton told the Times that “commands sent from Police Headquarters to the Bronx precincts for the police somehow got distorted” in transit.

In 2002, Bratton moved west to take over the Los Angeles Police Department. As always, the crime rate dropped when he was there. As always, brutality complaints increased. “The new chief demanded patrol officers replace their smile-and-wave style with aggressive policing,” the Los Angeles Times wrote in 2004, after three police officers came under investigation for excessive force after chasing an unarmed car-theft suspect and beating him with a flashlight while he was under restraint. “Bratton says all the right things about improving relations between the police and the African American community,” a local civic leader said in a Los Angeles Times op-ed in 2005. “But there is a major disconnect between his vision for the LAPD and that of his officers at the street level in South Los Angeles.”

The notion that overaggressive officers are somehow misinterpreting Bratton’s orders has been a common refrain throughout Bratton’s career. And yet the one thing that Bratton’s supporters and detractors agree on is that he is a fantastic manager and communicator, someone who cuts through bureaucracy and inspires loyalty in his officers.

One way to garner the support of your underlings is to shield them from external criticism. And Bratton has a record of resisting transparency in his police departments. Overzealous civilian oversight or the threat of being held accountable for their actions causes cops to be tentative, which makes them less effective at maintaining order. Throughout his managerial career, Bratton has consistently advocated for policies that give police officers latitude to enforce the law free from outside scrutiny and discipline.

Bratton took office in New York right after the independent Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) had been granted new power to investigate and recommend discipline for officers accused of misconduct. (Before that, he had led the Boston Police Department for about six months.) But the head of the CCRB, Hector Soto, resigned in late 1995, weeks after his agency issued a report “showing a 31.8 percent increase in brutality complaints against New York City police officers in the first six months of [1995],” as the New York Times put it. The Daily News noted that Soto had “repeatedly irked Police Commissioner William Bratton with the aggressive manner in which his staff sought out citizen complaints and with periodic reports that showed a skyrocketing number of police abuse complaints throughout the city.”

In January 1995, Bratton fired Walter S. Mack, Jr., head of the NYPD’s Internal Affairs Division, for what was officially deemed poor communication on Mack’s part. Mack publicly denounced the move as retaliation for his independence and vigor in investigating NYPD corruption and urging charges against offenders. “I have been accused of not being a team player when I felt the department was not best served by tolerating perjury and misconduct that I believed was criminal,” Mack told the New York Times. After Mack left, Internal Affairs shifted its focus to conducting sting operations and arresting officers for off-duty offenses. Several anonymous police officials told the Times that “the department was reluctant to push hard on corruption because of concerns for its reputation.”

When Bratton came to the LAPD in 2002, he replaced Bernard Parks, who was astoundingly unpopular among his officers for his disciplinary policies. Parks had a track record of documenting and investigating every single civilian complaint that was lodged against his officers. Parks ended up firing more than 130 officers during his tenure, and morale plummeted among the remaining ones, who despised what they saw as Parks’ overly punitive leadership style.

Bratton went in the opposite direction, presenting himself as a chief who, first and foremost, had his officers’ backs. “The game of ‘gotcha’ in this department is coming to an end,” Bratton told his officers in 2003, and he meant it. In 2005, complaints against LAPD personnel rose, while the rate of suspensions and firings fell by 46 percent from the previous year. In 2008, Bratton asked for and received a change in the department’s disciplinary rules to allow him to circumvent regulations and discipline officers without the need for a formal disciplinary review.

So now Bratton is back at the helm of the NYPD. When he got there last year, just like he did in Los Angeles, he blamed his predecessor, Ray Kelly, for the department’s awful morale, and promised he’d make changes. The community, too, is demanding change at the NYPD. But if history is any indication, the sorts of changes Bratton wants to make are not at all the same as the ones the public wants to see. The public wants an NYPD in which officers who are too aggressive are made to answer for their actions, where cops don’t feel implicitly encouraged to cross the line between order maintenance and repression. There is nothing in his managerial history to suggest that Bratton is the man to deliver these reforms.

Bratton’s broken windows policy encourages cops to police aggressively, while his preference for opaque and insular disciplinary policies tells cops they are primarily accountable to Bratton instead of the communities they serve. You can’t fix broken windows abuses unless you’ve got a commissioner willing to crack down on overaggressive policing. But you can’t effectively deploy broken windows unless you tacitly encourage cops to be overaggressive. And that’s the problem. More than 20 years into the broken windows experiment, it’s obvious that improved training won’t fix the abuses the philosophy engenders. Overaggression in broken windows policing isn’t anomalous—it’s normative behavior.

Bratton surely knows this, and anyone who’s been paying attention must know it, too.