A System Designed to Make People Disappear

I tried to represent an undocumented man rounded up by ICE. I couldn’t even find him.

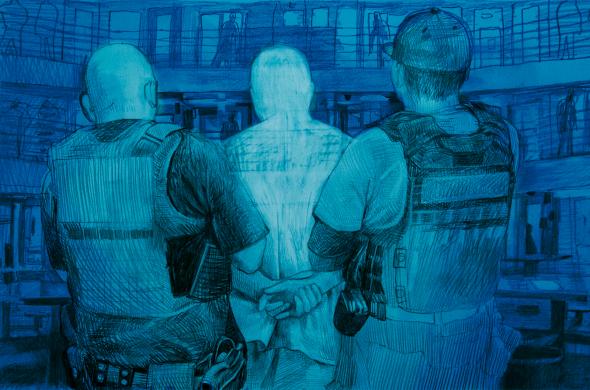

Lisa Larson-Walker

A couple of weeks ago, for the first time ever, I represented an undocumented worker in deportation proceedings. Or rather, I tried to. My attempts to navigate this system were not what I would call successful. Part of this may be due to the fact that, though I have been a practicing attorney for 10 years, this was my first go at immigration law. But another part of it—most of it, I’d venture—is due to the fact that the U.S. immigration system is designed to be opaque, confusing, and inequitable.

Under most circumstances, I would not wade into this kind of thing at all. I’m primarily a civil rights lawyer, and immigration is a highly specialized area of law with a unique set of risks awaiting unwary practitioners. I would not, for example, take someone’s bankruptcy case or file adoption papers. I would refer those to lawyers with experience in those areas. But the crisis of unrepresented detainees is too big and too pressing to leave to the few organizations and individual practitioners with expertise in immigration law. One recent study found that only about 14 percent of detainees have representation. That’s out of nearly 300,000 cases in the immigration courts every year.*

If I killed someone on the street in broad daylight, I‘d be entitled to an attorney. But those summoned before the immigration courts, including infants who have been brought here by their parents, have no right to counsel. They can hire immigration lawyers, but only if they can pay for them. Most of them can’t, and volunteer lawyers are scarce. So children, parents, and grandparents are locked up for months, sometimes years, waiting for a day in court. When they show up in front of a judge, they do so alone and terrified. Those who don’t speak English are provided an interpreter who tells them what’s being said, but no one is there to tell them what’s really happening.

Undocumented people who live here in Louisville and southern Indiana are driven 90 minutes to the jail in Boone County, Kentucky. There, they are placed in the general population with locals who have actually been accused of crimes. That’s where my client, who was assigned to me by an overburdened immigration firm, was taken after he was scooped up by Immigration and Customs Enforcement in the parking lot of his apartment building.

Entering the United States, even without proper documentation, is a federal misdemeanor. But in my view, the only “crime” my client committed is trying to get his family away from the drug cartels that overtook his Central American village.* Unlike many who come here fleeing crippling poverty, he and his family were getting along fairly well in their home country. A little success, it turns out, can make you a target for violent extortionists. His wife, who fled the exact same situation in the exact same place, was apparently catalogued as an asylum-seeker, but her husband was not.

The Kentucky facility doesn’t allow a phone call, even for an attorney, without an appointment. Requests to call your client must be made by fax. Sometimes the jail will call you to say your 2 p.m. time slot has been changed to 6 p.m., and sometimes you won’t get any notification at all. The visitation restrictions for families are no more accommodating. Visitation amounts to 45 minutes a week, tops. If my client’s wife, daughter, or grandkids want to visit him, they have to drive 90 minutes and hope for the best.

My first step was to figure out if my client was eligible for bond; if I could get him out of detention, he could return to his full-time job and support his family rather than sit in jail for months waiting on a hearing. Since time was of the essence, I started drafting a bond motion without knowing whether he was eligible or not. My firm got the necessary materials together: letters from his wife, employer, and pastor; his car title; his lease; information about the extreme violence and corruption he’d escaped. Given that he’d told ICE about the situation in his home country, he should’ve been entitled to what’s called a “reasonable fear” interview and maybe—just maybe—been allowed to stay in the country. But I didn’t know if such an interview had been scheduled. Neither did my client.

The only way to determine his eligibility for bond, or whether he would be granted that interview, was to talk to an ICE agent.* ICE, though, won’t talk to you without a form signed by the client. We faxed the form to the jail; it was never returned, and the ICE agents wouldn’t return my repeated calls. Meanwhile, I tried to figure out where the bond motion should be filed, because in this nonsense world you can file in the immigration court in Memphis (five hours from the client) or Chicago (six hours away) or somewhere else.

All the while, I was trying to get sworn in to practice immigration cases. A bureaucrat in Memphis told me I should go to the court in Louisville on a certain date. When I showed up on that date, the court was closed and the building shuttered. My assistant called Memphis for a new appointment. This time, a different bureaucrat said he needed more information from me—that I couldn’t just show up in court. What kind of information? He wouldn’t say. When I called back, the bureaucrat was gone, apparently forever. He never called me back. I later found out that you can, in fact, go to the court to get sworn in at any time.

