Update, March 12, 2013: After deliberating for 16 hours, the jury found Gilberto Valle guilty of both conspiracy to kidnap several women and unauthorized access of a government database. He will be sentenced on June 19.

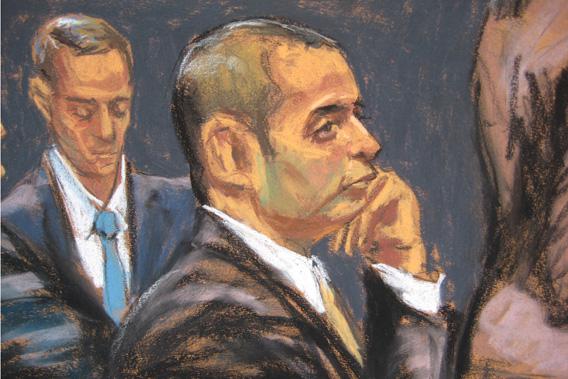

NEW YORK CITY—The Cannibal Cop sits in court, chubby-cheeked, with his chin in the palm of his hand. Though he faces life in prison if convicted—he’s been charged with “a heinous plot to kidnap, rape, murder and cannibalize a number of very real women”—the former New York City police officer barely says a word. Gilberto Valle slouches forward in his seat and holds that pose for hours, while the details of his sexual sadism—plans to cook his friends alive and worse—are read off and posted to a monitor beside him. If this embarrasses Valle, we wouldn’t know. If it angers him, it’s hard to tell. If he’s terrified, he doesn’t show it. He just sits there in the courtroom. He doesn’t do anything at all.

Then again, it’s hard to say exactly what Valle is accused of doing in the first place. He never kidnapped anyone, or raped anyone, or murdered anyone. He was never violent to the women who will take the stand. He’s never tasted human flesh. But he thought about these things, and he talked about these things. He may have even taken steps to plan them out. But did he really mean to do them? “This case is about seeing the difference between the real world and the pretend world on the Internet,” said his lawyer Julia Gatto, a public defender who represented the Times Square bomber Faisal Shahzad, in her opening statement Monday. (Shahzad ended up pleading guilty and getting a life sentence.) “This is a really, really important case. Not for Gilberto Valle, for all of us.”

The lead prosecutor for the government is Randall Jackson, who with his hulking frame and shaved head looks a bit like Tiki Barber. Jackson wants to emphasize that while Valle’s online chats may have started off as fantasy—“depraved, but not true,” is how he put it—they quickly turned into “detailed, strategic discussions about real women.” That is to say, at some point in 2012, Valle crossed the line between masturbatory banter and criminal intent. What he thought and what he typed online bled over into what he planned to do.

The case against Valle begins with testimony from his wife Kathleen Mangan-Valle. Before she tells her story, the judge pauses to remind her of the spousal testimonial privilege: She cannot be compelled to testify against her husband. She waives this right, and then some: Over the next few hours, the former special-ed teacher in Harlem and the Bronx explains how her relationship with Valle, whom she met on OKCupid in 2009, soured not long after they had a child together in 2011. It soured further when she learned that he was trying to kill her.

Something happened in the basement of their home, she begins to say, but the judge prevents her from giving details. Same goes for an exchange they had about a piece of luggage, and some questions that he asked about the route she took while jogging. (Were there a lot of people around on her route? Perhaps she’d prefer to run at night?) Another kind of spousal privilege limits her testimony: According to a rule of law that dates back at least four centuries, what Valle said to his wife in private cannot be used against him (unless the couple had been conspiring together to commit a crime). So the government must stick to what Mangan-Valle saw her husband do, not what she heard him say (to her, at least). Meanwhile, the case against her husband relies on what he said but didn’t do.

Here’s what Mangan-Valle knows: In August 2012, she logged into his account on their shared computer—they share passwords, too—and found some photos from a website called darkfetishnet.com. “I know S&M is kind of popular,” she says, “like 50 Shades of Grey. But this seemed different. The girl on the front page was dead.” At around this point the lawyers huddle with the judge to discuss a legal matter, and Mangan-Valle begins to sob into her microphone. The quiet courtroom fills with the sound of her sobs piped and amplified through loudspeakers.

