This article is adapted from “The Trials of White Boy Rick,” the newest single from the Atavist. You can purchase the full story from the Atavist’s website. It is also available on Amazon.

Late on the morning of May 21, 1991, a small turboprop airplane descended into Detroit City Airport. Outside the perimeter fence of the small airfield on the city’s east side stood an auto repair shop, some forlorn houses, a shady motel.

The plane taxied to a remote corner of the tarmac, and a Lincoln Town Car pulled up nearby. Three men stepped down from the plane. Another man got out of the car to meet them. They shook hands, then got to work lugging a series of black duffel bags from the plane to the trunk of the Town Car. The bags contained 100 kilos of white powder.

The man in the Lincoln was named Jimmy Harris. He was a sergeant in the Detroit Police Department. And he was heading up a group of police who had agreed to provide an escort for a shipment of cocaine. As an extra precaution, he had given a secure police radio to his business partners in the plane so they could follow the movements of any cops who weren’t in on the deal—who were, in other words, clean.

The Lincoln pulled out of the airport and headed southwest beyond the city to the suburbs. Several police vehicles, including marked cruisers, followed close behind and saw to it that the cargo safely reached its buyers. Later that day Harris arrived at a hotel room in the Detroit suburb of Dearborn to meet with the drug trafficker who had hired him. He had Harris’ payment ready: $50,000 in cash for the cops’ services.

Unbeknownst to Harris, however, a special agent of the FBI, Herman Groman, was listening to the conversation on his headphones from the adjacent room. He had been working with a team of about 100 people to prepare this sting down to the last detail: the plane full of FBI agents disguised as drug smugglers. The buyers—also FBI—waiting to receive the goods. The cocaine in the duffel bags—a kilo of the real stuff on top, in case a wary cop asked for a taste, and 99 more of flour. Hidden cameras and microphones had recorded everything that transpired on the tarmac. A surveillance aircraft had even tailed Harris’ car. Now a special camera with microwave technology was pressed against the wall, and it showed Groman’s team a moving image of what was happening in the next room in real time.

Over a period of months, Harris and his associates had taken payoffs to supply police protection for five deliveries of suitcases filled with $1 million in drug money to be laundered in Detroit—in reality, cut-up paper with a few layers of genuine bills on top. And now he was completing the deal on the second of two large shipments of purported cocaine. Harris knew the man who was paying him off as Mike Diaz, a heavy hitter from the Caribbean, but he too, of course, was actually an FBI agent, real name Mike Castro.

After he gave Harris the money, Castro convinced him to stay for a celebratory drink and excused himself to get some ice from the machine in the hall. A minute later there was a knock at the door. Harris opened it and was greeted by a SWAT team.

The sting, which the FBI had dubbed Operation Backbone, netted 11 police officers and several civilians. It was probably the most extensive probe of police corruption ever undertaken in Michigan, Groman says, and the bust made national news.

It was clear to everyone that the FBI must have had help. Someone credible had to have convinced Harris and his partners that they could trust “Mike Diaz,” a stranger looking to enlist them in a major illegal plot. Federal agents rely heavily on informants and criminals who decide to cooperate, particularly when the suspects being targeted are savvy people who understand how investigations work—such as big-city cops. The name of the man who set Operation Backbone in motion was a serious surprise in Detroit. And his saga, which has never fully been told before, shines a light on what happens to informants after their identity has been revealed—especially when they’ve implicated powerful officials.

* * *

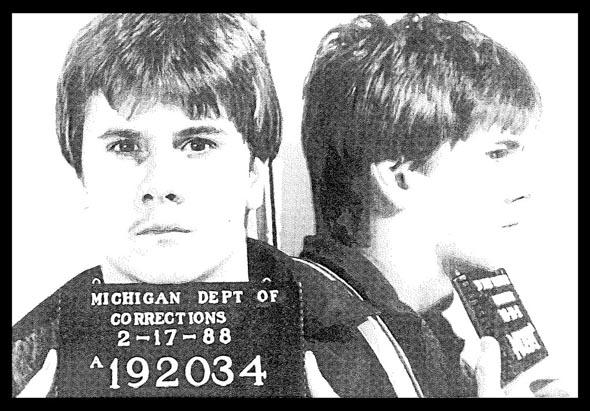

That man was Richard Wershe Jr., a legendary criminal figure in Detroit and an enduring symbol of the height of the cocaine era. Before he was imprisoned in 1988, two years before Operation Backbone began, Wershe drove a white Jeep with the words THE SNOWMAN emblazoned on the rear, though he had no driver’s license. He wore tracksuits and chains, mink coats, a belt made of gold, a Rolex encircled with diamonds. But the source of his novelty was simpler, and it was immediately apparent in the mugshot taken after the arrest that ended his career: The person in the picture was barely capable of growing a mustache, with baby fat still filling out his cheeks. He was 17 years old. And he was white. According to an east side kingpin I spoke to, Wershe “was the only white boy that ever sold dope in the neighborhood at that time.” To this day, most of Detroit knows Wershe only by his nickname: They call him White Boy Rick. In “Back From the Dead,” Detroit native son Kid Rock rapped, “One bad bitch, I smoke hash from a stick/ Got more cash than fuckin’ White Boy Rick.”

