Update, March 12, 2013: After deliberating for 16 hours, the jury found Gilberto Valle guilty of both conspiracy to kidnap several women and unauthorized access of a government database. He will be sentenced on June 19.

NEW YORK CITY—One day last summer, New York City police officer and accused cannibal-sex plotter Gilberto Valle typed this phrase into Google: sound you make with the knife before carving.

“That is not normal,” assistant U.S. attorney Randall Jackson tells a packed courtroom Thursday, as this troubling two-week trial draws to a close. In the government’s version of the facts, Valle had been working up “practical and strategic” plans to kidnap, rape, torture, kill, and eat several women, including his own wife. This Google search shows he was looking for audio clips of knives being sharpened, utensils clanking, or whatever else might serve to whet his violent appetite. “Officer Valle is a sexually sadistic individual,” Jackson concludes. “This is a man who is sick.”

But if Valle suffers from a mental illness, no one talks about a treatment. On Thursday, the jury in the Cannibal Cop case began its deliberations. If they choose to convict, the 28-year-old father may spend the rest of his life in prison. In the view of Jackson and his fellow prosecutor Hadassah Waxman, this would make the world a safer place. “That the women were not actually kidnapped is incredibly fortunate,” said Waxman in the opening of the government’s summation. The defendant never touched his victims, nor did he ever buy the large cooking tray, the largest cooking tray, the huge cooking tray, or the smoker grill for which he’d also searched online. He never squirreled away a coil of rope or jar of chloroform, as he said he’d do in online chats. He never built a pulley apparatus in his basement, or bought a cabin in the mountains, as he’d also claimed to his alleged co-conspirators. Yet the government saw him as a serial killer in waiting.

The fact of Valle’s failure as a kidnapper and a flesh-eater has no bearing on his guilt, of course. Some laws exist to prevent crimes before they happen, Jackson explains. As an example, he cites DUI arrests: Even if a drunken driver doesn’t end up in an accident, he puts everyone on the road at risk. The jury is left to probe the limits of this analogy—is Valle really like an inebriated motorist? A driver on the highway can be tested with a Breathalyzer: If he’s above a certain threshold, then he’s deemed a menace. But what about the sexual sadist whose mind is full of fantasy? How do you decide when those thoughts have gone too far?

That’s what makes this case so confusing and upsetting. If Valle really planned to kill his wife and friends, then he’s guilty of an enormous crime. But if he didn’t plan to kill them—if this was just intense role-playing, as his lawyers have alleged—then he is completely innocent. There’s no hazy middle ground, no legal space in which a drunken driver, for example, might be a little buzzed but not so blitzed that he’s declared a danger to society. But Gilberto Valle must be one thing or the other. He’s a monster or a martyr. There is no in-between.

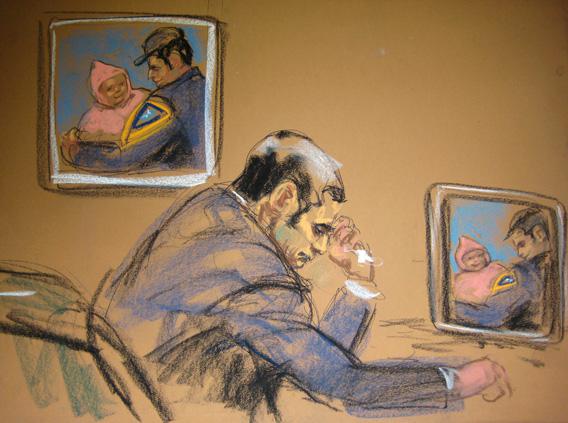

The defendant shows up Thursday morning in his dark-gray suit. Right before he sits he takes a breath, puffing out his cherubic cheeks in a deep exhale. On Wednesday afternoon, as his lawyers wrapped up their modest case, Valle pinched his nose and wiped away a tear. Now his lawyer, Julia Gatto, tells the jury that his life is ruined. “He’s lost everything,” she says, and shows a photo of the officer in his uniform, holding up the baby girl that Valle’s wife has whisked away to Reno, Nev. Valle begins to cry.