After a short break, Mangan-Valle tells the court that she installed spyware on her husband’s account, and discovered that he’d been visiting “all these websites that I had never seen before. … There were pictures of feet. They were not attached to bodies.” She took their baby and fled to her parents’ house in Nevada, where she looked deeper into his online activities—she also had the password for his email—and discovered that he’d traded thousands of sadistic emails with online friends. (These were admissible as evidence, because he wasn’t communicating with her.) She searched for her own name, as one might do, and saw that he’d been sending pictures of her to these fetish pals, and that he’d outlined a plan to tie her feet and slit her throat, so that he and his friends could “have fun watching the blood rush out.” That’s when she took the case to the FBI office in Reno, Nev. At her invitation, agents in New York City raided her apartment while Valle was at work, and made a copy of his hard drive.

What, exactly, was in those emails from his account? On Tuesday, FBI special agent Corey Walsh takes the stand. He’s an Iraq War veteran and a central-casting G-Man with short chestnut hair parted neatly on one side. At the prosecutors’ instruction he begins the endless process of reading out the lurid online chats that he and his colleagues discovered in their investigation. The first set describes a bargain struck between Valle and a co-defendant from New Jersey named Michael Van Hise. In those discussions, Valle claims to be an aspiring professional kidnapper, and they work out a deal in which Valle will deliver one of his friends—a real woman he knows—as a sex slave for Van Hise. The two discuss Van Hise’s plans for this victim and how Van Hise intends to rape her right away and then keep her locked up in his house.

Eventually they agree on a price of $4,000 for the kidnapping. Valle promises to drive her over in the trunk of his car one day in February 2012, but when the appointed day arrives, no delivery occurs. The government offers no evidence that Valle and Van Hise discussed this aborted plan again. Instead, the correspondence jumps ahead to another round of negotiations, very similar to the first, except the price is now $5,000. Van Hise never mentions that the price went up, nor that he failed to receive his sex slave the first time around. The two men inexplicably behave as if the first arrangement never even happened.

But this oversight is only inexplicable if you think their plot was real, as opposed to a fantasy role-play that could be varied and repeated from one month to the next. As I pointed out in a preview of the trial a few weeks ago, Van Hise’s own wife knows about his sadistic role-plays and says that she is not particularly afraid of them. In January, she told the New York Daily News, “It’s disturbing, yeah. But you have to accept your partner’s flaws in a marriage.” He’s a “big teddy bear,” she said, and “as hard-core as a baby.” [Update, March 1: The couple does appear to have had some problems in the past. In court on Thursday, prosecutors asserted to the judge (but not the jury) that Van Hise’s wife had kicked him out of the house at one point for “misconduct with her children.”]

The next set of Valle’s correspondences—the next of his murderous plots—to be read aloud involved a different co-conspirator: An as-yet-unidentified Brit known online as “Moody Blues” or “MeatMarketMan.” [Update, March 1: British newspapers are now reporting that Moody Blues was arrested on Feb. 21 for child pornography. He is allegedly a 57-year-old male nurse from Canterbury named Dale Bolinger.] Unlike Valle or Van Hise, whose online communications tend toward the addle-headed brevity of the compulsive masturbator—simple phrases and ideas, urgently repeated—the messages from Moody Blues are those of a filthy aesthete. He lingers on the details of his fetish with dry precision, presenting himself as a master cannibal with years of experience. “I’m considering going for a Filipino over here,” he says at one point. “Any port in a storm, as it were.”

As Special Agent Walsh reads through the chats and emails, one imagines Moody Blues as a toothy gent in a windowpane blazer, typing away at his computer as he puffs on a long-stemmed Briar pipe. “I enjoy it all, even the offal,” he declares. “Nothing like stuffed heart!” He proposes detaching their victim’s hands, cupping them around a gowpenful of rice and chilis, and steaming them up for a nice supper. Then he mentions that he has a recipe for haggis using the lungs and heart, and one for black pudding made from breast fat and blood. At times Moody Blues seems to be slipping into a wholesale Hannibal Lecter impersonation: Before it’s done, I’m ready for him to suggest sautéing up her liver with some fava beans and a nice Chianti.