I faxed another request to speak to my client about getting the form returned. This time, I was told that he was no longer in the Kentucky jail. Where was he? They didn’t know.

For a short time, I operated under the assumption that my client had been shipped to Chicago, which is where the Department of Homeland Security sends just about everyone from Kentucky. I called Chicago. A creepy robot answered the phone. I left a message, because that’s all I could do. Then he showed up in the computer as having been moved to Kenosha, Wisconsin. Why? No one knows. At that point he had been locked up for a month.

Attorneys aren’t permitted to call the Wisconsin facility; the detainee must call collect at a designated time. They didn’t tell me when that would be. If it was unfeasible for his relatives to visit before, it was impossible now. They might as well have moved him to the moon.

As I didn’t know when the calls were going to happen, I couldn’t guarantee I’d have an interpreter on hand every time I talked to him. I was often left to rely on my college Spanish, which would have been enough if I were trying to talk about the weather or make a hotel reservation. But when it came to explaining legal concepts I barely understand in English, or expressing basic human empathy, I came up short.

Almost two weeks after being shipped to Wisconsin, my client disappeared from both the Kenosha facility and the database that tracks detainee whereabouts. The family, concerned about the myriad health problems he’s experienced since his detention, wanted to know if he was dead. I didn’t know. Eventually, one of the family’s advocates from their church got a one-line email from a bureaucrat in Chicago. He’d been moved to “Alexandria,” which, as it turns out, is in Louisiana. Why? No one could say. If we could get ahold of the facility in Louisiana, maybe we could find out. But no one knew quite how to do that, including dedicated immigration attorneys on the ground in Louisiana.

It is not uncommon for detainees in this situation, after months of being surreptitiously shuttled all over the country, to sign voluntary deportation orders. It’s a way to exert some control over a situation that is heinously inexplicable, even for an English-speaking lawyer who grew up in America. Locking up accused criminals indefinitely is a tried-and-true way of getting them to plead guilty, whether they actually committed a crime or not. The same principle applies to immigration detainees. And criminal defendants, even those accused of the worst crimes imaginable, don’t get sent to three different states in a two-month period as part of their pretrial detention.

At long last, my client was allowed to make a tearful, five-minute collect call to his wife, in which he confirmed that he was alive and that he would be deported the next day. I can’t say with absolute certainty whether he ever actually signed a voluntary deportation order. No one, including my client, seems to know for sure. If ICE knows, it isn’t telling. All I know is that he made it back to his home country and is safe, for now.

I’m sure I could have done some things differently in this case. But I had good advisers every step of the way, and I have never been afraid to ask even the most basic questions. The problem is that many of those questions had no real answers. Would I have been better off with years of experience navigating the system? Definitely. Would that experience have made any practical difference for my client? Probably not. Even the most seasoned practitioners recognize that the system is designed to deprive people of representation, due process, and humanity itself.

What happened to my client and his family wasn’t anomalous. It wasn’t even unusual. It happens all over the country, every single day. Part of what makes our immigration system so reprehensible is that it’s so easy to ignore. Most of us don’t ever have to deal with it in any meaningful way or even think about it. But stop and consider that this practice of moving detainees from place to place randomly, with no notice given to their families or their attorneys, is indescribably cruel. Stop and consider that locking up human beings in jail for months to coerce them into submission is maddeningly unjust. And then consider the possibility that the whole system is not just dysfunctional, but utterly diabolical.

Further consider that the practice of breaking up families and making people disappear into black holes is the result of a set of loosely defined policy goals that are in no way based on reality. There’s no real evidence to support the notion that undocumented immigrants are any more dangerous than anyone else, or that they “steal” jobs from Americans, or that they do anything but contribute to the economy overall. There is no policy reason for inflicting this misery on people. It’s just cruel.

Lest anyone think this is just more liberal railing against the Trump administration, this system pre-dates the orange guy. The Obama administration sucked more than three million people into the lungs of this administrative monster and spit them out all over the world. Having seen up close what this system does to families, it’s hard to forgive that, especially when you consider that American trade policies contributed to the collapse of Latin America. But hell, we’re all complicit in this. We let it happen every day.

I’m going to suggest something I have never suggested to any working person: If you are part of this machine—if you are a guard, an agent, a janitor, or anything in between—quit. Walk off your job. Right now. You’ve got bills to pay? A family to support? I get it. So do the people who come here looking for a better existence. The system you are contributing to is preposterously evil. It separates mothers from their children. It kills innocent people. It exists only to make easy punching bags out of those damned by their circumstances, some of whom have already lived through unspeakable horrors.

For everyone else: If you’ve never thought about your tacit support for this system, start thinking about it. Start resisting it. Start demanding its abolition. A Kafkaesque bureaucracy needs participants, both willing and unwilling. We have the power to dismantle it.

Correction, April 3, 2017: Due to a production error, this article originally stated that 1 out of nearly 300,000 immigration cases involved detainees with legal representation. Fourteen percent of cases do. This piece also incorrectly stated that entering the United States without proper documentation is not a criminal offense. It is a federal misdemeanor. Additionally, this piece incorrectly stated that a person who’s granted a “reasonable fear” interview may be eligible for asylum. Passing such an interview would typically allow someone to apply for “withholding of removal” from the United States.