Gatto’s closing claims that Valle is a decent guy who has indecent thoughts. The problem is the mooks in law enforcement who aren’t hip to S&M. Valle’s online life is nasty, she concedes. We’ve seen his porn in open court—the ultimate embarrassment for any modern man—and Valle’s stash is pretty gnarly: He’s looked at autopsy photos of women slashed and shot; scenes of people roasting on a spit; a video of a girl who’s chained at hand and foot, with a tattoo and belly-button stud, crying out as a candle-flame effect pretends to burn her crotch. “It’s gross, no dispute,” says Gatto, but “the government simply doesn’t understand what fantasy role-play is.”

She singles out FBI special agent Corey Walsh for this attack, all but calling him a square. He’s the one who went through Valle’s hard drive and testified last week. “[Walsh] didn’t understand that stories come in different forms,” Gatto says. When the agent uncovered Valle’s online chats, detailing gruesome plans to rape and kill, he split the records into piles. According to his G-man logic, 21 of 24 were fake. Though the acts described therein were violent and illegal, Valle made it clear he wasn’t serious. He negotiated prices for a kidnapping, and described how he would use chloroform and rope to carry out the crime. He posted photos of his wife and friends, and offered them for sale. But he also gave disclaimers: “No matter what I say, it’s make-believe,” Valle wrote to one fetish friend. “I just have a world in my mind,” he told another, “and in that world I am kidnapping women and selling them.”

But the remaining chats—three of them—didn’t have those all-important caveats. At one point Valle’s partner asked him, “ARE YOU REALLY RAELLY [sic] INTO IT?” Valle typed that he was. “I am just afraid of getting caught,” he said. He’d kill and eat a girl if he could.

The government cites these back-and-forths as evidence that Valle meant to carry out his plans. Gatto says that fantasists are prone to fantasizing that their fantasies are real. It’s like “dark improv theater,” she explains: If someone asks you, “Are you for real?” then you have to say “yes” or the scene is over. Valle didn’t pause to disavow his plans in these three chats, but that doesn’t prove they’re real. Over and over again in her summation, Gatto reminds the jury that “80 percent” of Valle’s chats were designated as “fantasy.” It’s a funny piece of rhetoric, since it makes it sound as though the rest might be genuine. Also, it’s inaccurate: Agent Walsh assigned 21 of 24 to the fantasy pile—88 percent.

Jackson, the prosecutor, smacks down Gatto’s two-piles defense. It’s not surprising, he contends, that a real-life cannibalistic killer would indulge in fantasies about cannibalistic killing. “Cops watch cop movies,” he says, “and soldiers play Call of Duty.” This sounds sensible, until you remember that cannibalistic killers aren’t quite as common as cops and soldiers. All throughout the trial, the government has had to argue that Valle’s weird, cartoonish thoughts were plans for real-world action, no matter how improbable they sound. If Valle said he’d like to roast a girl on an outdoor spit with an apple in her mouth, then that’s what he was going to do.

Some of the most damning evidence against the defendant was also the most absurd. At one point, the defense convinced the judge to exclude a portion of a chat transcript in which an online friend claimed to have purchased delicious babies from drug addicts desperate for a fix. The judge agreed that this statement, made by someone other than the defendant, might so horrify the jury that Valle would himself be blamed. But couldn’t this have gone the other way? Maybe the baby-eating detail would have convinced the jury that this was nothing more than silly make-believe for cybersex.

