Following is an excerpt from Matt Taibbi’s introduction to the 40th anniversary edition of Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, out now from Simon & Schuster.

I doubt any book means more to a single professional sect than Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 means to American political journalists. It’s been read and reread by practically every living reporter in this country, and just as you’re likely to find a dog-eared paperback copy of Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop somewhere in every foreign correspondent’s backpack, you can still spot the familiar red (it was red back then) cover of Fear and Loathing ’72 poking out of the duffel bags of the reporters sent to follow the likes of Mitt Romney, Rick Santorum, and Barack Obama on the journalistic Siberia known as the Campaign Trail.

Decades after it was written, in fact, Fear and Loathing ’72 is still considered a kind of bible of political reporting. It’s given birth to a whole generation of clichés and literary memes, with many campaign reporters (including, unfortunately, me) finding themselves consciously or unconsciously making villainous Nixons, or Quislingian Muskies, or Christlike McGoverns out of each new quadrennial batch of presidential pretenders.

Even the process itself has evolved to keep pace with the narrative expectations for the campaign story we all have now because of Hunter and Fear and Loathing. The scenes in this book where Hunter shoots zingers at beered-up McGovern staffers at places like “a party on the roof of the Doral” might have just been stylized asides in the book, but on the real Campaign Trail they’ve become formalized parts of the messaging process, where both reporters and candidates constantly use these Thompsonian backdrops as vehicles to move their respective products.

Every campaign seems to have a hotshot reporter and a campaign manager who recreate and replay the roles of Hunter and Frank Mankiewicz (Karl Rove has played the part a few times), and if this or that campaign’s staffers don’t come down to the hotel bar often enough for the chummy late-night off-the-record bull sessions that became campaign legend because of this book, reporters will actually complain out loud, like the failure to follow the script is a character flaw of the candidate.

Some of this seems trite and clichéd now, but at the time, telling the world about all of these behind-the-scenes rituals was groundbreaking stuff. That this is a great piece of documentary journalism about how American politics works is beyond question—for as long as people are interested in the topic, this will be one of the first places people look to find out what our electoral process looks like and smells like and sounds like, off-camera. Thompson caught countless nuances of that particular race that probably eluded the rest of the established reporters. It shines through in the book that he was not merely interested in the 1972 campaign but obsessed by it, and he followed the minutiae of it with an addict’s tenacity.

For instance, there’s a scene early in the book when he confronts McGovern’s New Hampshire campaign manager, Joe Granmaison, badgering the portly pol about having been a Johnson delegate in 1968:

“Let’s talk about that word accountable,” I said. “I get the feeling you stepped in shit on that one.”

“What do you mean?” he snapped. “Just because I was a Johnson delegate doesn’t mean anything. I’m not running for anything.”

“Good,” I said.

Now, not many reporters would bother to find out what a lowly regional manager for a primary long-shot candidate was doing four years ago, but Hunter had to know. The whole book reeked of a kind of desperation to know where absolutely everyone he met stood on the manic quest to find meaning and redemption that was his campaign adventure.

The obsession made for great theater, but it also produced great journalism. Hunter knew the geography of the 1972 campaign the way a stalker knows a starlet’s travel routine, and when he put it all down on paper, it was lit up with the kind of wildly vivid detail that only a genuinely crazy person, all mixed up with rage and misplaced love, can bring to a subject.

But saying Campaign Trail ’72 is a good source on presidential campaigns is almost like saying Moby-Dick is a good book about whales. This is more than a nonfiction title that’s narrowly about modern American elections. If it were only that, it wouldn’t endure the way it has or resonate so powerfully the way it still does.

Hunter had such a brilliantly flashy narrative style that a lot of people were fooled into thinking that’s all he was—a wacky, drug-addled literary party animal with a gift for memorable insults and profanity-laden one-liners. The people who understood him the least (and a lot of these sorry individuals came out of the woodwork, bleating their complaints on right-wing talk shows and websites, when Thompson died) had this idea that he was just the journalistic version of a rock star, an abject hedonist with a gift for the catchy tune who was popular with kids because he stood for Letting Loose and Getting Off without consequence. I particularly remember this passage from someone named Austin Ruse in the National Review:

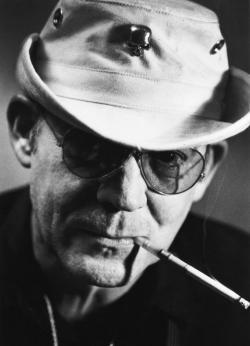

Author Hunter S. Thompson.

Photo by William J. Dibble.

[Thompson’s] famous aphorism, “When the going gets tough, the weird turn pro” was the font of more ruined GPAs than any other single source back in the 1970s. “When the going gets tough, the weird turn pro” meant that you could stay up all night doing every manner of substance and in the few milky hours between sunrise and the start of morning classes churn out a master term paper. Almost all of us discovered this was not true. Some, like Hunter himself, never learned it.