I first learned of Wershe’s story last year and quickly became fascinated. I spoke to a number of police officers and federal agents who had figured in the case in one way or another. With some surprise, I discovered that while most of them remembered the story in detail, few of them had any idea what had happened to Wershe since the Reagan administration. It was as if the legend of White Boy Rick had swallowed the real person at its center.

In fact, Wershe was more or less where people had last seen him in the late 1980s: sitting in a prison cell in Michigan. This made Wershe not only a local icon but also an anomaly, and something of a mystery, in the world of criminal justice. In May 1987, when he was 17, Wershe was charged with possession with intent to deliver 8 kilos of cocaine, which police had found stashed near his house following a traffic stop. He was convicted and sentenced under one of the harshest drug statutes ever conceived in the United States, Michigan’s so-called 650 Lifer law, a 1978 act that mandated an automatic prison term of life without parole for the possession of 650 grams or more of cocaine. (The average time served for murder in state prisons in the 1980s was less than 10 years.) The governor who signed it into law has called it the worst mistake of his career, and the statute has since been rolled back, opening the door for a wave of convicts to be released. Wershe is the only person sentenced under the old law who is still in prison for a crime committed as a juvenile.

Police photo of Richard Wershe Jr., 1988.

Courtesy of the Michigan Department of Corrections

The question was why. After all, Wershe had by all accounts been essential to the success of Operation Backbone. At Groman’s request, he had introduced Castro to an ex-girlfriend of his, Cathy Volsan, portraying him as a big-time dealer. Volsan was well-connected with Detroit police in suspicious ways—she bit the hook, and the sting was underway. Wershe not only kept the phony story going with Volsan but continued to vouch for Castro to others involved in the protection scheme. “The undercover agent’s very life,” Groman later testified, “at times rested solely in the hands of Mr. Wershe.” Mike Castro told me, “Without him, the case wouldn’t have happened.”

And yet, for all the help he provided, Rick Wershe is still behind bars, while offenders convicted of more serious crimes have long since been freed. Was he there in spite of the assistance he had given to federal agents—or because of it?

* * *

From the beginning, Wershe was one of the most confounding figures in the history of Detroit crime. Starting at age 14, he somehow managed to ingratiate himself into the entourage of Johnny “Little Man” Curry, one of the most prominent drug lords in his neighborhood on Detroit’s collapsing east side. At 17, he bypassed Curry—who was now in jail—and began importing cocaine from major Miami suppliers himself. He also took up with Curry’s wife. Nobody quite knew how he had managed to pull all this off—and then after his arrest, the story got even stranger.

Just after Wershe’s trial, his father, Rick Wershe Sr., agreed to several interviews with reporters. To each one, he told a story that sounded unbelievable. Both he and his son, he said, had worked as informants for the FBI for years, since long before Rick Jr. landed in legal trouble.

“They used me,” he said, “and they used my son.” The Wershes had put themselves at great risk, he claimed, to help authorities gather important evidence of drug dealing on the east side. “And now they turn around and fuck us over,” he told Detroit Monthly.

It was a baffling assertion, coming at a strange time. If it were true that White Boy Rick had been working with the FBI all along, why hadn’t his lawyers mentioned it in the trial? Rick Sr. was not the most credible figure—he was facing his own criminal charges, for possessing illegal silencers found in a raid and for threatening an officer outside the courtroom during his son’s trial. The FBI told reporters that, per agency policy, they would neither confirm nor deny any relationship with the Wershes. An assistant U.S. attorney said he very much doubted the father’s claim. “I would have been told,” he said, speaking to the Detroit News. Even Wershe’s lawyer threw water on the story. “No way” was Wershe helping the feds, he told Detroit Monthly. “Maybe his dad, OK. But not the son.”

But Wershe himself has continued to insist over the years that he was a valuable teenage informant who fed the authorities intelligence on high-profile criminals. He claimed that one of the FBI agents who had handled him as an informant was a man named James Dixon. When a reporter asked Dixon about this notion not long after the trial, he refused to comment on the subject, though he did say that any suggestion that the law had betrayed Wershe was “ridiculous.” Dixon resigned the same year and never said another word publicly about the case.

Today, Dixon lives in a Detroit suburb and fishes in tournaments. When I called him recently, he spoke tentatively at first and asked repeatedly about me and what I was writing. He seemed more at ease after I told him that I had spoken with several colleagues of his from the time. We began by discussing a major east side drug gang that Wershe claimed to have helped bring down beginning at age 14. Dixon mentioned in passing “an informant” he had worked with, without giving a name.

“Was that informant Richard Wershe?” I asked.

There was a long pause. “Yes,” Dixon said.

Over the past year of speaking to Wershe and to federal investigators, police, defense attorneys, and prosecutors, former Detroit kingpins, and others—and reading a cache of FBI documents—I have been surprised to discover just how much of what Wershe has claimed about his case is true. Before he was old enough to drive, Wershe was instrumental in bringing down some of Detroit’s most notorious drug figures.

But ratting on cocaine dealers was one thing, and implicating public officials quite another. Decades later, Wershe is left wondering if he should never have spoken out.