Search terms from the defendant’s browser history might have had the same effect. When Valle entered I want to sell a girl slave into Google, was he really looking for a buyer, or had he simply given voice to thoughts inside his head? (Later on, his wife put the phrase my husband doesn’t love me into the same computer, another case of typing-what-you’re-thinking.) Valle also looked up cases of real-life abductor-murderers, and spent some time on the Huffington Post, reading an article titled “Cannibalism Can Be Addictive, Expert Says.” And in the strangest twist of the fantasy/reality conundrum, the prosecution presented evidence that Valle had searched the phrases how to abduct a girl and how to chloroform a girl on the Internet, and that he’d also viewed a 2009 blog post on Techdirt called “If You’re Kidnapping Someone, Maybe Don’t Search Google For ‘Kidnapping.’ “

Valle didn’t testify in his defense, and so he never had the chance to look the members of the jury in the eyes and tell them he’s a freak. As a self-proclaimed sexual sadist and a cop who chatted about rape and murder while sitting in his squad car, his testimony would have been too risky—Valle would have been flayed on cross-examination. So Gatto chose to feed the jury more generic facts about her client’s fetish. On Tuesday, she brought Sergey Merenkov to the stand. He’s the webmaster of a site called DarkFetishNet. It’s like an evil clone of Facebook—a social network where most of the profile pics show a woman being choked or strangled. Valle’s handle on the site was “GirlMeatHunter.”

Merenkov testified via video link from Moscow, a trim, balding 34-year-old in a black T-shirt, sitting in a leather swivel chair and sipping from an “I [heart] TEA” mug. Sexual asphyxiation is the main fetish among his site’s 4,500 active users, he explained, but cannibalism is also popular. He leaned back and gripped the chair behind his head with both hands. The site has tens of thousands of images, mostly pornographic, he continued, and these include “an ever-increasing flood of photos” of private individuals, pulled from Facebook, Flickr, or other sharing sites. Valle uploaded some of these to the site’s “What Would You Do to Her” forums.

Then Gatto calls her paralegal to the stand. A recent graduate from Barnard College, Alexandra Katz looks just like one of the girls that Valle dreamed of cooking and eating. (All of Valle’s alleged victims resemble his wife: They’re petite brunettes with long, straight hair.) To help with the defense, Katz created an account on DarkFetishNet. She visited the site “50 to 100 times,” she says, and now she’s testifying as to how the site actually works. Gatto’s message seems to be: Even this sweet-faced college co-ed visited the site, and she’s totally OK!

It’s not clear how well the gambit works. Katz has a tendency to grin while on the stand, and she ends up seeming smug, not innocent. Still, she gives a sense of how members of the community interact. After setting up her profile, Katz received several dozen private messages. One user called “I Eat” wrote to her with the diction of a Muppet: “Would you like talk with cannibal?” he asked. She declined.

This is Valle’s world, the defense will argue in its closing. All he ever really did was “talk with cannibal,” and then “talk with cannibal” some more. Valle and his friends made plans to kidnap and eat women in online chats, but when the target dates that they had agreed upon arrived, nothing ever happened. Despite the details of his negotiations, Valle never met his DarkFetishNet friend from Asia in a Pakistan hotel, never had a Labor Day rendezvous with his British co-conspirator, and never drove a girl to New Jersey in exchange for $4,000. And no one who was involved in these “conspiracies” ever lamented the fact that these plans hadn’t come to fruition. They just kept on bantering as they had before.

In the final hour of the trial, the prosecutors assure the jury that the First Amendment is not at issue here. What Valle did “goes a thousand steps beyond yelling ‘fire’ in a crowded theater,” Jackson says. “His fantasies point to actual desires.” The closing statement takes a turn, and Jackson works himself into an eloquent lather of prudery and indignation. First he likens the defendant to a 9/11-style plotter who later claimed that he only fantasized about taking down a plane. Then he starts to argue that Valle’s fantasies weren’t sexual at all. “There’s no fun” in what Valle was doing, Jackson says. There’s no pleasure in it for him or you or me.

Jackson reminds the jury that Valle looked at autopsy photos, and pictures of naked girls on spits. According to the prosecution, these images “have no sexual value” at all. “This is not normal pornography for any human being,” he says. And as he did in his opening argument, Jackson reminds the members of the jury to use their “common sense.” Finally, he tells them what’s been at issue in the case from the very start. Gilberto Valle fantasizes about seeing women executed, Jackson announces to the court. “That’s not a fantasy that’s OK.”