People like this either never read Hunter’s books, or they read them and didn’t understand them at all. All the drugs and the wildness and the profanity … I’m not going to say it was an act, because as far as I know it was all very real, but they weren’t central to what made his books work.

People all over the world don’t identify with Hunter Thompson because he was some kind of all-world fraternity-party God who made a sexy living mainlining human adrenal fluids and spray-painting obscenities on the sides of racing yachts. No, they connect with the deathly earnest, passionate, troubled person underneath, the one who was so bothered by the various unanswerable issues of life that he went overboard trying to medicate the questions away.

People who describe Thompson’s dark and profane jokes as “cynical humor” don’t get it. Hunter Thompson was always the polar opposite of a cynic. A cynic, in the landscape of Campaign Trail ’72, for instance, is someone like Nixon or Ed Muskie, someone who cheerfully accepts the fundamental dishonesty of the American political process and is able to calmly deal with it on those terms, without horror.

But Thompson couldn’t accept any of it. This book buzzes throughout with genuine surprise and outrage that people could swallow wholesale bogus marketing formulations like “the ideal centrist candidate,” or could pull a lever for Nixon, a “Barbie-Doll president, with his box-full of Barbie Doll children.” Even at the very end of the book, when McGovern’s cause was so obviously lost, Thompson’s hope and belief still far outweighed his rational calculation, as he predicted a mere 5.5 percent margin of victory for the Evil One (it turned out to be a 23 percent landslide for Nixon).

When I read this book now, it reminds me a lot more of vast comic epics like The Castle or The Trial than one of Fear and Loathing’s smart nonfiction thematic contemporaries (like the excellent The Selling of the President, 1968, for instance). Just like Kafka’s Land Surveyor, Hunter in Campaign Trail ’72 enters a nightmarish maze of deceptions and prevarications and proceeds to throw open every door—bursting into every room with a circus clown’s theatrical self-importance and impeccably bad timing—searching every nook and cranny for the great Answer, for Justice.

What makes the story so painful, and so painfully funny, is that Hunter chooses the presidential campaign, of all places, to conduct this hopeless search for truth and justice. It’s probably worse now than it was in Hunter’s day, but the American presidential campaign is the last place in the world a sane man would go in search of anything like honesty. It may be the most fake place on earth.

Both now and in Thompson’s day, most of the press figures we lionize as great pundits and commentators seem to think it’s proper to mute our expectations for public figures. We’re constantly told that politicians should be given credit for being “realistic” (in the mouths of people like David Brooks, “realistic” is really code for “being willing to sell out your constituents in order to get elected”) and that demanding “purity” from our leaders is somehow immature (Hillary had to vote for the Iraq war; otherwise she would have ruined her presidential chances!).

To me, the reason so many pundits and politicians take this stance is because the alternative is so painful: If you cling to hope and belief, the distance between the ideal and the corrupt reality is so great, it’s just too much for most normal people to handle. So they make peace with the lie, rather than drive themselves crazy worrying about how insanely horrible and ridiculous things really are.

But Thompson never made that calculation. He never stooped to trying to sell us on stupidities about “electability” and “realism,” or the pitfalls of “purity.” Instead, he stared right into the flaming-hot sun of shameless lies and cynical horseshit that is our politics, and he described exactly what he saw—probably at serious cost to his own mental health, but the benefit to us was Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72.

We can easily imagine how Hunter would have described people like Mitt Romney (I’m guessing he would have reached for “depraved scumsucking whore” pretty early in his coverage) and Rick Santorum (“screeching rectum-faced celibate”?), and all you have to do is look at his write-up of the Eagleton affair to see how this writer would have responded to whatever manufactured noncontroversy of the Bill Ayers/Reverend Wright genus ends up rocking the 2012 election season.

But more than anything, this book remains fresh because Thompson’s writing style hasn’t aged a single day since 1972. Thompson didn’t write in the language of the sixties and seventies—he created his own timelessly weird language that seems as original now as I imagine it did back then. When you read his stuff even today, the “Man, where the hell did he come up with that image?” factor is just as high as it ever was. There’s a section in this book where he’s fantasizing about the pro- Vietnam labor leader George Meany’s reaction to McGovern’s nomination:

He raged incoherently at the Tube for eight minutes without drawing a breath, then suddenly his face turned beet red and his head swelled up to twice its normal size. Seconds later—while his henchmen looked on in mute horror—Meany swallowed his tongue, rolled out the door like a log, and crawled through a plate glass window.

I’ve read every one of Thompson’s books three or four times, and I’ve probably read hundreds of passages like this, but this stuff still makes me laugh out loud. Why a plate glass window exactly? Where did he come up with that? On top of everything else, on top of all the passion and the illuminating outrage and the great journalism, the guy was just one of a kind as a writer. Nobody was ever more fun to read. He’s the best there ever was, and still the best there is.

Excerpted from Matt Taibbi’s introduction to the 40th anniversary edition of Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, out now from Simon & Schuster. Copyright 2012 by Matt Taibbi.