Valle’s plot with Moody Blues to kidnap and eat his college friend Kimberly devolves into obsessive recaps of their absurd arrangement. He pretends to have a secluded mountain retreat where the pair could roast Kimberly with impunity in an open-air barbecue. According to their arrangement, the Brit will hop across the pond for Labor Day, so he and Valle can go to Home Depot for supplies and spend a day or two constructing their human rotisserie. It sounds like they’re planning for a weekend bro-down.

Other passages read like twisted cybersex, as two ostensibly heterosexual men get each other off in an online chat. They talk dirty about desires so violent and so insane that they could never be realized in real life. The loneliness of this predicament seems to play out in a weird and painful intimacy, and an aching need to push deeper and deeper into shared fantasy. When Valle creates a file on his computer called “Abducting and Cooking Kimberly: A Blueprint”—a key exhibit in the government’s case—he emails it to Moody Blues. This is not a highly technical document: Below “materials needed,” Valle puts down “sneakers,” “gloves” and “a car (have it).” Rather, it might be a prop shared across a circle jerk.

The FBI sorted Valle’s emails into two piles, says Walsh: Some were self-described fantasies, but the others—the ones at issue in the trial—involved real plans to kidnap and eat real women. How did the agents know which were real? For one, Valle and his “co-conspirators” repeatedly describe their plans as such. “Just a point of reference,” Valle tells Van Hise at one point. “A good custom-made video goes for $1,500 … you’re getting the real deal.” Later he says, “She will definitely make the news.”

With Moody Blues, the claims of authenticity are even more explicit. They discuss the added pleasure of knowing that their human meat will be “real.” Moody Blues, playing the role of expert, advises Valle on safety issues and otherwise prods him to make their plot more realistic. When Valle cartoonishly proposes that they might silence their victim with an apple—a common trope in cannibal porn—his partner corrects him: “No, you need to use a gag.” “Good point,” says Valle. “You WILL go through with this?” asks Moody Blues, and then: “I’ve been let down before.”

What does all this mean? The government argues that Valle’s fantasies were real, and that we know they’re real because Valle and his friends said so, over and over again. The defense will argue the opposite: Claiming that the fantasies are real is central to the fantasies themselves; a role-play transpires in layers of fantasy talk, and then fantasy talk about that talk.

The government has more tangible evidence, too. Valle seems to have entered his intended victims’ names into a police database and otherwise tried to learn their home addresses. He also met with several of these women in person during 2012. These might be the “overt acts” in furtherance of his conspiracy that must be proved to gain a conviction, but so far, at least, the acts seem innocuous. Yes, Valle did meet Kimberly for brunch at Cafe Deluxe in Gaithersburg, Md., last year. But he brought along his wife and baby, and Kimberly herself noticed nothing strange about the encounter. Yes, he visited his high-school friend Maureen at work in Midtown one day, but he came by in a patrol car with a fellow cop. She also testified that she did not feel threatened by this behavior.

Yet it’s also true that in the lead-up to these encounters with his female friends, Valle chatted online about murdering the same friends. The week before his brunch with Kimberly, he promised Moody Blues that he would size her up as a tasty morsel. (“Don’t be TOO obvious,” cautioned the Brit. “Drooling is definitely out!”) So what does Valle really think of all these women, whether he meant to kill them or not? Is he a psychopath who cares nothing for his wife or for his friends—who maybe even hates them—and who spent years conning them with intimacy so that he could abuse them in his sexual fantasies? Or does Valle love these women even as he dreams of their murder? Are they fodder for his plots only because he knows them, and because the details of that knowledge make his fantasies more exciting?

As the trial continues, the jury will be asked to figure out the difference between the real world and the pretend world inside of Gilberto Valle’s head. The problem is that his head is not like theirs, or yours or mine. In his opening statement, prosecutor Randall Jackson told the jurors to “use your common sense” in making this distinction, but I’m not sure that common sense will help. What use is intuition when you’re hearing from a man who fantasized about eating human haggis? When Jackson says to “use your common sense,” is he making a coded invitation for the jurors to punish Valle’s uncommon desires?

Next week, Valle is expected to testify in his own defense. For the first time, he’ll have the chance to say what he really thinks and help the jury to understand where his fantasies were going.